On a show that features guest appearances by the likes of Emma Stone, Bowen Yang, Amy Sedaris and Aidy Bryant, Julio Torres’ “Ghosts” could very well make a TV star out of someone who aptly has only one name: Martine.

“This is the most important role I’ve ever played in my life,” Martine, a trans visual and performance artist, says via Zoom. “I’m officially the star of a TV show. And it might be my favorite TV show, too.”

For anyone who has seen “Ghosts,” that recommendation should also serve to give insight into Martine’s aesthetic and artistic sensibility, because “Ghosts” is not like any other television show.

The six-part urban fairy tale, which premiered June 7 on HBO and releases episodes weekly on Fridays through July 12, imagines a New York City where ExxonMobil builds developments and ride-sharing apps called Chester, with a driver named Chester, exist alongside mermaid sales reps and rodent nightclubs turned CVS pharmacies.

Within this fantastical vision of New York, Julio (Torres) (who was struck by lightning as a child and is allergic to the color yellow) is constantly trying to make ends meet with the help of his robot assistant, Bibo (voiced by Joe Rumrill), and his agent, Vanesja (the “j” is not pronounced), played by Martine.

“The show itself is a kind of post-genre,” Martine suggests. “It’s very much a genre-building show. It’s hard to explain what you can expect to see.”

Every scene in “Ghosts” — whether it’s a comedy called “MELF” that references “ALF” and features Paul Dano, or a vignette centered on an eager customer service representative played by “Euphoria’s” Alexa Demie — bares its elaborate theatricality. It’s always clear that the audience is watching something filmed on a set, with painted backdrops and improvised props. This is a fantastical world that never pretends to be anything more than an absurdist, absurdist take on everyday life.

1

2

1. Paul Dano, right, appears in a parody about an “ALF”-like puppet named MELF. (Atsushi Nishijima/HBO) 2. Alexa Demie plays an overzealous customer service representative. (Monica Lek/HBO)

“It felt like a play,” Martine says of working on the show. “It was like being on a stage with an audience. Everything was built within a giant set and everything was repurposed: the school became a nightclub, the nightclub became a rooftop. And the audience was everyone on the set.”

In this fun-filled mirror of a show, which combines sketch comedy with a ridiculous plot that finds Julio wanting to avoid getting an ID that would serve as his “proof of existence,” Martine was also encouraged to play with her own identity, as a performer, artist, and actress.

“I don’t recognize myself in the show,” she says. “Because it’s Vanesja. And I think Vanesja came about because I was so nervous about my performance. The only way forward for me was to say, ‘You don’t have to be yourself. You can present some kind of armor, some kind of stronger, idealized persona that you want to move through the world with. ’”

For Martine, the very idea of being “oneself” is elusive. Questioning the rigidity of our sense of self has long been at the heart of her art, which has appeared in galleries and art museums across the country (not to mention the Venice Biennale) and in magazines such as Interview and Artforum.

“Who am I?” he asks himself out loud. “I think I’m constantly trying to get rid of that definition. I think I’m constantly throwing it away, discarding it, shedding it, so to speak, to move on to a bigger, stronger, faster model. Or a predator or something.”

You could say that this playful language, which moves from the inquisitive to the absurd with ease and humor, is the reason she gets along with Torres. Martine met the Salvadoran comedian almost a decade ago at an archery championship. “It’s a really amazing story,” she recalls. “Julio was there at the buffet. He’s vegan, and I was pretending to be vegan at the same time.”

They both reached for the last tater tot, and the moment their fingers touched and their eyes met, Martine knew she had found a new friend. Maybe even more. “This is your sister wife,” she remembers thinking. “This is your soulmate and they are both hungry… to be seen.”

What Torres remembers most about his first meeting with Martine is something equally ineffable: “Her ability to subvert her own physicality, to find humor in beauty,” he recalls via email.

Their friendship blossomed over archery practice and friendly DMs as their careers blossomed in separate yet complementary directions. While Torres joined the writing staff of “Saturday Night Live” and later debuted her own comedy special (“My Favorite Shapes”), Martine was busy creating art installations that satirized advertising campaigns (Martine Jeans), a publication similarly critiquing high-fashion magazines (Indigenous Woman) and sci-fi-set live performances (“Circle”) that played with ideas about gender, femininity and self-expression in equally brazen and wryly earnest ways.

