Book review

If you buy books linked to on our site, The Times may earn a commission from bookstore.orgwhose fees support independent bookstores.

“That's my pot dealer!” exclaimed Michelle Phillips in a packed theater in 1977. Months earlier, the Mamas & the Papas singer had only known Harrison Ford as a stoner-carpenter with a few small roles under his belt. Now he was Han Solo in “Star Wars,” directed by a young upstart, George Lucas. Clearly the world was changing.

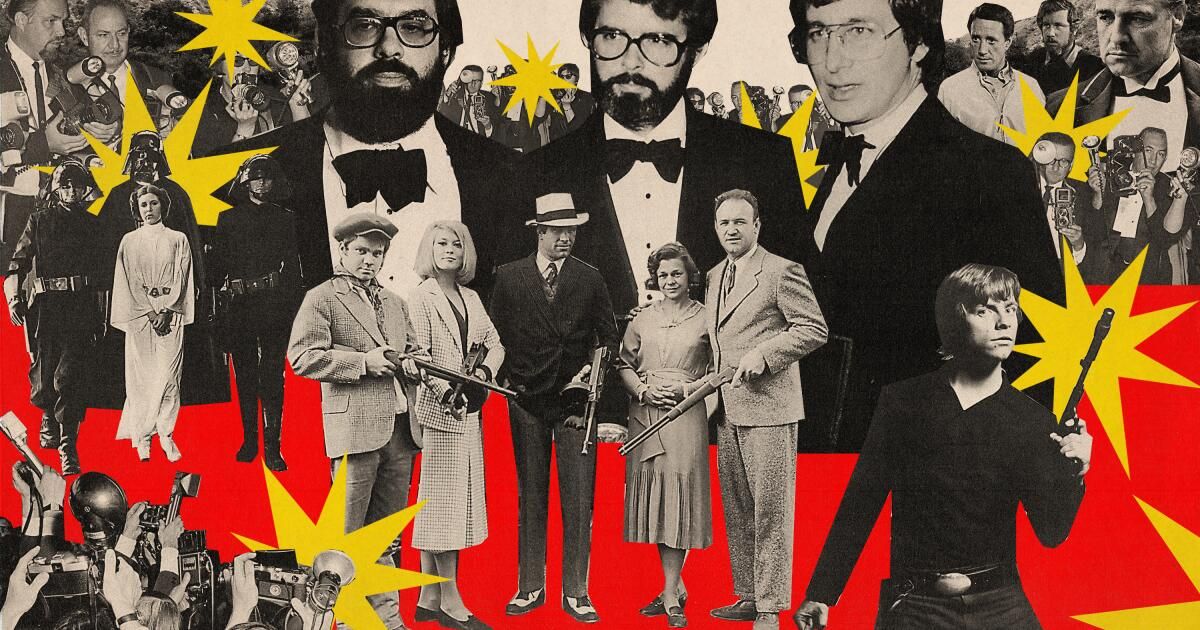

How much? Conventional wisdom about the Hollywood renaissance of the 1960s and 1970s suggests that starting with “Bonnie and Clyde” and “Easy Rider,” a group of emerging auteurs lifted studios out of their ruts and transformed American cinema. There's a lot of truth in that: Francis Ford Coppola's shift in 10 years from hired director on an early musical, “Finian's Rainbow,” to auteur behind “Apocalypse Now” is just one of the era's most notable achievements.

A couple of new books, however, suggest that the overall change was only to a certain extent modest, ultimately underpinning not only the old-school system of studies but also the social norms that the interlopers were supposed to be disrupting.

Paul Fischer's lively story of the new wave of California directors, “The Last Kings of Hollywood,” focuses on Lucas, Coppola and Steven Spielberg. (New York contemporaries like Martin Scorsese and Brian De Palma are present but relatively offscreen.) Fischer has a gift for highlighting the ways in which moments we now accept as inevitable were often the product of bad luck, pyrrhic victories, and difficult decisions. Coppola made “The Godfather” out of financial desperation, reluctant to adapt a mafia novel; Spielberg's “Jaws” was plagued with setbacks, from a reckless attempt to train a real shark to its mechanical malfunction; Only when Lucas learned that the rights to Flash Gordon were not available did he look for a space opera concept of his own.

