“Get up,” Scott George tells his people, the Osage, in the original song that concludes “Killers of the Flower Moon.” “God, Wakonda, made it this way for us,” he sings in the Osage language.

It is a short and simple message, but underneath flows a deep river of history and tradition.

The deeper meaning, George says, “is that I want our people to stand up and recognize the fact that it is God's way: He has brought us here. And you can reference everything we've been through, everything that happened to us as a people, and here we are… we're still here.”

Discussing his first Academy Award nomination, for the song “Wahzhazhe (A Song for My People),” George answers a Zoom call from Shawnee, Oklahoma, where he just met with a team from the University of Oklahoma about implementing geothermal energy in the affordable housing program he leads for the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. In other words: Scott George is not your typical Hollywood composer.

He grew up in the town of Hominy in Osage County, not far from where Martin Scorsese filmed most of “Flower Moon.” Based on David Grann's 2017 novel, the film turned to Osage support and guidance to authenticate their horrific true story about the murder epidemic that plagued their recent ancestors in Oklahoma in the 1920s.

George, who now lives in Oklahoma City, is also the lead singer of the group Osage Veterans Soldier Dance. He heard about Scorsese's production and met people who were trying out for roles, and was a little cautious. Specifically, he was concerned that his group would be asked to perform a ceremonial dance in the film.

“We don't allow them to be filmed,” he says, “and we don't welcome being filmed. So that was a no-go situation for us, and we kind of held back and didn't volunteer for anything at that time.”

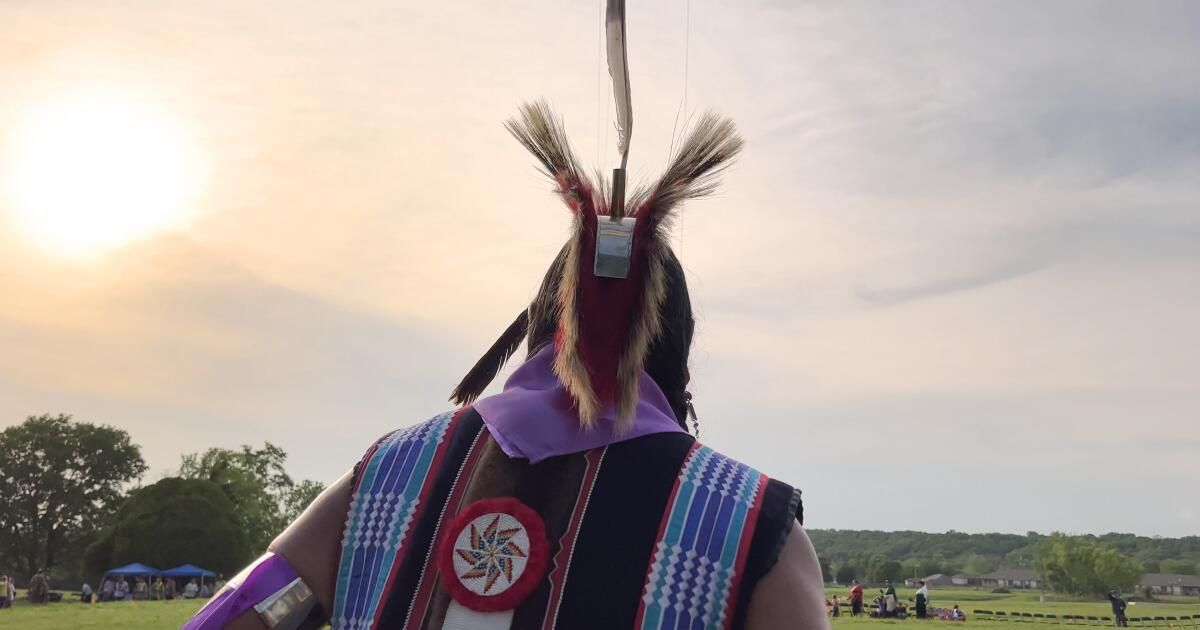

Composer Scott George wrote “Wahzhazhe (A Song for My People),” the Oscar-nominated closing song for “Killers of the Flower Moon,” after initially not wanting to participate in the film.

(Dan Steinberg/Dan Steinberg)

Then Scorsese and the film's stars, Lily Gladstone and Leonardo DiCaprio, began attending the ceremonies, and George was surprised by how attentive they were.

“Be prepared,” he told a friend, “because chances are they will tell us something or ask us to do something.”

Sure enough, he received a call from Vann Bighorse, director of the Osage language department of the Osage Nation, who had been advising Scorsese and the late Robbie Robertson, composer of the film's soundtrack. Bighorse and his brother, Kenneth Bighorse Jr., have sung with George for years, and the three men met to discuss Scorsese's request that they perform a traditional dance for the film's final scene.

George's suspicions were confirmed “in the sense that they wanted what they saw in our ceremonial, they wanted the energy and all that,” he says. “It took us a while to come to the conclusion that we just needed to make our own song.”

The main reason: respect. The group's repertoire consists mainly of songs dating from 200 to 400 years ago and invoking the names of the actual relatives and ancestors of living peoples. Additionally, most of the songs are in the Ponca language, sister to the Osage. “A lot of that music belongs to them,” George says.

A drone takes aerial photographs of the Osage ceremonial dance that closes “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

(Apple Original Movies)

So he set about creating a new song for his people for this story, and the result was “Wahzhazhe (A Song for My People)”.

Rooted in the style and structure of a traditional Southern Plains song (a “throwback,” George says), “Wahzhazhe” was recorded in one day, outdoors, when Scorsese filmed it for its finale. George and his fellow singers and dancers were captured in an aerial shot taken from God's Eye, which begins with a giant drum made of buffalo hide and slowly rises to reveal a strikingly colorful pinwheel of ceremonial garments and movements.

George was invited to sit next to Scorsese in his elevated position between takes and was able to see his group from a completely new perspective, although he didn't really understand it until he saw the scene after the entire movie.

“The movie itself takes you through a lot of emotions,” says George, “especially for us as an Osage people. But when we saw that, I think we understood what he was trying to achieve, to show that this is us now, this is who we are. And from my perspective, he did a good job of doing it.”

The song's message, sung passionately by men and women in simple harmony, is literally directed at the Osage, but George hopes it will spark curiosity and even affection for Native American music among the broader public.

“It's the most powerful thing we do,” he says. “It calls us together and defines who we are. And as far as I can tell, he has been on this continent as long as we have.”