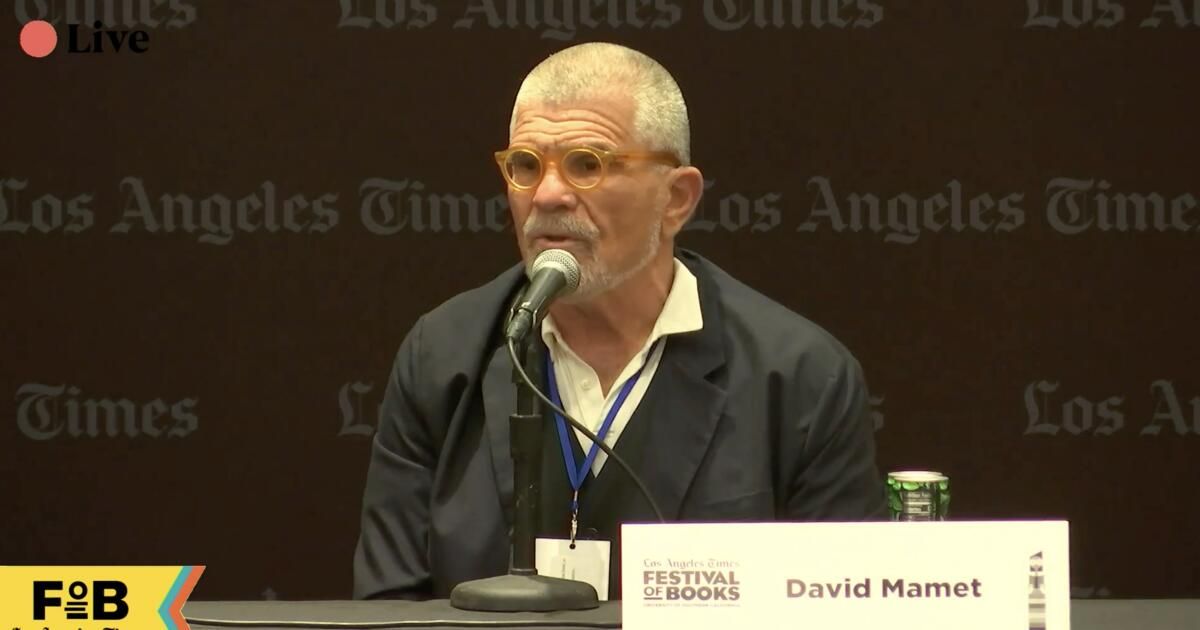

David Mamet is not done criticizing the liberal Hollywood establishment.

“DEI is garbage,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning author told a packed house at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books. “It is fascist totalitarianism.”

The playwright and director didn't shy away from his trademark expletives and controversy while discussing his revealing memoir, “Everywhere an Oink Oink,” with Times deputy entertainment editor Matt Brennan at USC's Newman Recital Hall.

His book, published this fall, details his last 40 years in the movie business and his fall from grace as his politics transformed him from a progressive “red diaper baby” of two communist Jewish parents raised on Chicago's South Side to a current Trump-loving conservative.

For more than a decade, Mamet's political and social statements have made as many headlines as his film and theater work. Her latest complaint is with new diversity rules the Film Academy instituted for Oscar-eligible films to help advance representation of LGBTQ+, women, ethnic minorities, and disabled people.

The idea that “I can't give you a stupid statue unless you have 7% of this, 8% of that… is intrusive,” Mamet said.

Although Mamet acknowledged that discrimination kept groups from participating in Hollywood for years, he believes the pendulum has swung too far in the opposite direction. In his book, Mamet describes the leaders of these diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives as “diversity kingpins” and “diversity commissioners.”

“He [film industry] It doesn’t have much to do to improve everyone’s racial understanding, just like the fire department,” Mamet said, drawing some laughter from the crowd. He maintained that his colleagues are better off selling popcorn than trying to improve the representation of women, queer talent, and other marginalized groups.

Mamet did not mince his words. He used the outdated term “transsexuals” when he talked about transgender people and criticized gender-neutral bathrooms. “This politicizes the human excretory function,” he said to even louder laughter from the crowd.

He proudly asserted his defense of free speech in an amicus brief he wrote to the Supreme Court this year in NetChoice LLC v. Paxton. “We see major attacks on freedom of expression in this country,” Mamet said.

Film executives and writers were also not safe from Mamet's criticism. He blamed movie studios for the “hegemony” that has stifled the voices of independent filmmakers. “There is no room for individual initiative,” Mamet said. He added that the film industry is experiencing the “growth, maturity, decay and death” that “happens to everything that is organic.”

In 2007, Mamet openly opposed the writers' strike and complained last year when writers reached an impasse with studios while negotiating pay increases and protections against the use of artificial intelligence.

“There will be less work,” Mamet admitted. “But the scripts will be better.”

Does Mamet consider his children to be nepo babies who have benefited from his illustrious career? Not at all, she said. He feels satisfied that they learned from being on set with him.

“They earned it on merit,” he said of his daughter Zosia Mamet, who starred in “Girls.” They haven't benefited from any kind of privilege, she said, and she believes DEI initiatives are taking away from hard-earned opportunities. “No one gave my children jobs because of their relationship.”

Mamet said he has been pushed out of Hollywood less because of his politics than because of his age. Young directors want to work with friends from their own generation.

“No one is going to pay me much money anymore,” Mamet said. “No one will let me have much fun.”