Garth Hudson, the stoic multi-instrumentalist and co-founder of the Canadian roots-rock group The Band, died Tuesday in a nursing facility in his adopted hometown of Woodstock, New York. He was 87 years old.

His death was confirmed by the Toronto Star, which attributed the news to the executor of Hudson's estate and said he “passed away peacefully in his sleep.” Hudson was the last surviving original member of the Band following the death of Robbie Robertson at age 80 in 2023.

Over the course of a lifetime of music, Hudson, whose full beard, professorial demeanor and musical gifts added an academic gravitas to the Band through his work on electric organ, accordion and saxophone, played with artists such as Bob Dylan, Emmylou Harris , Neil Diamond, Norah Jones. , Neko Case and Ringo Starr.

Although his bandmates did most of the talking in interviews and on stage, Hudson's musical textures, many of them inspired by old Canadian and American folk songs, were essential elements of the band's sound on classic rock standards such as “The Weight”, “The Night They Drove”. Old Dixie Down” and “The Way I Am.”

Hudson famously worked as a recorder operator and de facto engineer when, in 1967, Dylan moved to Saugerties, New York, to recover from a motorcycle accident and began recording sessions with Hudson's bandmates Robbie Robertson. Rick Danko, Levon Helm and Richard Manuel in the basement of a house they called Big Pink. Hudson's recordings served as the basis for Dylan and the Band's seminal album, “The Basement Tapes,” officially released in 1975, and “Music From Big Pink,” the Band's debut album in 1967.

Hudson's stately bearing belied his roots as a rocker. Anyone who saw his work in “The Last Waltz,” Martin Scorsese's 1978 documentary about the band's final performance, will remember Hudson's skills. Looking more like a 19th-century senator than a late-1960s hitmaker, during the film he approached the microphone to play an alto sax solo on “It Makes No Difference” as if approaching a music stand. to give a speech. When he did, he stuck to the word with effortless elocution.

“Different musical styles are like different languages,” Hudson told Canada's Globe and Mail in a rare interview in 2002. “I can play a lot of instruments so I can learn the languages.” He added: “It's all country music; It just depends on what country we are talking about.”

The Band, from left, Garth Hudson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, Levon Helm and Robbie Robertson.

(GAB/Redferns Archive)

Born on August 2, 1937 in Windsor, Ontario, Eric Garth Hudson was the son of a musically inclined father, Fred Hudson, who was a fighter pilot in the First World War before becoming an agricultural inspector and accordion and piano musician. Performing mother Olive Hudson began teaching her son both instruments as a child.

In addition to formal training, like many teenagers of the era, Hudson's musical tastes were informed by Alan Freed's rock 'n' roll radio show “Moondog Matinee,” which broadcast from Cleveland. “That's when I realized there were people there having more fun than me,” Hudson said, quoted in Greil Marcus's tome “Mystery Train.” Hudson joined his first band when he was 12 and spent his teenage years playing piano and saxophone. with rock and jazz outfits.

In 1957, he co-founded Silhouettes, which became Paul London and the Capers. The band occasionally ventured south to Chicago and Detroit, and even traveled west on tour to play the famed Lighthouse jazz club in Hermosa Beach. “We had been playing for a couple of months before the Border Patrol told us to go home,” Hudson, who spoke with a measured Southern accent when he bothered to speak in public, told the Globe and Mail. “We were told we had to get permanent work visas, which at the time were mainly given to hockey players and wrestlers.”

In the late 1950s in Toronto, Hudson met the other four members of the band when they were hired to tour with rock 'n' roll singer Ronnie Hawkins. Within a few years, the Hawks became a tight, studied backing band. As they gained momentum, they left Hawkins in 1963 to tour on their own, touring southern Canada and across the border to East Coast clubs. Dylan connected with the future band during one of these stops and invited them to tour Europe with him. During these tours, Dylan officially “went electric” for half of each concert.

