On the shelf

Runaway train

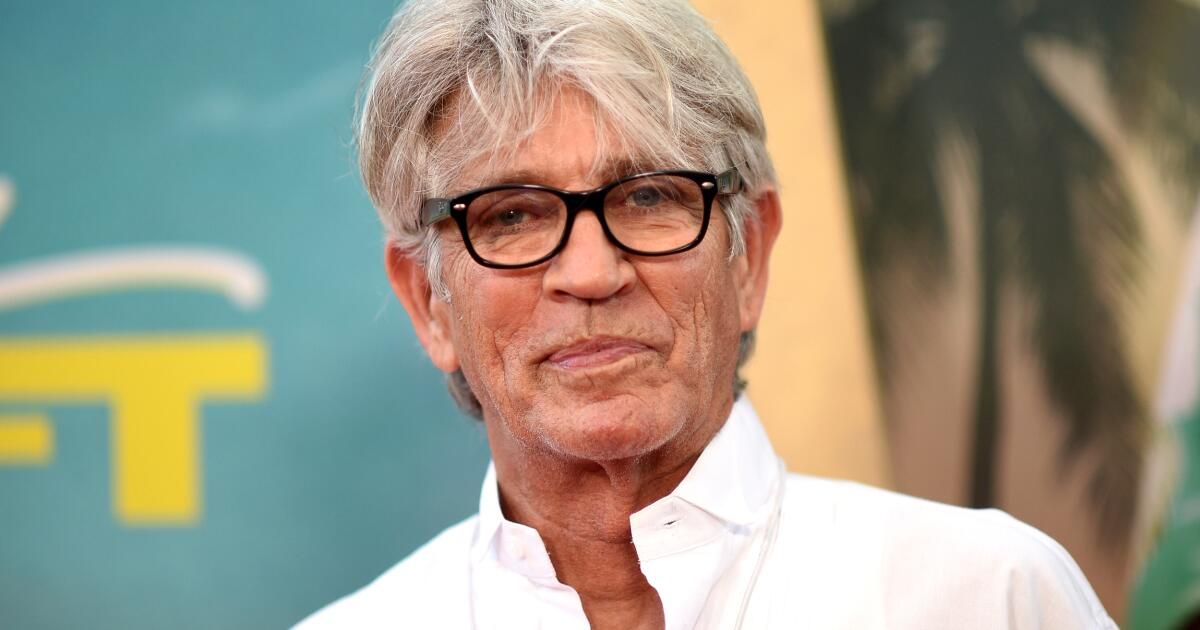

By Eric Roberts

St. Martin's Press: 304 pages, $30

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission. Librería.orgwhose rates support independent bookstores.

The entertainment industry is facing an existential crisis, with less content to produce and far fewer jobs available. Fortunately, Eric Roberts realised this situation long before anyone else, even before we made a living watching TV series as a point of pride. “Now you don’t get time to rehearse and you get paid less,” says Roberts, known for his fast-paced films. “You can’t just sit around waiting for the big paycheck to come in anymore.”

As Roberts writes in her new memoir, Runaway Train: Or, the Story of My Life So Far, which is out now, she entered this new normal years before everyone else was scrambling for scarce jobs. Roberts feels the rush, too, which is why she “says yes to everything.” “We’re often in the red, broke and scared. I know people who were in the cast of ‘Titanic.’” [who] “They can’t pay the rent,” Roberts writes in his memoirs.

But Roberts no longer wants fame; he just wants to work. In the book, which Roberts wrote with journalist and novelist Sam Kashner, he boasts 750 credits on his IMDb page. By the time he sat down for this interview in August, that list of credits had grown to nearly 850. “I’m an actor, first and foremost,” he says. “Everything else is secondary.”

Roberts, prominent among a generation of New York stage actors who turned to film in the 1970s, burst into the public consciousness in Bob Fosse’s 1983 biopic “Star 80” as Paul Snider, the homicidal husband of Playboy Playmate Dorothy Stratten (played by Mariel Hemingway). Roberts doubled as his character, a manipulative, small-time con man whose self-loathing turns into murderous rage.

Other high-profile roles followed, including that of fugitive Buck McGeehy in Andrei Konchalovsky’s 1985 action thriller “Runaway Train.” The actor received an Oscar nomination for that role, which landed him on talk show couches and tabloid covers. Rich and feeling like himself, Roberts bought a penthouse on Manhattan’s Upper East Side and a house in Greenwich, Connecticut. He also began abusing cocaine. He would eventually lose the apartment and the house; the drugs remained.

