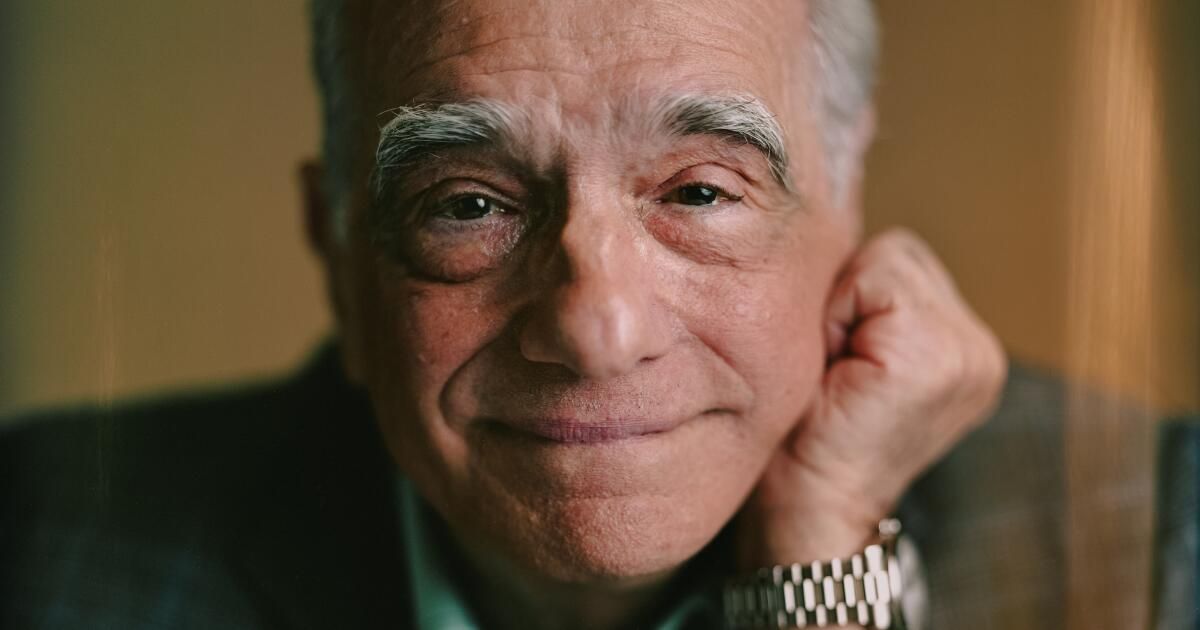

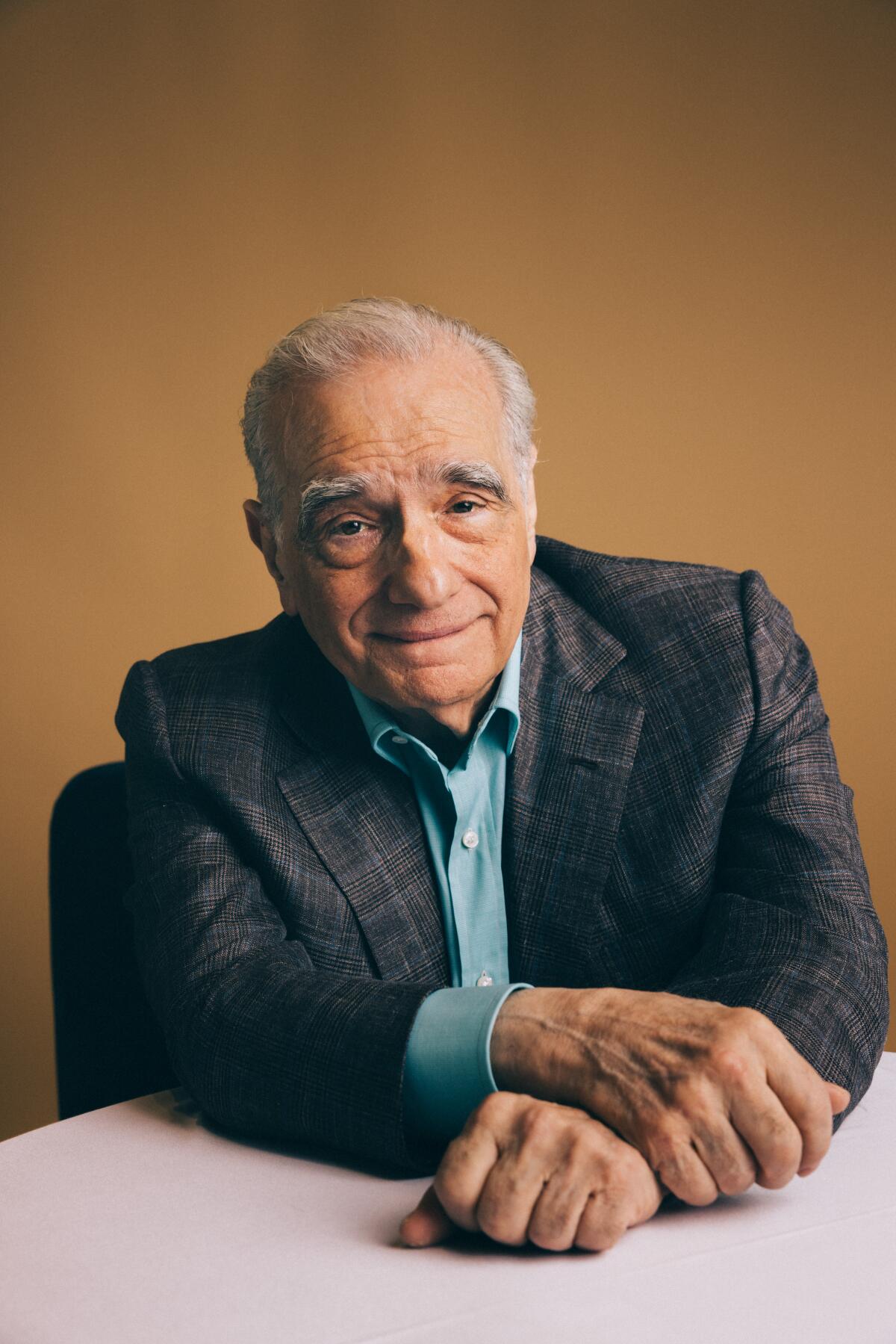

“We are decent and then we learn to be indecent? We can change? Will others accept that change? These are some of the themes that Martin Scorsese explores in his work.

(Jay L. Clendenin/Los Angeles Times)

Forget the ghosts of Christmas past. Martin Scorsese has been thinking lately about dear friends who died at another Christmas celebration, Thanksgiving in Los Angeles at the small house on Mulholland Drive that he shared with musician Robbie Robertson. It was an “extraordinarily happy” occasion, Scorsese recalls, 45 years after the fact, when he had just been released from the hospital, a surprising turn of events, since he firmly believed he was going to die.

So to celebrate, he hired someone to cook a Thanksgiving dinner (he barely knew how to boil water) and invited a group of friends, including an Italian producer working on Michelangelo Antonioni’s next film. Is it okay if I take Mr. Antonioni to his house? the producer asked. Of course. The more the better. But as the evening progressed, Scorsese remembers that Antonioni, a filmmaker adept at conveying distance and emotional alienation, couldn’t understand why Scorsese and Robertson continued to laugh so much.

“We couldn’t really stop,” Scorsese says. “He was alive, to begin with. And I started working on ‘Raging Bull’. I was back on track after a long period of trying to find a way to continue, a reason to be excited about the prospect of going to a movie set. For a long time I doubted whether I still had enough to worry about to make a film. Now I did it.”

