India Donaldson stopped acting when she was about 7. In fact, it’s one of her earliest memories. Her father, veteran Hollywood director Roger Donaldson, asked her to be an extra in a restaurant scene for his 1994 film “The Getaway,” co-starring newlyweds Alec Baldwin and Kim Basinger. Other kids might have been thrilled. She was mortified.

“My older brother had a line, and in my memory, he was really thriving in that context, but I was kind of embarrassed,” India Donaldson says over Zoom from Los Angeles, laughing at her younger self. “I had a bowl of Cheerios and I was eating them, and I remember my dad coming over and whispering, ‘You don’t actually have to eat Cheerios. ’” eat “The Cheerios.”

She shakes her head. “I never acted in a movie again.”

Though acting wasn’t in her future, Donaldson, 39, has emerged as a formidable filmmaker, following in her father’s footsteps with the release of her first feature, “Good One.” Hailed at Sundance and invited to screen at the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, the intimate drama consolidates the strengths of several previous short films, demonstrating her ability to create delicate worlds in which ordinary people navigate — if not always comfortably. It’s the story of a daughter and father, teenager Sam (Lily Collias) and Chris (James Le Gros), a remarried divorcee, on a weekend camping trip in the Catskills with Matt (Danny McCarthy), an old friend of Chris’s. Sam and Chris love their escapes into the wilderness, but this particular excursion will be one that stays with the 17-year-old for the rest of her life. She just doesn’t know it yet.

Lily Collias in the movie “Good One”.

(Images from Metrograph)

It would be a stretch to say that the process of making “Good One,” which opens Friday, began at the Getaway restaurant. But to get to the point where Donaldson finally felt ready to be a writer and director, she would have to draw on her own life as the daughter of a successful filmmaker. “Good One” is not autobiographical, but it is deeply personal.

“I think it was more a product of the evolution of the person I am,” he says. “It took me a while to have the confidence to imagine myself in a role where you ask people – your collaborators, the people who give you money – to trust you.”

In another telephone interview, Roger Donaldson, who began his career in the late 1970s in New Zealand and Australia with films like “Sleeping Dogs” before moving to the U.S. to make studio pictures like “No Way Out,” “Cocktail” and “Species,” practically beams as he talks about India.

“She designed and made clothes and toys and wrote stories that indicated she had a talent for doing creative things,” he says. “The first indication of her interest in film [was] “She studied creative writing. She was always a very creative writer, but she kept it pretty much a secret until she made those short films.”

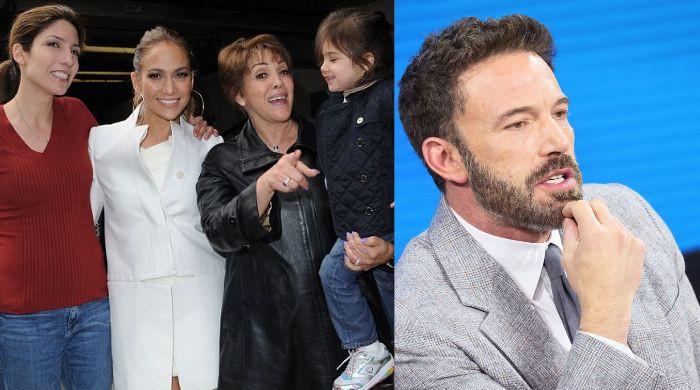

India Donaldson and producer Graham Mason on the set of “Good One.”

(Eric Ruby)

India was not one of those rebellious teenagers. “I idolized my parents and wanted their approval,” she says, a little sheepishly, noting that Roger and her mother, Mel Clark, divorced when she was young. “My mother is a very creative person. She’s an incredible designer. She had a knitwear line when I was a kid and then she had a yarn store in Santa Monica when I was in high school—she was always making stuff.”

But while other children of famous directors might consider filmmaking their birthright, India, as her subdued personality indicates, didn’t feel entitled to it. In conversation, she exudes a down-to-earth, nerdy best friend vibe. Despite having grown up in Hollywood, there’s nothing polished or cool about her, just a slightly studious air. India had been fascinated by movies since childhood — she remembers watching dailies with her father, trying to spot slight differences from shot to shot — but thought the work was beyond her capabilities.

“I had to go a bit further to get to that point,” he says. “As a teenager, I was a more introspective person and I identified directing as an outside job. I don’t think that’s true now, but it was an idea I had that I had to prove wrong through my own experience.”

