When Denisa Hanna opened the text and saw images of the flames and the fire of the fire of Palisades moving from the highlands, she knew she had to cancel the essay.

He was safe at home, in the middle of the city, but the images had come from the Lutheran Church of Palisades Secretary, which was evacuating. The roads were stuck and the wind howled.

“Please keep safe and say prayers for our friends near this horrible disaster,” Hanna, president of the Palisades Symphony Orchestra, wrote in an email to its members.

They had planned to meet that night in the church in Sunset Boulevard, their first New Year practice. For almost 60 years, the volunteer orchestra, along with Brentwood Palisades Chorale, had served the community with a series of annual programs, and its first 2025 concert was just a few weeks away.

Debbie Rafei embraces his cousin, the symphonic violinist of Palisades, Douglas Green, who lost his home in the fire of Palisades, during the intermediate.

Both unlikely and inspiring, the 70 -members orchestra grew from an incipient adult education program in local high school to a beloved institution through the hard work of its founder, Joel Lish and Eva Holberg. Lish died in 2024 and Holberg two years before, but the symphony was still played.

But now his future had obscured when the embers became flames and llamas ran through the neighborhoods to the sea, and the music they loved remained silent.

The next day, Hanna, who also acts with the orchestra on the bass, sent another email. Although the Lutheran Church Palisades had not caught fire, their community, and the houses of the members were in ashes.

“Due to devastation,” he wrote, “I am not very sure of the trials. We may not even enter the Palisades for quite some time.”

The scope of the disaster was made clear when the orchestra began to connect again.

“We lost our house,” wrote the first violinist Helen Bendix in a brief email to the musical director and director Maxim Kuzin.

The Palisades symphonic violinist, Helen Bendix, on the left, who lost her home in Palisades fire, is congratulated by Lynda Jackson after the symphony performance.

Bendix was one of the 16 members of the symphony and the coral that had lost its homes. Among the fire storms of Palisades and Eaton that week, more than 16,000 structures were lost and at least 29 people killed.

As a result of such a tragedy, the musicians wondered how, even if, they could continue.

Violins and violas had to be saved. On the morning of the fire, Bendix grabbed them and headed with her husband to her car. The instruments were a connection with his mother, who had touched the cello and died in 2020. At 72, Bendix was not about to lose that.

The impulse was as close to an instinct as he had always felt, although he assumed that his home would be safe. There were a portrait of his grandmother, photographs of his family, jewelry, costumes and the less sentimental essential elements of life, glasses to read music, tax records, medications, passports and car.

Seven miles to the west from where Palisades fire began in Temescal Canyon, Ingemar Hulhage did not grab his violin. With the progress of the fire, he and his partner, Melinda Singer, caged their cats, loaded them in the car and moved away from their home without exit to the west of Topanga, with the hope that they would return.

The Palisades Symphony member, Stan Hecht, reaches his hype to the Westwood Methodist Church before the charity.

He didn't think the flames would travel as far as they did. He had lost his home in the 1993 Malibu fire, along with his most precious fagnola violin, but returned and rebuilt, installing a sprinkle system and buying another violin.

Received by a friend in Van Nuys, Hulthage hoped that the story is not repeated. But a video of a neighbor taken a day later confirmed the loss. There had been no water for the sprinklers.

Like hundreds of families in Los Angeles who had lost everything overnight, they live, Hulthage and Bendix soon had losses and sought a place to live, a minimum of stability.

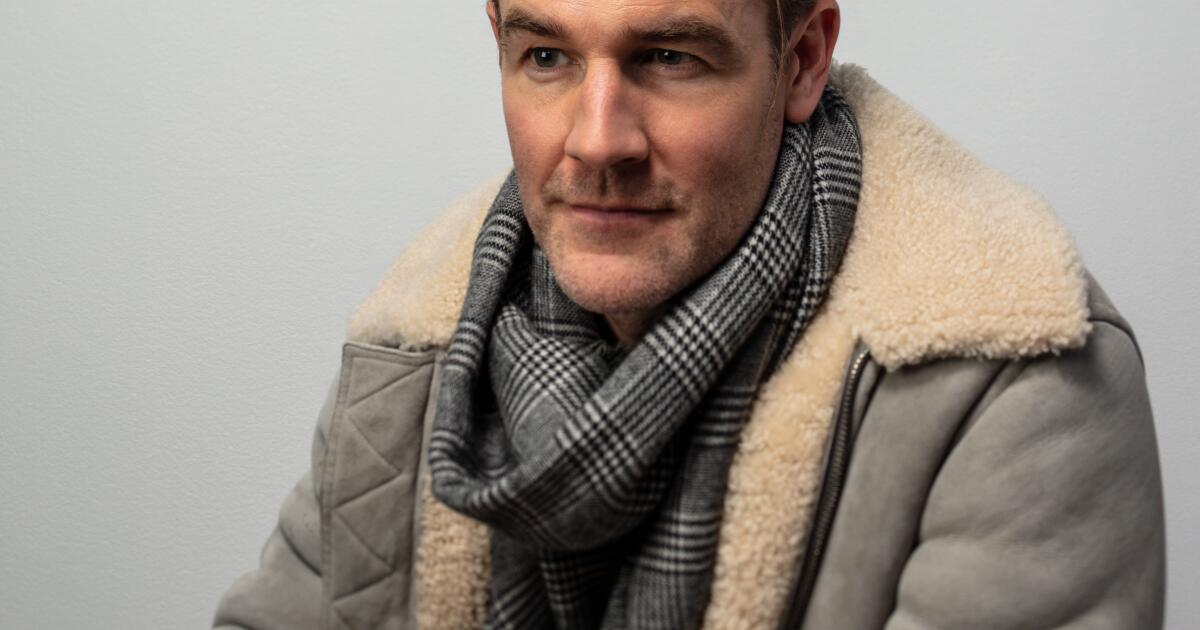

The musical director Maxim Kuzin, Center, and Palisades Symphony recognize the applause after their performance.