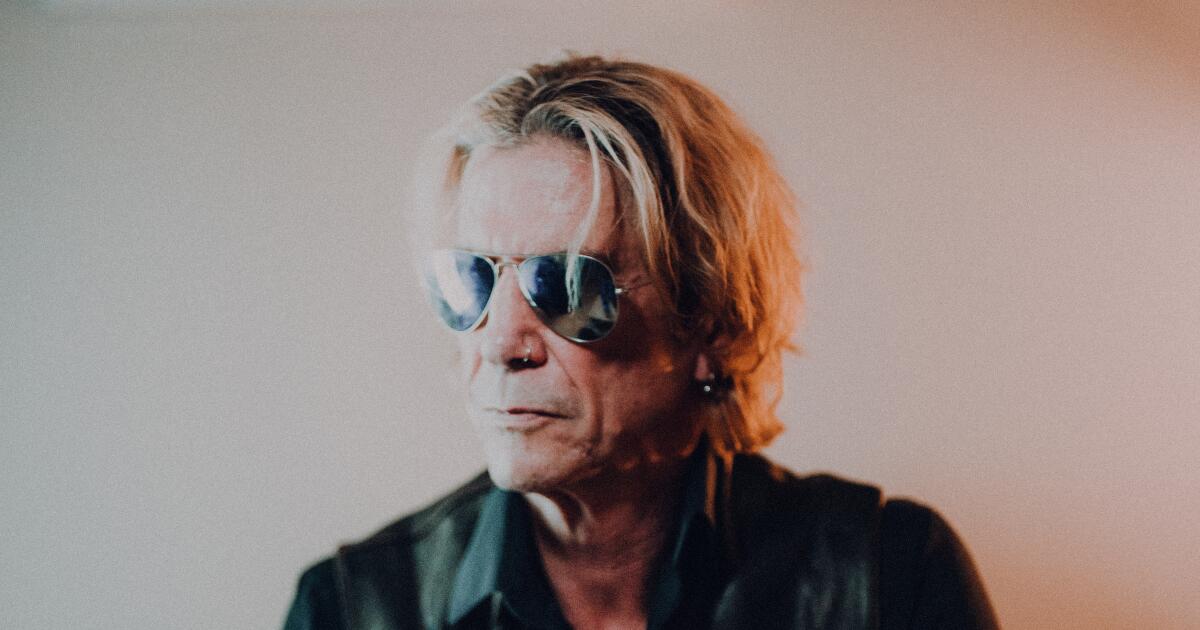

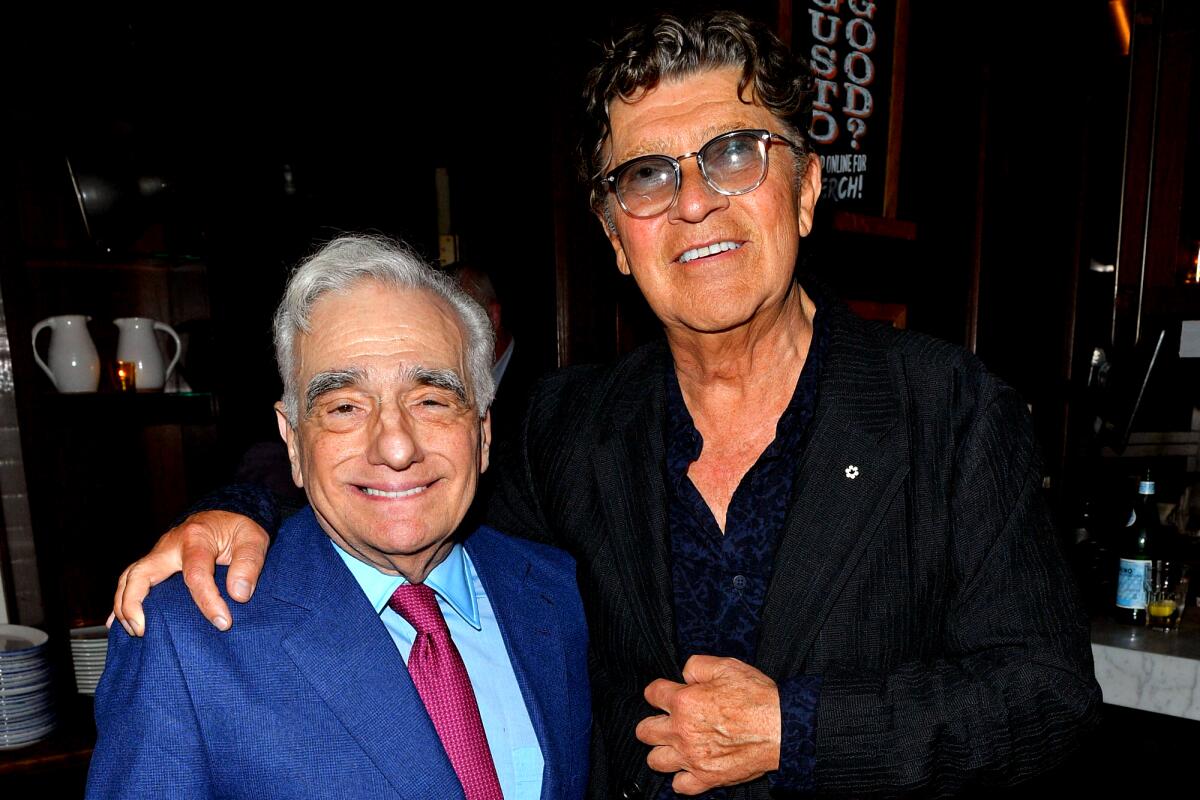

It’s a rainy winter day in Los Angeles and Scorsese is gathering his thoughts for a speech he’ll give later tonight at a celebration of Robertson’s life and music. Robertson died in August, shortly after his final musical collaboration with Scorsese, the Cannes Film Festival audience hearing the score to the filmmaker’s latest masterpiece, “Killers of the Flower Moon.” After our conversation, Scorsese delivered a moving 17-minute remembrance of his friendship with Robertson, which began with the concert film “The Last Waltz” and continued through collaborations on films such as “The King of Comedy,” “Silence.” and “The Wolf of Wall Street.”

Martin Scorsese and Robbie Robertson at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2019.

(George Pimentel/Getty Images)

Under the circumstances, our thoughts couldn’t help but drift to Robertson and the years Scorsese spent in Los Angeles in the ’70s. Scorsese arrived in early 1971 at the behest of Warner Bros. executive Fred Weintraub and rented an apartment in Franklin Avenue in Hollywood because it reminded him of his native New York.

“Freddie said go out for two weeks, try it and it won’t ruin you too much,” Scorsese says. “I spent the first year getting acclimated and learning to drive. “It was a new world.” He smiles. “I started wearing jeans.”

Actor David Carradine told Scorsese he needed a flashier car than the rental car he was driving and found a 1960 Corvette, white with red leather interior, to buy for $500. It was difficult to drive – “you had to be a real expert to do it,” says Scorsese – particularly because he didn’t know how to operate the clutch. But Scorsese learned and began to enjoy driving the Corvette around town, if only to turn on the radio and listen to new music from Bob Dylan, Van Morrison, Eric Clapton and the Grateful Dead.

“The music always created images that precipitated dramatic scenes and eventually became ‘Mean Streets,’ ‘Taxi Driver,’ ‘Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore,’” Scorsese says. “Driving down the highway at 2 in the morning without cars and listening to the Allman Brothers could inspire a lot of thoughts. My first connection with creativity was always music, going back to the 78 records my father played for me when I was 5 or 6 years old: Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey and Django Reinhardt at the Hot Club in France. Images came to mind as I listened. They were abstract, but they made me move my head.”