But the book “Runaway Train” is not a tearful atonement for past sins, a Hollywood comeback work designed to jumpstart a once-popular career. Roberts is well aware that she has made horrible choices, that her erratic behavior damaged her relationships with friends and family, including her sister Julia Roberts (their relationship remains rocky; Roberts claims that “we have agreed not to talk about each other’s careers”). Still, Hollywood lore is littered with addicts who have thrived despite their bad habits, and for a time, Roberts walked a tightrope.

As Roberts describes in embarrassing detail in the book, his fall from grace came slowly, then suddenly. He always managed to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, and refused roles with Quentin Tarantino and Oliver Stone, among others. “I was high when I auditioned with Ron Howard,” Roberts says.

Roberts was an erratic maniac, to be sure, but much of what he learned about the dark arts of self-immolation was taught to him by his father, Walter, a screenwriter during the glory days of radio theater who later opened his own theater in Atlanta, where Roberts was raised. Walter, a bitter and arrogant struggler, encouraged his son to act, only to fiercely criticize him when he did, which confused and infuriated his son.

Roberts’ father was a small-time hustler and once tried to enlist him to rob a drugstore for urgently needed money. At night, Roberts’ mother frequently beat him with a stake. The blessed relief from the lashing of the stake came when Roberts’ parents separated. Walter gained custody of Roberts; his sisters Julia and Lisa went to live with their mother. Walter continued to cut his son down. “My father taught me a lot about the process of being a professional actor, but he belittled me at every turn,” Roberts says. “As a kid, it was very difficult. How do you deal with a parent like that? It was hard to process.”

Even when Roberts managed to scrape together the money to move to New York, his father continued to harass him with an endless stream of letters in which he alternately bullied him by calling him mediocre, praised his talent, asked for money and accused him of abandonment. “I kept getting thousands of letters,” Roberts says. “I still get them. It was crazy, man! Over time, I realized that you have to love people for who they are, but you can’t let them walk all over you. Even when he was sincere and loving, it seemed out of place and petty.”

Despite this epistolary “mind control,” Roberts soldiered on and landed her first television job in 1977 on the soap opera “Another World.” Roberts’ fiery, dazzling intensity caught the eye of Joe Papp, a New York theater panjandrum who cast Roberts in a Public Theater production of the Civil War drama “Rebel Women.” Roberts earned her Actors’ Equity card and then landed her first film role as Dave Stepanowicz, the scion of a New York crime family, in 1978’s “King of the Gypsies.”

Yet while Roberts was endearing herself to a wider audience, she was infuriating directors with her insistence on staying in character 24/7. “I would yell at people for no reason, lock myself in my trailer and violently kick the door from the inside,” Roberts writes of “Star 80.” “I began to protest [Snider] to the point of endangering the entire production and infuriating Fosse.”

After that, it was hard to shake the “problem actor” label, especially considering the impulsive eccentricities he so convincingly displayed on film. Roberts’ drug addiction didn’t help his cause much. “There was cocaine everywhere,” he says. “I mean, if you go to the prop truck on a set, they have a big bowl of cocaine for everyone. How could I possibly get any work done?”

“I don’t really know how I got on with all this,” says Eric Roberts. “If it hadn’t been for my wife, I might be dead by now. I know it sounds dramatic, but it’s a fact.”