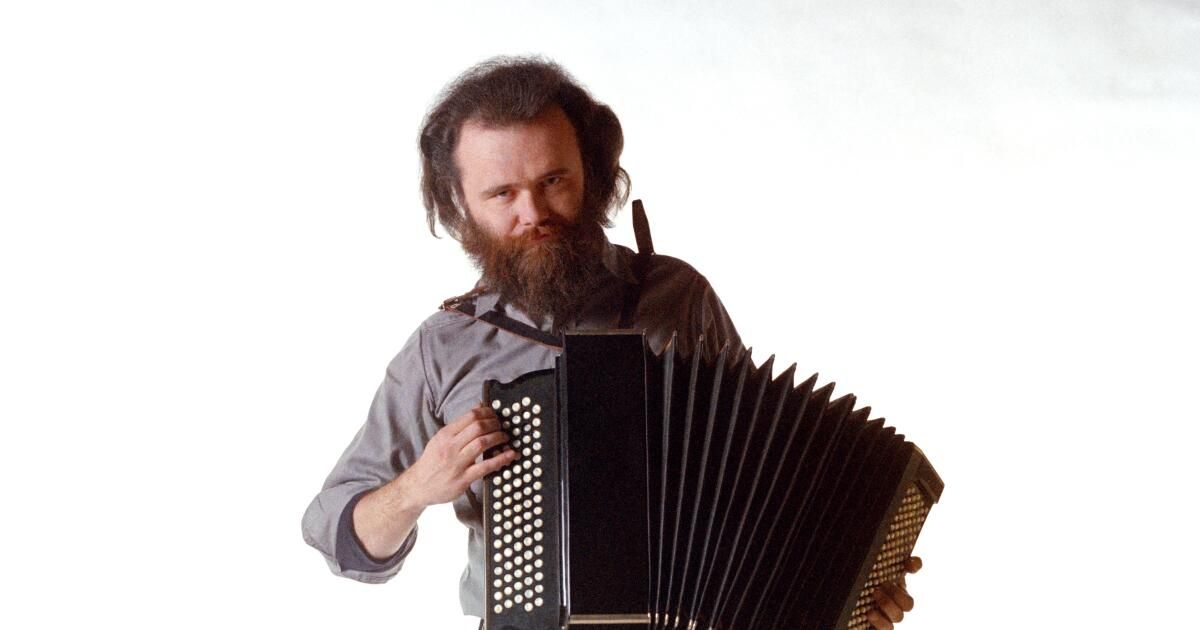

Garth Hudson performs during “The Last Waltz” on November 25, 1976 in San Francisco.

(Ed Perlstein/Redferns)

That's Hudson powering up his trademark Lowrey organ during Dylan's fiery performance of “Like a Rolling Stone” at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, England, on May 17, 1966. He played those overwhelming first notes after an angry, loving fan of folk shouting “Judas!” at Dylan for betraying his folk roots. That outburst was largely due to the noises of Hudson's organ.

Hudson and the rest of the band arrived at Dylan's home in Saugerties the following year. Every morning, the Band would wake up in Big Pink and prepare for rehearsals. Hudson came down early to make sure the recorder was ready for Dylan's arrival. As the day's sessions began, Hudson sat in a corner near his organ and pressed “record.”

“The wonderful thing about working with Dylan was the imagery of his lyrics, and I was allowed to play with those words,” Hudson told Keyboard magazine in 1983. “I didn't do it incessantly. I didn't try to capture the clouds or the moon or whatever every time. But I would try to introduce something small at one point about a third of the way through the song, which might have something to do with the words that were happening.”

Hudson added that when he was starting out, he tried the more popular Hammond B-3 organ, but was drawn to a model made by a smaller company, Lowrey. “The Lowrey had enough punch and I could distort it enough to fit what we were doing.” Early models, Hudson continued, exploded with “a big distorted sound when you turned it up all the way up.”

Hudson recorded 1968's “Music From Big Pink” just as he had done the Dylan sessions. Writer Marcus described the album in “Mystery Train” with a sense of reverence: “Flowing through its music were spirits of acceptance and desire, rebellion and wonder, raw emotion, good sex, open humor, a magical feeling for history.” , a determination to find plurality and drama in an America that we had too often found to be a monolith.”

That album and its 1969 follow-up, “The Band,” cemented his reputation among critics, but failed to register with a youth market then obsessed with LSD and psychedelic music. When the sound the band helped forge, country-rock, became a commercial powerhouse a few years later, they saw bands like the Eagles, Lynyrd Skynyrd and compatriot Neil Young rise to the top of the charts. The Band released five studio albums between 1970 and 1976. None were major commercial successes, but the musicians remained a powerful live band. Dylan invited them to embark on a joint tour in 1974, which that same year was the basis of Dylan's first live album, “Before the Flood.”