“People always use this phrase as a joke – ‘peace, love’ – but it’s not funny. Those are things to aspire to,” says director Martin Scorsese.

(Jay L. Clendenin/Los Angeles Times)

The early years in Los Angeles essentially gave Scorsese the opportunity to deny where he was from and try on a new identity. he started using cowboy hats and boots, big belt buckles, Nudie shirts, lots of denim. People laughed at him. That? Are you a cowboy now? But he was doing “Alice Doesn’t Live Here” in Tucson, and the clothes suited the climate and the culture. Additionally, Scorsese grew up watching John Ford westerns. He now he could pretend he lived in one.

But when Scorsese moved into the Mulholland house (his doctor told him he needed to get over the smog line to help control his asthma), he was depressed and suffered his first flop, the 1977 musical “New York, New York.” and fighting creative paralysis. All the cocaine didn’t help either. When he finally entered the hospital with internal bleeding, just before the 1978 Thanksgiving holiday, Scorsese had come full circle, confronting who he was and where he came from.

“It’s over,” Scorsese says of his time in the West. Finally he had finished “The Last Waltz,” the elegiac documentary of the band’s farewell concert, which, in itself, seemed a harbinger of change. “It was the end of that music and unfortunately people always use this phrase as a joke – ‘peace, love’ – but it’s not funny. “Those are things to aspire to.”

Scorsese has been on a creative streak over the past decade, making an irreverent black comedy about unbridled greed (“The Wolf of Wall Street”), a passion project about faith and doubt (“Silence”), a tinged crime epic of betrayal and regret (“The Irishman”) and now “Killers of the Flower Moon,” an epic exploration of exploitation, injustice and erasure. “Freedom,” he says when asked about the key to this latest streak. He has gone from a “barbarian knocking on the doors of Rome” to an elder statesman buoyed by generous independent funding.

