I've always been obsessed with gothic. Whether it is Edward Gorey's children who are smothered on peaches, sucked by leeches or smothered by rugs; Du Maurier's heroines in danger or the disturbing erotic power of Angela Carter's fairy tales, the gothic world has always had me in its clutches. It is a genre where comedy and horror, repulsion and desire, sex and death are always intertwined, where every exchange is fraught with threats of violence, sex, or both.

With “Saltburn” I wanted to write a gothic story or, more specifically, a story that was inspired by the literary subgenre of English rustic gothic. “Rebecca,” “Brideshead Revisited,” “The Go-Between”—these stories are so familiar, the rhythms so reassuringly consistent, that we know where we are the moment the wrought-iron gates open, or at least we think. to do. I like familiar stories: I like the squeak they make when you squeeze them really hard.

In this family story, there is always a first-person narrator, absorbed by a world beyond his understanding. A framed narrative in which this person remembers a time that completely froze her life, that left her trapped, always reviewing every detail, trying to make sense of everything. There are also familiar characters: the innocent bystander, the doomed romantic hero, the desperate sister, the jealous rival, the all-seeing butler, and the house itself, which is inescapably the main character, never changing and impervious to the people who live it. in that.

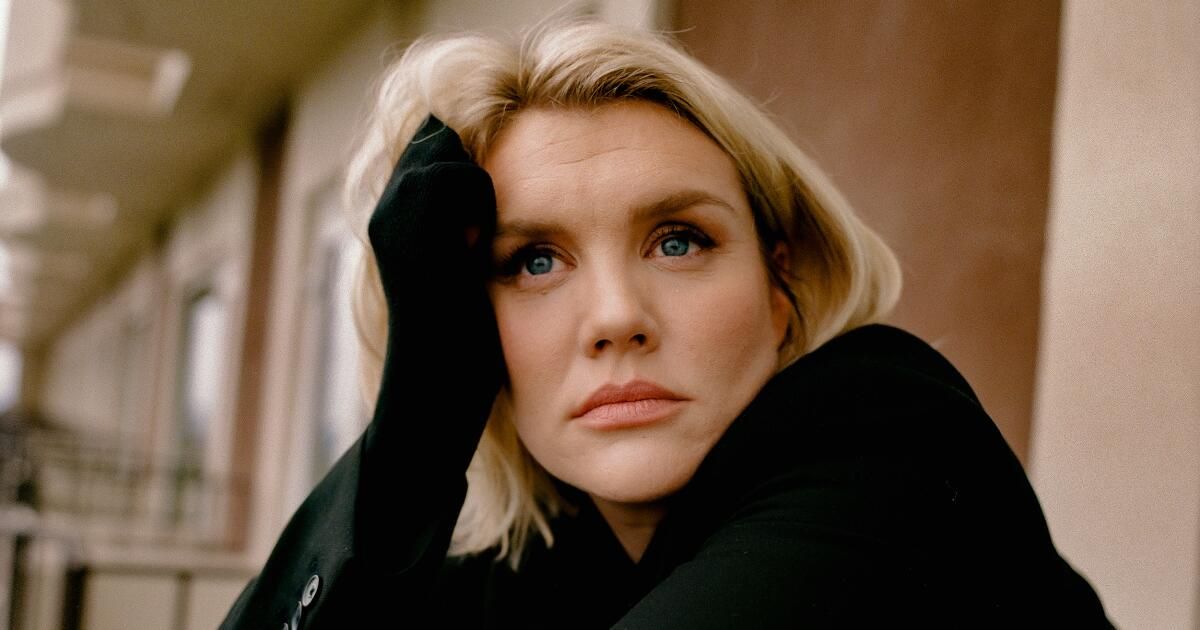

“'Saltburn,' like many of the books and movies that precede it, is a story about restraint and its limits, and what happens after they finally disappear,” writer-director Emerald Fennell says in an essay.

(Amazon Studios)

In this case, that house is Saltburn, and its residents are the Catton family, who absorb the innocent Oliver Quick into their fantasy life during the summer of 2007.

It makes sense to me now that “Saltburn” is a project I finished writing during the lockdown of a global pandemic, a time when we were all forced into the position of permanent voyeurs, where parasocial relationships became all-consuming. There was nothing to do but observe, poring over the details of other people's lives, their homes, their clothes, their food, their families.

The intimacy we learned with these strangers was surprising, unprecedented, and completely one-sided. The beautiful strangers never looked back, how could they? For a long time, these powerful imaginary friendships, which inevitably lead to self-loathing, jealousy and a sadomasochistic inability to look away, replaced all human contact.

It was the very definition of “look but don't touch.” We weren't allowed to be in a room together, much less exchange the kind of fluids that humans need to exchange not only to enjoy but to survive. What did this do to us? What happens to someone when they can't touch what they want to touch so much? Perhaps something similar to the gothic madness that consumes Oliver.

After so much isolation, I wanted to write something to be seen in a dark room with strangers. Something created for the specific and disturbing intimacy of the theater. Something that would make the audience aware of the person sitting next to them, that could provoke a visceral physical response: the kind of interaction, the sticky pleasure that we had all been denied.

“Saltburn,” like many of the books and movies that precede it, is a story about restraint and its limits and what happens after they finally disappear. What will happen when the woman locked in the attic finally frees herself?

She burns the house down.