It would be hard to imagine a genre more antithetical to Samuel Beckett's modernist sensibility than the biopic. The Irish writer who moved to Paris, found inspiration in the French language and became one of the most innovative literary artists of the second half of the 20th century was allergic to the uplifting pieties and sentimental depths that are the mainstay of cinematic biographies.

Publicity and self-promotion were anathema to this highly private author, who died in 1989. It's safe to say that he would not have liked to be the subject of a film. When Beckett learned that he had received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969, he holed up in a hotel in Tunisia for fear of the celebrity circus. Before long, he let Swedish officials know that he was honored by the award but would not be able to attend the ceremony.

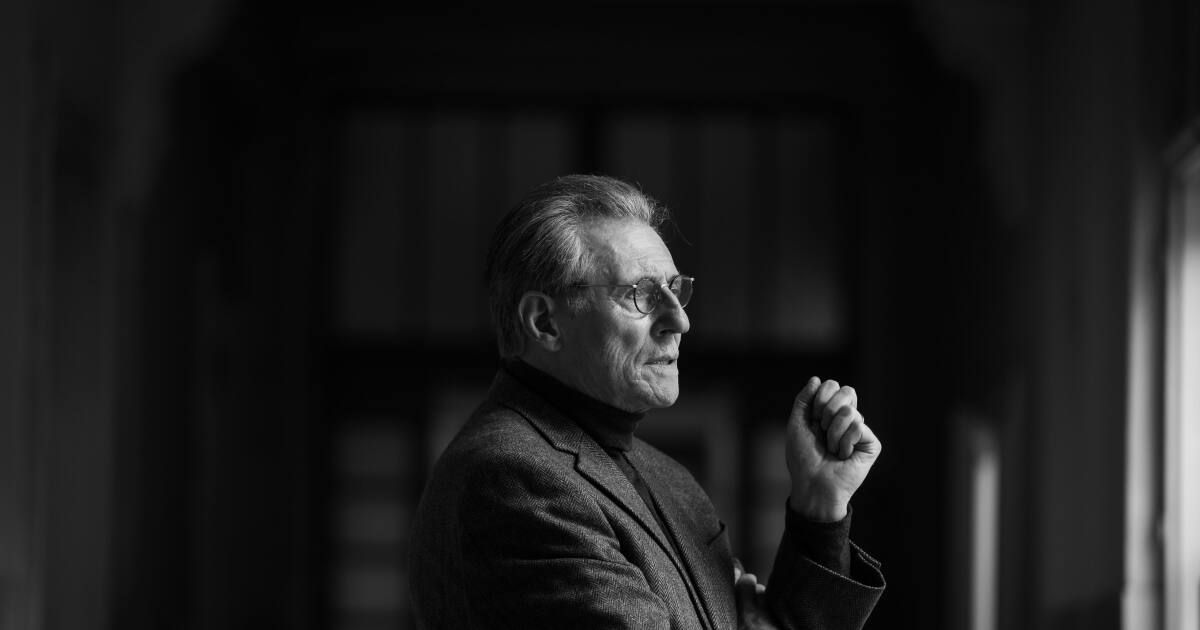

James Marsh's film about Beckett's life, Dance First, shot in crisp black and white by cinematographer Antonio Paladino, doesn't let this detail get in the way of a conventional opening. The film opens with Beckett (Gabriel Byrne), dressed for a funeral, at the Nobel Prize ceremony in Stockholm.What a catastrophe!” he murmurs to his wife, Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil (Sandrine Bonnaire), as his literary praises are sung from the podium.

Credible biographical sources attribute the commentary on the catastrophe to Beckett's wife, who was also reluctant to be the centre of attention. But screenwriter Neil Forsyth's plot swings boldly between faux-realism and blatant surrealism.

In a breach of verisimilitude, not to mention decorum, Beckett bursts onto the stage, grabs the check and begins clambering noisily up the side wall to escape public scrutiny. He heads to an archaic location that could be the setting for a Greek tragedy or even one of his own plays, where he engages in a purgatorial dialogue with his alter ego.

Fionn O'Shea in the film “Dance First”.

(Photos of magnolias)

Byrne, acting opposite him, brings these aspects of Beckett's conscience to dialectical life. Sombre and repentant, his evening-dressed Beckett explains that he has accepted the prize so that he can give away the money. But his tweed-clad, serenely sceptical Beckett asks with double meaning: “Whose forgiveness do you need most?”

The film is divided into retrospective chapters about those loved ones who weigh heavily on Beckett's conscience. This device, which has the clumsy air of a middle-class play, provides a convenient, if theatrical, way of breaking up his biography into manageable chunks.