“But still scrapping or scraping or however you want to put it,” Scorsese says, laughing. “‘Silence,’ ‘The Irishman,’ ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’…they weren’t movies that studios were eager to make.”

“Do you see those three movies talking to each other?” Asked.

“I tried to find in ‘Kundun’ and ‘The Last Temptation of Christ,’ even ‘Gangs of New York,’ to some extent, paths to redemption and the human condition and how we deal with the negative things inside of us.” , Scorsese says. “We are decent and then we learn to be indecent? We can change? Will others accept that change? And I think it’s really a fear of a corrupt society and culture because of its lack of foundation in morality and spirituality. Not religion. Spirituality. “Deny that.”

“So for me, it’s finding my own way in a… if you want to use the term ‘religious’ in the sense, but I hate using that language, because it’s often misunderstood,” he continues. “But there are core beliefs that I have, or I’m trying to have, and I’m using these movies to find them.”

Lily Gladstone and Martin Scorsese on the set of “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

(Melinda Sue Gordon / Apple TV+)

“Killers of the Flower Moon” tells the true story of morally reprehensible men bent on murdering dozens of members of the Osage Nation to gain their rights to oil-rich land in Oklahoma in the 1920s. Ernest Burkhart, played by Leonardo DiCaprio , he marries an Osage woman, Mollie (Lily Gladstone), and then, under instructions from his uncle, William Hale (Robert De Niro), sets out on a plan to help kill his relatives. However, Ernest seems to genuinely love Mollie. Can a man devote himself to his wife and exterminate his family?

“Yes, exterminate his family and, for all he knows, help exterminate her,” Scorsese responds. “His weakness reminds me of Kichijirō’s character in ‘Silence’ that he keeps apostatizing and then he keeps asking for forgiveness and then, to make matters worse, he betrays the priests and then confesses and asks the priest for forgiveness. So what is the Christian way? Should the priest forgive him? And if he forgives him, how does he control his own hatred and anger towards this guy?

Scorsese shakes his head, pondering the question for a moment.

“That type of forgiveness is almost an impossible goal for human beings,” he continues, lowering his voice until it becomes a whisper. “But I really believe in it. If we encourage forgiveness, perhaps the world can ultimately change. I’m not saying next year. “It could be a thousand years from now, if we’re still around.”

After “Killers of the Flower Moon” premiered in Cannes in May, Scorsese traveled to Italy with his wife, Helen Morris, to attend a conference titled Global Aesthetics of the Catholic Imagination. Afterwards, he briefly met with Pope Francis and then announced: “I have responded to the Pope’s call to artists in the only way I know how: by imagining and writing a script for a film about Jesus.”

Scorsese completed the script for that film, collaborating with critic and filmmaker Kent Jones, and plans to film it later this year. They are still “swimming in inspiration,” he tells me, still figuring it out. It will be based on Shūsaku Endō’s book “A Life of Jesus.” (Endō also wrote “Silence”). And it will take place primarily in the present day, although Scorsese doesn’t want to be locked into a certain period, because he wants the film to feel timeless. He imagines the film will be around 80 minutes long and will focus on the core teachings of Jesus in a way that explores the principles but does not proselytize.

“I’m trying to find a new way to make it more accessible and remove the negative charge of what has been associated with organized religion,” Scorsese says.

Every time the word “religion” has come up since we started talking, I say you’ve tried to find a way to avoid it.

“Right now, you say that word ‘religion’ and everyone is up in arms because it’s failed in so many ways,” Scorsese says. “But that doesn’t necessarily mean that the initial impulse was wrong. Let’s go back. Let’s think about it. You can reject it. But it could make a difference in how you live your life, even by rejecting it. Don’t dismiss it suddenly. That’s all I’m talking about. And I say that as a person who will be 81 years old in a couple of days. You know what I’m talking?”

He is asking. But he doesn’t ask. Who wants to go there and think about that? Later, however, we start talking about the scene in “Killers of the Flower Moon” where Mollie’s mother, Lizzie, dies and peacefully enters the afterlife, greeted and guided by her ancestors. The weather was perfect that day, Scorsese says, and when Lizzie left with her mother, her father and her ancestors, he kept the camera rolling for a long time.

“The whole team could feel it. “It was the Champs Elysées,” says Scorsese. “And we thought, ‘That would be the best way to do it.’ They just take us home.’”