Why am I so fascinated by Elizabeth Taylor? My admiration for her work stems, perhaps unusually, from Zeffirelli and Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew and Nichols and Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, two films in which she starred alongside her then-husband, Richard Burton. And I must have seen her in some of the Father of the Bride movies (the original ones, with Spencer Tracy, not Steve Martin) when they came out on television, because I watched almost every comedy that was on TV. But the adult dramas she did, like Butterfield 8, Raintree County, and A Place in the Sun, weren't so much to my taste back then, and I'm not sure I ever saw her in her breakout roles as a child actress in Lassie Come Home and National Velvet.

And yet, like any American who lived through the second half of the 20th century, I was aware of her much-photographed face, her pervasive presence in the press, which ranged from the respectable and deferential to the sensational and salacious. There were her numerous marriages (two of them to Burton, most famously), her fabulous jewelry, the enormity of “Cleopatra,” the first movie for which an actor was paid a million dollars, and whose cost overruns and commercial failure nearly bankrupted the studio. Andy Warhol painted her even before he got to Marilyn Monroe. Later, there were ads for her fragrance line and her pioneering philanthropy in AIDS research.

Elizabeth Taylor as a child.

(Elizabeth Taylor's estate / HBO)

And so we come to “Elizabeth Taylor: The Lost Tapes,” a stylish documentary from Nanette Burstein (“Hillary,” “The Kid Stays in the Picture”). Premiering Saturday at 8 p.m. on HBO and streaming on Max, the documentary builds on 40 hours of “newly discovered” interviews recorded beginning in 1964 by journalist Richard Meryman for a potential book. Taylor was only 32, but had already been making movies for 22 years and a star for 20. It is her voice that drives the narrative, aided, in small but significant ways, by close friends and associates, including Roddy McDowall, her “Lassie Come Home” co-star and longtime confidante, and Debbie Reynolds, who became less of a close friend after her husband, Eddie Fisher, suddenly became Taylor’s husband. A wealth of archival film and newsreel material, home movies and snapshots—and, for context, new images of tape recorders, ashtrays, and martini glasses—provide a wonderful illustration of Taylor's work and world.

Of course, we have an abiding interest in the private lives of public figures — not necessarily the dirty laundry, though careers have been founded on unearthing and publishing it, but in understanding the everyday life of extraordinary talent, in finding the human being in figures — I think I can use the word “iconic” here — who seem beyond ken. Taylor’s initial public persona was created by studio publicists, who sent her on fake dates simply to make her seem like an ordinary teenager, but she was also one of the first celebrities for whom that narrative spiraled out of control. Taylor was labeled a “homewrecker” after “stealing” Fisher from Reynolds; she married him, she says, because she could talk to him about his best friend, her late husband Mike Todd, who died in a plane crash. But it was when she began an affair with Burton, while they were making “Cleopatra,” that paparazzi culture kicked into high gear.

Today, under the scrutiny of 10,000 cell phones and the constant pressure to promote themselves, celebrities are more likely to show a little dirty laundry, let you into their homes, or sit down for “revealing” interviews with interviewers whose celebrity is equal to their own. But they are revealing only within certain limits. Because these conversations were recorded as deep background over many hours, and not one or two hours of conversation to be immediately channeled into a magazine article, there is a certain expansive, spontaneous informality to them, especially when McDowall is in the room and participating. One would have liked to have had something like that from Elvis Presley or Marilyn Monroe.

