On Oct. 26, 1970, the night Muhammad Ali made his comeback fight in Atlanta against Jerry Quarry, a houseful of party guests, including some heavyweights from the organized crime world, were robbed at a suburban after-party — a story that made a lot of waves at the time and was recently the subject of a true-crime podcast, “Fight Night.” Now, Shaye Ogbonna (“The Chi”) has translated it into a wildly varied concoction of a limited series, “Fight Night: The Million Dollar Heist,” premiering Thursday on Peacock, with an all-star cast in the not-exactly-real-life lead roles.

Kevin Hart plays Gordon Williams, known as the Chicken Man (not to be confused with the Chicken Man who explodes in Philadelphia in Bruce Springsteen’s “Atlantic City”) for his habit of buying chicken sandwiches for pretty girls. Williams (whom I’ll call Williams because I don’t want to keep writing “Chicken Man”) is a self-described hustler, who makes his living mostly on numbers, the unofficial downtown lottery. He’s a beloved and popular figure in the neighborhood (he is comedian Kevin Hart, after all), except to the people he owes money to.

When a close friend, Silky Brown (Atkins Estimond), mentions that New York’s “Black Godfather,” Frank Moten (Samuel L. Jackson), will be in town for the fight, Williams, hoping to become Moten’s right-hand man in Atlanta, convinces him to throw Moten and other crime bigwigs (most notably New Jersey bigwig Cadillac Richie (Terrence Howard)) a casino-style party at his house – the house he shares with his girlfriend, Vivian (Taraji P. Henson), rather than the one he shares with his wife, Faye (Artrece Johnson), and their children. Some evil villains get wind of this and plan to rob everyone at the party.

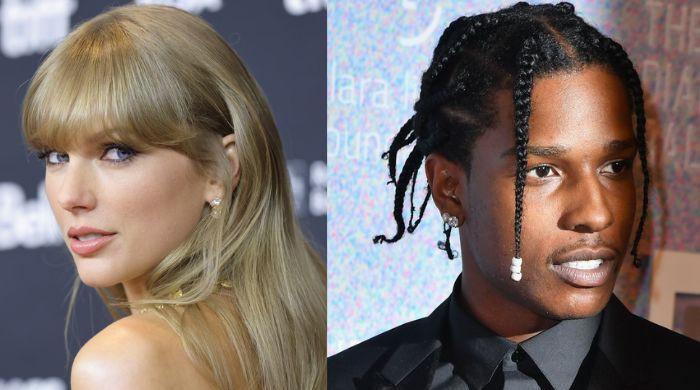

“Fight Night” stars Terrence Howard as Cadillac Richie, Samuel L. Jackson as Frank Moten and Michael James Shaw as Lamar.

(Parrish Lewis / Peacock)

Although much of what precedes and follows this event is fabricated, the mechanics of the robbery, as depicted in the footage, are fairly consistent with established facts: armed, masked men escort arriving guests directly to the basement, where they are stripped of their valuables and clothing. Estimates of the loot (estimates only, because all but a few of the guests were reluctant to talk or press charges) amounted to around $1 million, a conveniently round and impressive figure, suitable for a miniseries subtitle. As the owner of the house, Williams, though a victim himself, was singled out in the press as the prime suspect, with a target painted on his back.

Meanwhile, cop J.D. Hudson (Don Cheadle), Atlanta’s first black detective lieutenant, is assigned to protect the controversial Ali (Dexter Darden, a couple of inches shorter than the champ but fit for the role in every other way), doubly a target for refusing to be drafted and for being black in a state where the Klan is active. (Segregationist Gov. Lester Maddox will make a strange, unbelievable, and certainly historically inaccurate appearance on a lonely country road as Hudson is flying Ali to his plane out of town.)

A related issue — not enough to constitute a theme, but one that permeates the series in a way that reminds us of its presence — involves the future of Atlanta, characterized as a rural city destined to become a center of black wealth and power.

In this story, protecting Ali starts out as an unpleasant job for Hudson, a veteran who thinks Ali should have served. (“Honey, you served in Missouri,” his wife, Delores, played by Marsha Stephanie Blake, reminds him.) He obliviously addresses Ali as Mr. Clay, who in turn calls him “Officer Mayberry,” and their antagonism provides a platform for commentary on race in America. But as they spend time together, before Ali departs the series in the third episode of eight, a mutual appreciation grows. This could be the basis for a sweet little standalone movie (it’s certainly the series’ most heartwarming passage), but in context, it’s a prelude to the action movie waiting in the wings.

With Ali gone, Hudson is given the assignment to investigate the burglary at Williams' home. As a black man, it is thought he might have better luck with witnesses. Fellow black lieutenant J.H. Amos, his partner in the actual investigation, has disappeared from the narrative. In his place, we have a competitive, violent, racist white cop (Ben VanderMey) whom Hudson is determined to bring down.

Don Cheadle plays upright and honest cop JD Hudson.

(Eli Joshua Adé / Peacock)

The retro credits, split-screen effects and period R&B songs suggest something light-hearted from the start, but much of the film is very dark: there are lots of guns, which are waved around, pointed at heads and often fired. Most of the characters are criminals, from the semi-comic and relatively harmless Williams to the deceptively urbane Moten and the merely thugs, although there is an attempt to delineate the worst and least worst among the thieves and in some cases even to elicit viewer sympathy.

But this is no “Ocean’s 11” or “The Thomas Crown Affair,” despite its generous use of late-’60s and early-’70s visual tropes. “Fight Night” flirts with a variety of styles — blaxploitation, police procedural, social drama, buddy-cop movies — that succeed on their own terms but don’t easily cohere. And as the series nears its conclusion, the plot veers further and further from the facts, sacrificing historicity and even verisimilitude for the sake of genre-movie thrills and culminating with a stinger that catapults things out of the real and into the ridiculous.

Any project that brings Cheadle, Jackson, Henson, Howard and Hart together in one place is going to be worthwhile, no matter how successful or unsuccessful it is overall, and they can all give a top-notch performance. In fact, at times it seems like the scenes have been designed precisely for that purpose, with almost theatrical monologues that give the actors room to stretch out. Anything less than that would seem… inhospitable, like locking them in a basement.