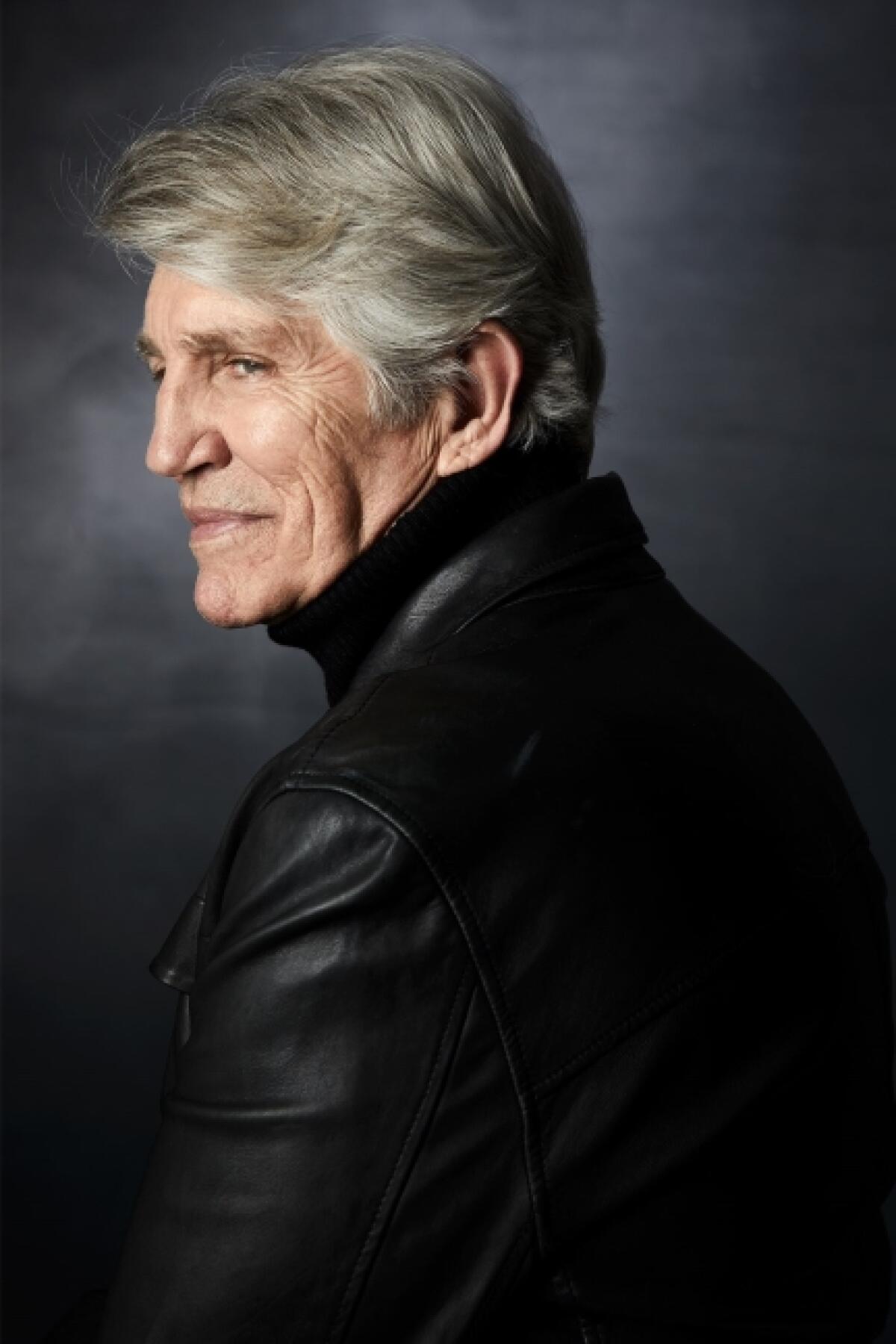

(Photography by Deborah Feingold)

Roberts' private and public lives converged, as if he were using Stanislavski's sensory memory in reverse, conjuring up strange scenes from his films as material for his own personal use. His stepson Keaton, whom Eric helped raise, left home as a teenager, bewildered by Roberts' erratic and often violent behavior. In 1995, Roberts was arrested for pushing his wife Eliza against a wall.

Suffice it to say that he didn't walk into rehab; a court order put him there, for 18 months.

When he emerged, somewhat liberated from his own self-loathing, Eliza was waiting for him. She picked him up, ignored him and ushered him into a life in which he would sublimate his addictive impulses into a steady job. She is Roberts’ manager and consigliere, and the relationship has paid off. This year alone, Roberts has acted in 73 productions: a Western miniseries, some low-budget sci-fi films and something called “My Redneck Neighbor: Chapter 1 — The Rednecks Are Coming.” He is also a contestant on the new season of “Dancing With the Stars,” which premieres Tuesday.

And Keaton is back. A singer, songwriter and film and television music composer, he has subsequently worked with Roberts. As for Emma, Roberts' daughter with ex-partner Kelly Cunningham, Roberts says that, considering they have not been involved in each other's lives and don't communicate with each other as much, their relationship is “cordial and supportive, but not close.”

Roberts, who has tried to sabotage his life and career many times, is aware that the opposite could have happened. “I’m not really sure how it turned out for me,” he says. “If it hadn’t been for my wife, I might be dead by now. I know it sounds dramatic, but it’s a fact.”

Eric Roberts will be signing copies of his memoir, “Runaway Train,” at 7 p.m. on September 25 at Barnes & Noble At the Grove in Los Angeles