The film’s title evokes a line from Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” that gives dance a natural precedence over thought. But “Dance First” has little in common with Beckett’s absurdist aesthetic.

With his ruthless dedication to minimalism, Beckett reinvented whatever art form he was working in. In plays like “Waiting for Godot” and “Endgame,” novels like the Beckett trilogy (“Molloy,” “Malone Dies” and “The Unnamable”) and even “Film,” his 1965 foray into screenwriting, he strips the work of all the superfluous, scorning conventional expectations and discovering what can be communicated when all the scenery has been swept away.

Meaning is not imported into Beckett’s work, but expressed through a seamless alignment of style and content. Instead, Forsyth’s script for “Dance First” serves as a container for reportage and biographical interpretation. The film has a journalistic quality, offering an easily digestible summary of Beckett’s life, with all the important moments clearly enumerated.

What redeems the film is the human attempt to reach beyond the myth to the man. Byrne's Beckett may be less austere, outwardly and inwardly, than the prevailing image of the author. Exuding a weary melancholy, the actor betrays an incongruous longing for the confessional, resolutely portraying the elderly Beckett stoically dragging his corpse to the finish line. With physical suffering an inexhaustible source of black comedy and a recurring metaphor for the human condition in Beckett's writing, the depiction of mortal decay is apt.

But an air of invention hangs over the film, even if it sticks to a factual framework. By condensing Beckett’s journey into a series of snappy, self-contained chapters, “Dance First” can’t help but distort and over-dramatize.

Beckett is known to have had a strained relationship with his demanding and disapproving Protestant mother, May (Lisa Dwyer Hogg), the first stop on the acclaimed author's guilt trip. The young Beckett (played with intriguing aplomb by Fionn O'Shea) fled Ireland in part to escape her iron grip, but the film doesn't suggest other dimensions of a bond that would haunt Beckett's work throughout his career.

The section on Lucia Joyce (a feral Gráinne Good), James Joyce's mentally ill daughter who convinced herself that Beckett would marry her, and the scenes recounting Beckett's involvement in the Resistance during World War II are condensed in ways that seem spurious, but the actors have moments that transcend the summative treatment.

The interactions between Beckett (O'Shea) and James Joyce (Aidan Gillen), an initial mentor who resists the role but is eventually won over by the younger man's reverence and rigor, are handled with welcome complexity. Joyce (Gillen) recognizes in Beckett not only a prodigy but also a potential husband for his unstable daughter, a plan that galvanizes his no-nonsense wife, Nora (Bronagh Gallagher), who is far less subtle in her manipulations.

Beckett's detachment, his ability to resist becoming a prisoner to the needs of others, allows him to become the Great Writer, but at a cost that becomes more apparent as the film focuses on Suzanne (played by Bonnaire as the mature wife and Léonie Lojkine as the girlfriend who becomes indispensable, romantically and practically, to him). Bonnaire and Lojkine preserve not only the character's dignity but also her far-sighted intelligence and tactical discretion.

Suzanne understands the mission of being Beckett's wife and being alert to anything that might distract him from his higher mission. It is unclear whether Beckett would have realized his gifts without the stability she provided. He was loyal, in his own way, to the woman who stood by him as he recovered from a near-fatal stabbing in a random incident of street violence in 1938. She stood by him lovingly and bravely during his dangerous war years working with the Resistance.

When Barbara Bray (Maxine Peake), the BBC script editor who becomes Beckett's long-term lover, enters the story, Suzanne carefully navigates the dangerous marital waters. The pain Beckett inflicts on both women is silently reflected in her beautiful, haggard face. She may be selfish, but it would be a mistake to think she is heartless.

Language is inadequate to the suffering it has caused, but Beckett manages to give it artistic form in “Play,” his daring one-act play in which a husband, wife and lover retell their story of infidelity at lightning speed while entombed in funerary urns in an indeterminate afterlife.

Beckett may have a reputation for being gloomy, but he was also a sportsman who loved rugby, cricket, tennis, attractive women, male friendship and good whisky. O'Shea has room to include this other Beckett, but Byrne's reclusive version of the character looks like he might be more at home in a monastery or an academic library.

Yet there is the emotional acuity of a writer who felt things too deeply to stoop to cheap sentimentality. “Dance First” may not be particularly Beckettian, but it personifies a figure who, destined for the pantheon, never doubted that she was human, all too human.

'Dance first'

No rating

Duration: 1 hour, 40 minutes

Playing: Opens Friday, August 9 at the Laemmle Monica Film Center, West Angeles; Laemmle Town Center, Encino