When dementia becomes a major factor in any household, the ravages of loss soon begin. It is in that unsettling space, where confusion takes over all parties, that Japanese filmmaker Kei Chika-ura creates his intricately heartbreaking “Great Absence,” about an unresponsive father’s dementia and an estranged son’s investigation into his past.

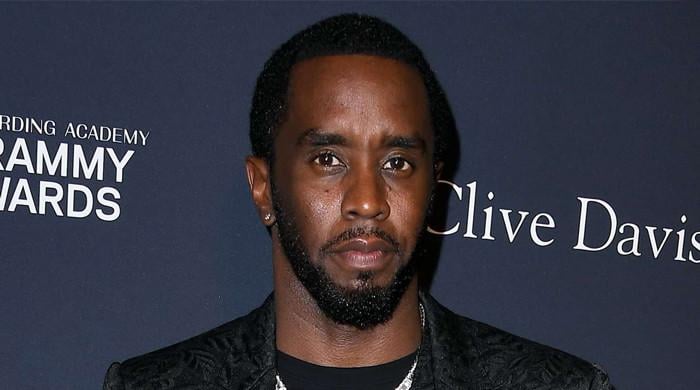

Building on an excellent script (by Chika-ura and Keita Kumano) that is a finely honed model of narrative empathy, and featuring an unprecedented portrait of decadence from the great Tatsuya Fuji (“In the Realm of the Senses”), it conveys profound insight into a difficult situation while intriguingly allowing some workings of the heart and mind to remain impenetrable.

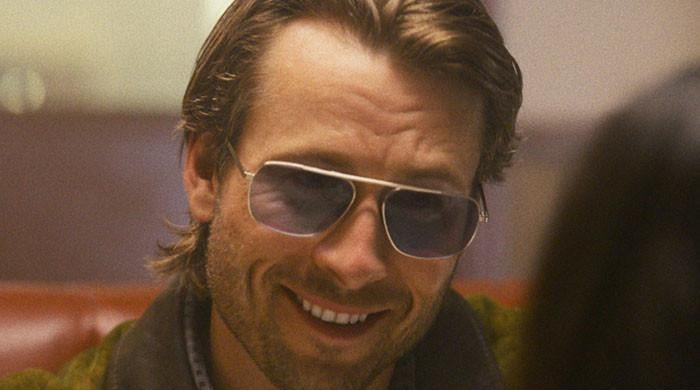

When Tokyo-based actor Takashi (Mirai Moriyama) learns that his retired professor father Yohji (Fuji) has been involved in a disturbing police incident, he travels to his hometown on the island of Kyushu, more out of a grudging sense of responsibility than an act of love, because Takashi, the son of divorced parents, has remained estranged from his father for decades.

With the help of Takashi’s producer wife, Yuki (Yoko Maki), the man facilitates Yohji’s admission into a care facility (which the old man is convinced is a prison in another country) and begins to sort through a house to which Yohji will likely never return. It’s cluttered not only with the remnants of a long life, including the ham radio equipment that became his lifelong obsession, but also with reminders of instructions scrawled everywhere, as if it were the scene of a crime against memory. There is one thing to sort out, though: the fact that Yohji’s second wife, Naomi (Hideko Hara), the woman for whom he left Takashi’s mother all those years ago, has apparently disappeared.

With Yohji, who doesn't understand reality, an obviously unreliable source and Naomi's bitter adult son (Masaki Miura), from her previous marriage, acting cautiously about her whereabouts (Takashi's father treated his mother “like a housewife,” he spits), Takashi must solve the mystery of Yohji and Naomi's life together himself. But he has a valuable source of information in a thick diary stuffed with letters. What emerges is a complicated and revealing love story.

The film’s power lies in its time-shifting structure, which incorporates the recent past into the present story as if they were alternating currents. From flashbacks, beginning with one of Takashi’s tense visits home, we see a long-standing marriage crumble under the worsening mood of an increasingly temperamental Yohji (made absolutely vividly by Fuji) and the steadfast, smiling resistance of Naomi, played with exquisitely understated suffering by Hara. In the present, however, Takashi, absorbing the diary as if he were researching a complicated role, is slowly unraveling as he discovers an emotional life in his father that he never knew anything about and certainly never sensed since those days when all he could do was endure his disapproving judgment.

“Great Absence,” which winks just right at its pandemic time frame to imbue an added nuance of isolating sadness, is as painfully acute as any film in portraying the impact of an aging society on the next generation. That includes the stark difference in partnerships between Yohji and Naomi’s patriarchal marriage, and the more equal arrangement shared by Takashi and Yuki, but also in the ripple effects of a difficult man suddenly needing his own help. In its patient but coiled atmosphere and pleasingly firm plot, Chika-ura has made something novelistic about a man’s dissipating sense of self. But as he disappears, he finds unlikely support in the awareness of his distant son. This makes “Great Absence” a captivating and moving transfer of understanding across time and memory.

'Great absence'

Unrated

In Japanese, with subtitles.

Execution time: 2 hours, 13 minutes

Playing: Premieres Friday, July 26 at the Laemmle Monica Film Center, Laemmle Glendale