When Maxim Kuzin began to receive emails from the orchestra members who asked when the trials would resume, I was not sure how to answer. He had been with the orchestra for only one year and had always felt strength in the dedication of its members.

He lived in Gardena, far from devastation, but knew how disorienting can be the loss. He had emigrated from Ukraine in 2014 when Russia attached to Crimea, but felt that he had never really left. Then, when news arrived last year that his childhood house in kyiv had been beaten by a missile, he was stunned.

Maybe music could help. He thought about the program he had planned in December: the Oberura de Taras Bulba by Mykola Lysenko, an Edvard Grieg concert and César Franck's symphony in D Minor. Perhaps as the musicians who endured the siege of Sarajevo in 1992 and still acted on the front line, they could also shake their fists in the universe, in the forces of chaos and destruction.

“Recognizing the power of music to comfort and heal, we have decided to resume essays as soon as this Tuesday, January 14,” he wrote in an email to the orchestra.

When Bendix read these words, he felt a feeling of relief. Advancing sometimes means not looking back.

“We have to gather,” he replied, waiting for him not too rusty.

The symphonic violinist of Palisades, Ingemar Hulthage, center, who lost his home in the fire of Palisades, moves a piano with the violist David Quinn during the intermediate.

Without his violin, Hulthage wondered if he could even play. He joined the orchestra almost 25 years ago. As a second violin, he considered himself amateur, but he had always felt at home in the company of musicians.

Hanna knew she could help.

Many of the other musicians had saved their instruments. A friend, who played low and owned some electric bass, and who had lost his house, even joked about it. “I have lower in this motel room than underwear,” he said.

Like a luthier, an expert in repairing rope instruments, Hanna had a violin, could give Hultage, and when the orchestra met on January 14 to rehearse in the small meeting room of a life center for older people in Westwood, He presented it. He was defeated.

“This was the most normal thing I've felt from fire,” he said.

Now they had a month to prepare.

Four weeks later, on the day of the concert, Hulthage bought a tuxedo, but he had not yet changed, since he helped establish chairs for the ropes on the cruise of the Methodist Methodist of Westwood. Although its performance space, the Lutheran Church in Pacific Palisades, was still intact, the months of cleaning the soot and riding the smell of smoke were advanced.

The guest soloist Alexander Wasserman practiced Grieg's concert, chords like Thunderclaps that resonate from the tail piano, a beautiful Shigeru Kawai from Black-Lacquer donated for this performance.

Two men fought with three great timbales drums for the steps towards the space before the altar. Another maneuvered the harp to the choir. In the lobby, Katie Rudner folded programs for guests who arrived and delivered envelopes for controls and helped with venmo charges. Donations would be reserved to help musicians and community members.

At 7 PM Bendix arrived, dressed in a black sequin skirt, a jacket, scarf and earrings that his children had presented him after fire. He found his seat in the second row and began to heat the violin that his mother gave him 25 years ago.

Maxim Kuzin carries out the symphony of Palisades. He lived in Gardena, far from the devastation of fire, but knew how disorienting it can be the loss. He had emigrated from Ukraine in 2014 when Russia attached Crimea.

Kuzin, dressed in an embroidered Ukrainian shirt, greeted friends and supporters. More than 200 visitors slowly filled the sanctuary, and at 7:30 Hanna went to the audience, beginning with his gratitude for the use of the Church and closing in appreciation for the many who had helped make possible the night. Then he resigned and walked where his bass was.

Kuzin raised his cane.

With two ascending notes, then two more and two more, the orchestra began the heroic overture of Lysenko, its lyrical greatness emerging slowly when the strings and horns accumulated strength and its impulse soon swelled its exciting nearby.

As the applause decreased, Kuzin took a moment to go to the audience. The piece of the Ukrainian composer, rarely made in the United States, caused the driver's pride.

Attendees applaud the performance of the Palisades symphony.

“I hope they can understand why Ukrainians cannot lose war. A nation with such music cannot simply lose, “he said before welcoming Wasserman, who delivered a dramatic and sweet interpretation of the Grieg concert.

After the intermediate, Kuzin appealed to the audience for his financial support, briefly speaking about the fire and those who lost everything.

“I hope some of us have the idea that we now live in a different world than we all did in this period of time,” he said, hoping to recreate the community with music, a bond of empathy, so that he is a result of From this tragedy, “eventually, hopefully, some kind of meaning will be revealed to those of you who suffered.”

The D-minor key of the Franck Symphony established a gloomy mood when the violins tried And the heat. The crescendos broke as an overwhelming force on musicians and audience equally.

The second movement was the respite, which opened with the harp and the ropes torn. The English horn issued a complaining and simple melody, as if trying to evoke older memories of an almost forgotten moment.

Westwood Methodist Church. Although the performance space of the Palisades Symphony Orchestra, the Lutheran Church in Pacific Palisades, was still intact, months of cleaning soot and eliminating smoke smell.

The third movement was recovery. In question and counterpoint, the musicians made a feeling of the possibility that perhaps they can return to the houses that had already lost the community that had accepted them almost 60 years ago.

The public applauded and cheered. Kuzin swallowed the eyebrow, and Hulhage, Bendix, Hanna and the rest of the orchestra stopped and bowed.