Augusto Góngora did not remember how long he and Paulina Urrutia had been together, nor the exact chronology of their shared years. However, what he never forgot was how much he loved her. That feeling remained intact despite her battle with Alzheimer's disease.

Therein lies the heartbreaking luminosity of Chilean director Maite Alberdi's Oscar-nominated documentary, “Eternal Memory,” which chronicles their unconditional adoration for each other in the midst of their illness. The cosmic irony of Góngora's condition, Alberdi initially thought, is that for decades he acted as guardian of the country's historical memory.

As a journalist during the atrocious Pinochet dictatorship, Góngora was behind clandestine news programs and then, when democracy returned, he produced cultural programs for public television. Urrutia, on the other hand, is an accomplished actor with credits on stage and screen and former minister of Chile's National Council of Culture and the Arts.

Alberdi had long admired their respective careers, but after Góngora publicly revealed details about his deteriorating health, the filmmaker witnessed Urrutia bring him closer to others as part of his theater rehearsals, rather than isolating him.

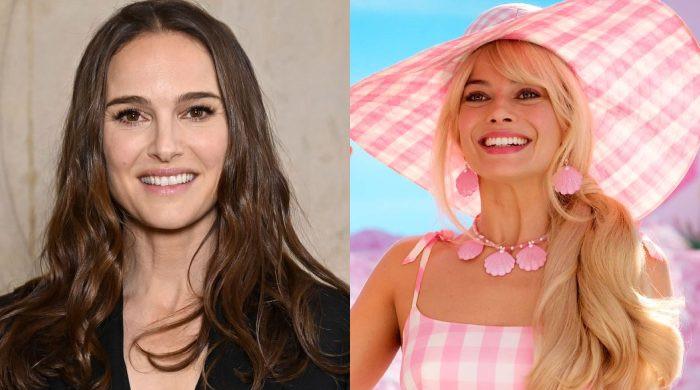

Maite Alberdi, director of the documentary “La Eterna Memoria”.

(Micromundo Productions)

“It immediately caught my attention because it was the first time I saw a person with dementia so integrated into the world and I felt that this was the way to understand caring for someone,” Alberdi said of her initial interest. “I saw a very loving and active relationship.”

Without hesitation, Góngora agreed to Alberdi's proposal to make a documentary. He defended the project to Urrutia, who was understandably more reluctant to expose his privacy. His reasoning boiled down to honoring the people who had trusted and shown his pain to his camera. How could he not agree to show his own fragility now?

The first two years, Alberdi recalled, consisted of gradually seeing how comfortable his subjects were filming and building trust. That both Góngora and Urrutia were used to being in front of the camera given their professions facilitated that process.

When the COVID-19 pandemic prevented Alberdi from physically visiting the couple, he sent Urrutia a camera.

Although Alberdi had taught Urrutia how to use cameras, most of what the actor filmed was out of focus. Despite the lack of technical mastery, the scenes were moving, which served as a lesson to the director that “the most important thing is emotion.”

“That's how the story became a choral piece because it has images from Augusto's camera from 20 years ago, in addition to mine and Paulina's,” Alberdi said. “It's the three of us taking different chunks of time to build a common relationship.”

Alberdi was filming for four and a half years without knowing how the doc would end. Then one day, while they were filming, Góngora looked at Urrutia and said: “It's not me anymore.”

“That day was the first time I felt uncomfortable filming because he was uncomfortable with himself. Before, although he had Alzheimer's, it seemed that he felt his identity and I also saw it very present,” said Alberdi. “The loss of identity was the limit for me.”

For Alberdi, “Eternal Memory” is as much about this lasting romance as it is about Chile's past. When making the heartbreaking dual portrait of him, Alberdi realized that Góngora had not forgotten everything he investigated, but that he could only remember it viscerally.

“He couldn't tell you what year the dictatorship began, but he could tell his painful memories of what happened until the last day,” Alberdi said. “And what that tells you is that there is a historical emotional memory that remains as time passes, no matter how much specific dates or events are forgotten.”

Alberdi believes this notion is crucial to fighting the far-right ideologies that have emerged in Chile and around the world, 50 years after the coup that put Pinochet in power.

These reactionary forces may try to manipulate or erase the facts – practicing historical denialism and reinterpreting human rights violations – but they will never be able to erase the country's indelible pain.

In retrospect, Urrutia is now grateful that Góngora, who died in 2023, made a decision and convinced her to make the film. Talking about him has helped her grieving process.

“She thought her story was very local, but then she realized that it was not the story of a country, but the story of a love and a story of memories,” Alberdi said.