Their previous collaborations (Martine previously played an unimpressed gallery owner in Torres’s feature debut, “Problemista,” and a ham-fisted beauty queen in his Peabody Award-winning show “Los Espookys”) feel like playful preludes to their work together on “Fantasmas.” After all, Vanesja is a performance artist who has played Julio’s talent agent for so long that she’s lost track of whether it’s even a performance anymore.

“Without Martine, there is no Vanesja,” says Torres. “That’s how I work sometimes, collaborating with an artist to create something bespoke for them. She first planted the seeds for Vanesja when she left me cryptic voicemails. Something about closing a big deal and not being able to talk about it. We welcomed each other into our worlds.”

In the surreal world of “Ghosts,” Vanesja is a reminder of how ourselves can often be indistinguishable from the improvised roles we play.

“I think a lot of the motifs from the show exist in my work as well,” Martine says. “I love mannequins. I love asking a lot of general questions about identity and using costumes and characters to try to get at a deeper truth. And it was really refreshing to delve into that with comedy because the art world is so unbearably serious.”

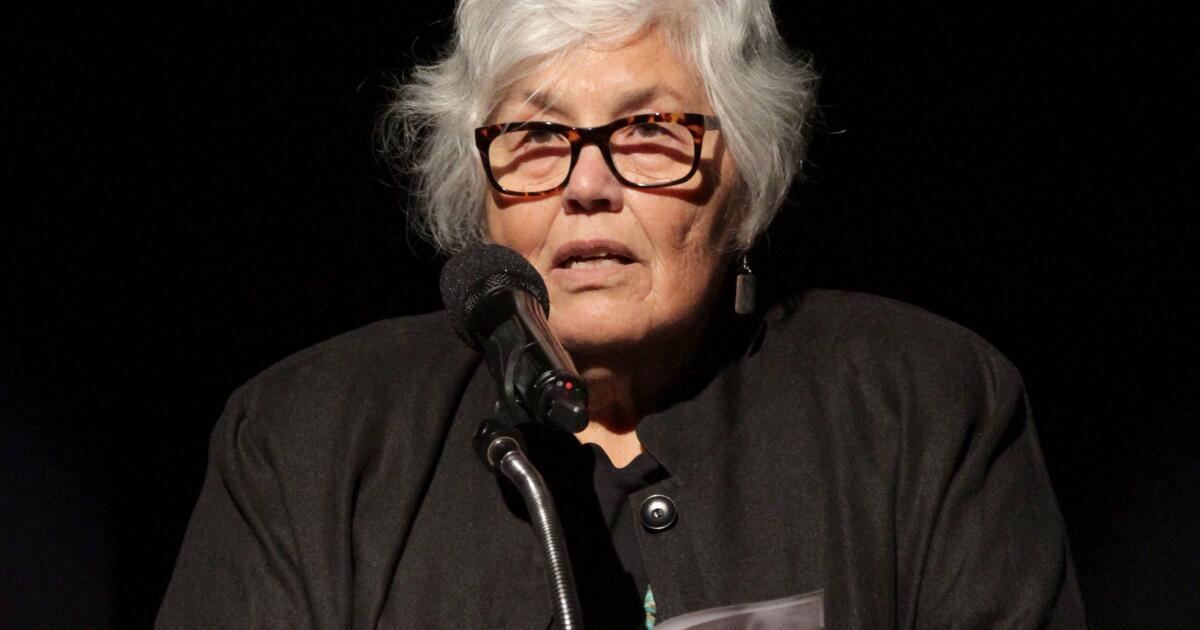

“I love mannequins. I love asking a lot of general questions about identity and using costumes and characters to try to get to a deeper truth,” says Martine.