Their chutzpah and entrepreneurial spirit were to be applauded: While the trio produced films that broke box office records (“The Godfather,” “American Graffiti,” “Jaws” and more), there was reason to believe that big-budget films could operate outside the studio system. Lucas in particular was driven by both resentment of the old and passion for the new. He never forgot how Warner Bros. mishandled his debut feature, “THX 1138,” and he was forced to create “Graffiti” to spite the defendants who said he couldn't. In 1969, Coppola and Lucas launched their own studio, American Zoetrope, in San Francisco, with a number of scripts in the works (including “Apocalypse Now” and “The Conversation”) and a $300,000 investment from Warner Bros. But Coppola wasn't much of a businessman, and he found it easier to run the office's fancy espresso machine than the suite of state-of-the-art editing stations: “He runs his business like he ran a film set, with vibes,” Fischer writes.

A decade later, both Coppola and Zoetrope would declare bankruptcy and he would split from Lucas, who had used the success of “Star Wars” to make his way as a kingmaker in Hollywood through his own production company, Lucasfilm. It allowed him to indulge his love for classic thriller series and chose Spielberg to direct “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” But Fischer frames Lucas' career as a disappointment, despite all those dollar figures: Lucas wanted to return to more artistic “THX”-style fare, but needed cash flow. “If George was ever going to be independent of Hollywood, he thought he wouldn't make it by making abstract mood poems,” Fischer writes. By the '80s, with two “Star Wars” sequels completed, Lucas was completely out of the mood poem business.

While “Last Kings” focuses exclusively on the directors' relationship with the film economy, Kirk Ellis' “They Kill People” considers “Bonnie and Clyde” and New Hollywood from a variety of angles: film, the social upheaval of the '60s, America's complex relationship with outlaws in general and guns in particular. It is a meaty but accessible book that captures the lightning-in-a-bottle nature of the original generation text, capturing the improbable nature of its creation and the somewhat dubious nature of its legacy.

“Bonnie” was such a provocation (naked, almost dizzyingly violent) that its studio, Warner Bros., almost wished it didn't exist. It was given a shoestring budget, mocked by studio boss Jack Warner (who sarcastically referred to director Arthur Penn and producer-star Warren Beatty as “the geniuses”), and initially released primarily to Southern drive-ins. “They thought farm kids would like guns,” Penn said.

Everyone liked the weapons. Some critical critics lamented the film's violence, especially its then-shockingly bloody ending, but Beatty and co-star Faye Dunaway were deeply seductive on screen. (Ellis notes that the two are always the best-dressed characters in the movie.) And its outlaw sensibility resonated with young audiences in the late '60s. Furthermore, writes Ellis (a historical drama screenwriter best known for “John Adams”), it represented the culmination of decades of American culture that equated gun culture with freedom, a notion that would have baffled the founding fathers, who dwelt little on gun rights issues in the Federalist Papers and other constitutional-drafting documents but gained traction from gun manufacturers. “In the printed legend of American history, guns and freedom have become synonymous,” Ellis writes, but this was a new legend, fueled in part by “Bonnie and Clyde,” not the story of America's origin.

It would be a mistake to reduce New Hollywood to the filmmakers highlighted by these two books; although, focused as they are on white men, they echo the way women and people of color were largely excluded from the system or relegated to more marginal blaxploitation jobs. Artists looking to trade outside the system have plenty of inspiration to draw from in the '70s. However, the books also expose how trading does what it always does: accept provocations, sand them down, and then look for ways to make them profitable. In the early '80s, a decade after Coppola and company stormed the barricades, Paramount boss Michael Eisner shared a new and contradictory vision, such as it was: “We have no obligation to make history. We have no obligation to make art. We have no obligation to make a statement. Making money is our only goal.”

It would take another decade – and East Coast authors – to launch another attack on that sensibility, through films like “Do the Right Thing” and “Sex, Lies and Videotape.” They would help usher in the Miramax era, but that's another story, with its own problematic twists.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The new Midwest.”