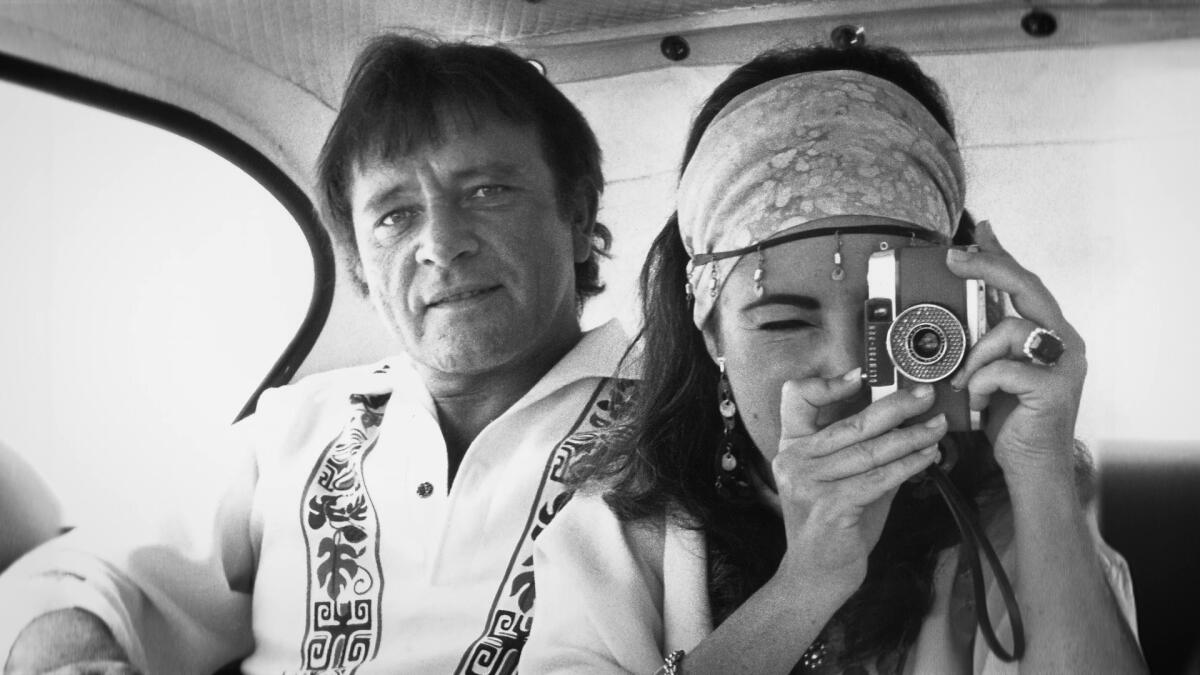

Richard Burton with Elizabeth Taylor. They were married and divorced twice.

(Elizabeth Taylor's estate/HBO)

What is a revelation, watching thematically selected clips from her films (a small sample of a filmography in which the word “substantial” barely does justice), is what a good actress she was, and how reactive. Burton said (and he himself often repeats) that when he first acted with her on the set he thought she was no good, but when he saw the dailies he was astonished, and it is true that she is wonderfully, intensely alive in the film. If you are not paying attention, it can be hard to see her, through the capital S of Stardom and the distraction of her features: “It was really like an eclipse of the sun: it blotted out everyone in the office,” says MGM producer Sam Marx, for whom one look was enough to cast her, without audition, in “Lassie Come Home” and the irresistible temptation to play up her looks: “She is 5’5” and 110 pounds of glorious 16-year-old cover-girl beauty,” as an early promotional clip describes her. And many of his films, it must be said, did not live up to his talent.

That tension between the public and the personal, between trash and art, is the backbone of the film. Taylor hated being “a public service. I didn’t like fame, I didn’t like the feeling of belonging to the public; I liked being an actress or trying to be an actress.” At the same time, she could feel insecure about her acting, especially when she was paired with method actors (and good friends) like Montgomery Clift and James Dean. Of her own method, she says, “It’s not technique, it’s instinct.” And yet everything she did worked.

This is neither a complete account of Taylor’s career nor a journalistic incitement to delve into it, though she herself is quite good at it (we learn that she likes men who can dominate her; she would annoy Todd just so she could lose the ensuing argument). All the narrators are, to be sure, at least a little unreliable, both as to historical facts and internal states, and “The Lost Tapes” is, of course, limited by the fact that the tapes run out when Taylor is in her early thirties; the rest of the story, much condensed, is continued by others. But on the whole, Burstein’s film feels big and perceptive, a love letter to an extraordinary, interesting, and very human human being.