(Monica Lek / HBO)

In Vanesja, we see Martine reveling in that comedy. With her sense of humor intact and Vanesja’s aesthetic, which yearns to be described as “the reality of a business executive,” she has constructed a wry portrayal of an artist-agent whose indifference to the world around her is fascinating. For starters, there’s her voice, which is sultry and breathy, marked by a glacial rhythm that makes both Julio and the audience become absorbed in her every word. She almost seems straight out of the late 90s, when the blazers and pencil skirts Vanesja wears were synonymous with a brand of feminine, if not overtly feminist, seriousness.

“Vanesja is a classic binary woman,” says Martine. “She has both the charm of a woman and all the strength of a man.”

Working with such a marked gender binary, I wonder bluntly how she was able to create this fascinating character who seems distant but interested, cold but warm. How did she do it?

“How does Vanesja do it?” she asks, laughing, wanting to clarify my question, knowing, perhaps, that she has arrived at a key philosophical way of understanding her process and her character alike. “I play Vanesja every day. I try to play Vanesja at least once a day, just for flexibility and for my health, my mental health.”

For Martine, having the opportunity to create Vanesja alongside Torres was a joy because it allowed her to discover parts of herself and her work that exist on the surface, but at the same time get at deep insights into who we are and how we present ourselves. However, on a purely visual level, she had a very simple reference in mind.

“I’m obsessed with Ursula from ‘The Little Mermaid’ when she becomes a cis woman,” she says. “Her name is Vanessa, and I feel like there’s a resemblance between that Vanessa and me, like when I’m not in drag. This was me trying to implement an evil persona that I personally feel lives inside of me.”

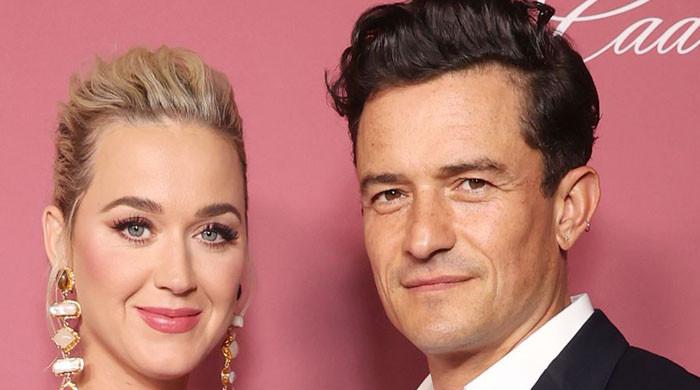

That Disney touch wasn't the only personal touch Martine brought to “Ghosts.” She's responsible for what has already become one of the show's most talked-about images, seen in Friday's episode: her scene partner, “Teen Wolf” star Dylan O'Brien, sporting red lace lingerie, with matching garters and stockings.

Dylan O'Brien and Martine in “Ghosts”.

(Monica Lek / HBO)

“That was probably my only narrative contribution to the show,” he admits. “It’s a matter of personal taste. I think it’s really sexy to see a man in women’s underwear. Dylan had no problem with that. He was very down and looking great.”

Such an incongruous image (in a rather melancholy scene, not really that steamy) doesn’t seem out of place in “Ghosts.” The series, like Vanesja, embraces binaries only to build bridges between them. Or break them. Or maybe just play with them. But it can do so only because the series is fascinated by the personal dramas we all carry within us. There’s a drive toward empathy for the other that runs through the series, even in its most outlandish moments.

“'Fantasmas' is about the people who live there,” says Torres. It is a show “about characters who, with little screen time, seek to capture the curiosity of viewers.”

Echoing those words and trying to sum up the ambitions of this unconventional show, Martine recalls Jon Brion’s song “Little Person,” which he co-wrote with Charlie Kaufman for the filmmaker’s metatheatrical play “Synecdoche, New York.”

The 2008 film centers on a theater director eager to celebrate the mundanity of real experiences. The only way he knows how to do that is to put on a show of his own life and the lives of everyone he comes into contact with. “I’m just a little person,” Martine sings. “One person in a sea of many little people who aren’t aware of me.”

“I feel like that’s the case with everyone in New York,” she says. “And with everyone in ‘Ghosts,’ too. You have everything, everywhere, at the same time, in the TikTok universe, where every story is simultaneous. Where everyone is the protagonist of their own narrative. Which is as close to reality as you can get.”