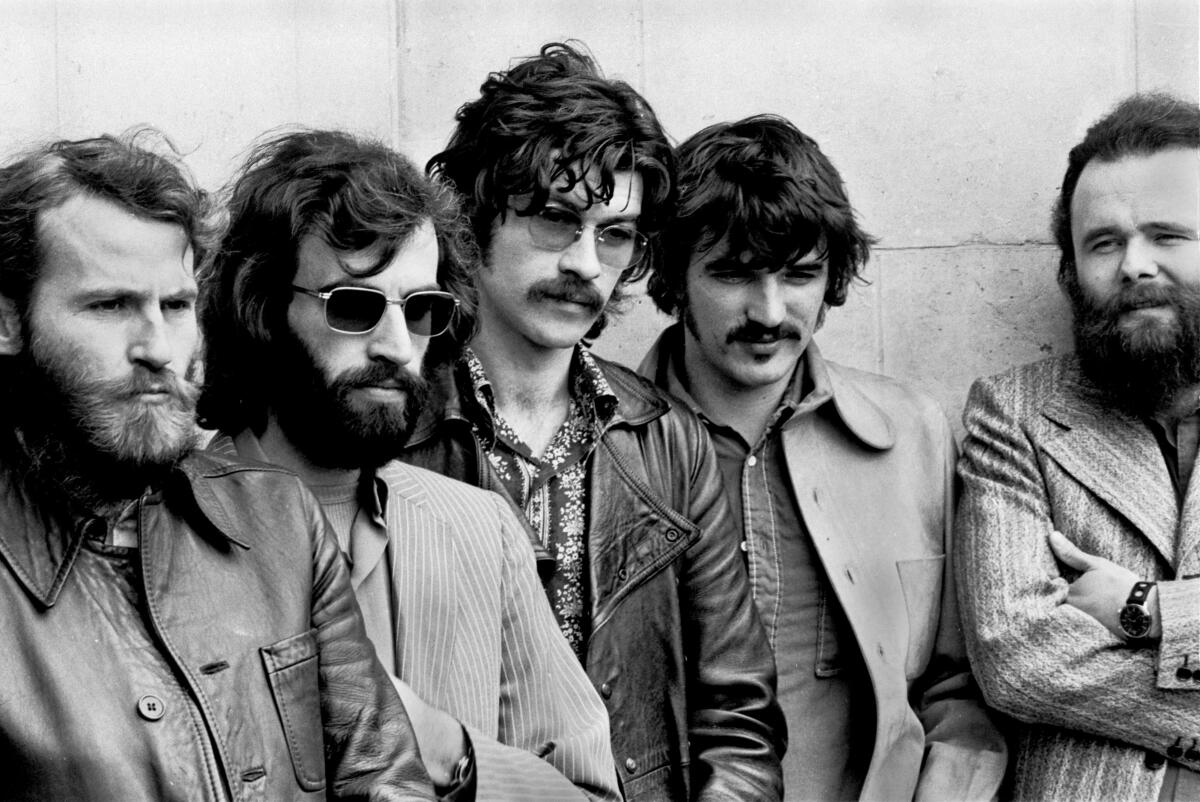

The Band, left, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel, Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko and Garth Hudson in London, June 1971.

(Gijsbert Hanekroot / Redferns)

In the mid-1970s, Hudson and most of his bandmates (drummer Helm split his time between Los Angeles and Arkansas) moved to Malibu to help create another legendary studio, Shangri-La. With Dylan investing alongside the band, they rented a house, supposedly a former brothel, and converted it into a state-of-the-art recording studio. Hudson purchased a nearby property that he named Big Oak Basin Dude Ranch. By then, however, the band had been together for almost 15 years. They broke up in 1976 amid various addictions and life changes, but not before releasing “Islands,” the last studio album featuring the original lineup. He and his wife, Maud Hudson, lost their home and belongings in the Agoura-Malibu fire in 1978. (Shangri-La is now owned by producer Rick Rubin.)

With the band's demise, Hudson adopted a steady life as a session musician, appearing on records by Poco, Van Morrison, The Call, Camper Van Beethoven, Mary Gauthier and many others. Without Robertson, the band partially reformed in 1983 to tour and spent the next three years headlining and on bills with the Grateful Dead and Crosby, Stills and Nash. After Manuel's suicide in 1986, the band returned to the studio for 1993's “Jericho,” but Robertson again did not join Hudson, Helm and Danko.

Hudson's work on fellow Canadian Neko Case's acclaimed 2000s albums, “Fox Confessor Brings the Flood” and “Middle Cyclone,” reinforced the ways in which his often menacing organ chords and magnificent Improvised countermelodies have resonated through generations.

Garth Hudson in 2014.

(Rick Madonik/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Approaching old age, Hudson and his wife returned to the Hudson River Valley. His life as a non-songwriting member of the band meant that he did not own a percentage of any of the band's songs and therefore did not receive regular publishing royalties from their work. By then, Hudson had long since sold his share of the Band to Robertson.

In 2013, Hudson made headlines when the owner of a New York storage space threatened to auction off his memorabilia for non-payment. Already saddled with at least three bankruptcies, he struggled to regain control of his files.

Maud Hudson died at the end of February 2022. The couple had no children.

Along with his bandmates, Hudson was inducted into Canada's Juno Hall of Fame in 1989 and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1994. In 2008, he and the band received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

Garth Hudson released two solo albums: “Music for Our Lady Queen of the Angels” in 1980 and “The Sea to the North” in 2001. Mix of styles, synth and organ tones, a Vocoder voice box and a program. Despite the rock album's tempo changes, on both releases, Hudson composes and plays as if his muse can barely contain all the ideas that flow.