Watch his three short films: “Jellyfish,” “The Hannahs” and “If found,” All available on YouTube, and you’ll get a glimpse of the low-key, observant style he brings to “Good One,” which captures the still-bitter male rivalry between middle-aged friends. “There’s a kind of passive way in which the characters express themselves, a subtle passive aggression,” he says when discussing what connects his shorts to his feature. “I think that’s always fascinating, the ways in which human beings act in ways that are adjacent to what they want to say or what they want to do, the indirect ways in which we get to where we want to go.”

James Le Gros, right, and Danny McCarthy in the film “Good One.”

(Images from Metrograph)

Had the pandemic not happened, Donaldson might not have found the right headspace to dream up “Good One.” After growing up mostly in Los Angeles and attending Santa Monica High School, she attended Vassar College and lived in New York for 10 years. Then, in March 2020, just before the world changed, she and her husband moved back west for a job she’d landed in a writers’ room for a show that never got made. But once lockdown took hold, they impulsively moved in with Roger, his third wife Marliese, and India’s two teenage half-siblings, Will and Octavia. Being around family, especially the teenagers, gave Donaldson the first impulses for the script she would write.

“I think these characters and their dynamics had been brewing in an abstract way for some time,” he recalls. “I was reflecting on my youth through [my half siblings] and my proximity to them. The circumstances of the world at that time placed these characters in this particular environment.”

The title “Good One” is derived from the idea that Sam is the golden child, the good one. This poised, mature-for-her-age young woman enjoys spending time with her father, despite being at an age when most children don’t, and converses easily with both men. But it also references Donaldson’s conflicted feelings about their similar status in their blended family.

“Everyone in my family can see themselves as the person trying to keep the peace, because that’s probably what we were all trying to accomplish,” she says. “But I can also point to specific memories of things like, ‘Well, my dad likes to take pictures,’ so I’m going to be the one who’s like, ‘Yeah, I’ll go out with you and you can teach me how to use a camera. ’ Adapting your interests to your parents so you can be close to them — I think that’s how our personalities are formed in a lot of ways.”

Both Donaldson and his father, who have gone on numerous camping trips together, stress that “Good One” does not reflect actual events. That caveat may seem unnecessary for most of the film’s running time, which consists of the three characters hiking and hanging out. But slowly, a quiet tension builds, leading to a haunting moment that happens so quickly and so casually that some viewers may wonder if what they saw really happened. It irrevocably changes how the audience feels about Sam and these men.

Donaldson says the story's brief but profound impact was something that occurred to him early in the project's genesis.

“I wanted to explore the idea that we will inevitably be disappointed by our parents,” explains the director, who is the mother of a three-year-old. “Those of us who become parents will disappoint our children in ways we can’t foresee, even when we do our best. Somehow, despite all that confusion, there is a relationship to be maintained.”

Her relationship with her father has grown even stronger since she became a mother and director. On the film front, Roger offered his daughter practical advice that he emailed to her (one small detail: “If you haven’t finished the scene and the sun has set and the director of photography says, ‘That’s it, I can’t shoot any more,’ you just say, ‘No, we’re still shooting. ’”). But he resists the suggestion that he deserves any credit for the success of “Good One.”

“I think she appreciated that I took the trouble to give her my take on the trials and tribulations of being a film director,” he says modestly. “But you’re out there on your own, you have to deliver the goods yourself.” He marvels at how India has come to be what she is. “That didn’t happen overnight. As a teenager, she was…”

She pauses, trying to find a way to describe her daughter. “‘Overpowered’ isn’t the right word. She just worked hard and gave it her all. She wasn’t flamboyant or in the spotlight. But she got noticed because everything she did, she did so well.”

James Le Gros and Lily Collias in the film “Good One”.

(Images from Metrograph)

India Donaldson cites Kelly Reichardt as one of her main influences, and indeed, “Good One” echoes the sensitive, skeletal drama of “Old Joy,” another Reichardt film about men in the woods. Though “Good One” chronicles a tense vacation, she has only good feelings about her childhood camping trips. “My father loved to just get away, and that’s part of the spirit that inspired this film,” she says. “He loves to let your thoughts wander and take distance from your everyday life. I had a lot of those experiences with him growing up that seemed instrumental in making space for yourself to be a human being outside of an industry.”

The wisdom in Donaldson’s debut is uncommon, and it resonates with something broader about masculinity, family, and letting go of childhood stories about oneself and one’s fathers. It’s not exactly a confession, but once you know more about its creator, the clearer it becomes how much the film reveals about her, especially when she reflects on the similarities she’s discovered between fatherhood and filmmaking.

“You can’t control how people are going to feel about it, what their life will be like in the world without you,” he says, smiling, referring to both a movie and a child. “You just do the best you can and hope you’ve given them the tools to thrive.”