Cillian Murphy had just spent the day filming what seemed like 30 scenes of “Oppenheimer” with the desert sand kicking up and exploding in his eyes when his co-star Robert Downey Jr. greeted him, trying to lift his spirits. And (that’s how Downey remembers it, and when the legend becomes true, print the legend), Murphy lamented how, when he had returned to his “$18-a-night hotel room” the night before, he found his suitcases in the hallway and thought: “Shit! I haven’t left yet. I have to sleep!”

“Every indignity that could happen to someone trying to do something… It was like Job’s tears,” Downey recounted after a recent screening of Christopher Nolan’s blockbuster. “Forget about the call sheet and the work. It was everything else. “It was the most Irish experience I have ever witnessed.”

Nearly two years later, Murphy and I are talking on a late fall day in Los Angeles. He’s taking off his coat and moving his chair closer to the sun because, yes, he’s Irish, and part of the Irish experience is to get as much sun as possible. possible when the opportunity presents itself. As for what Downey attributes to his homeland, Murphy can’t help but laugh.

“I don’t know if that means the Irish are more predisposed to suffer,” Murphy says, smiling. “I think he’s being very sweet and saying that we were like a group, moving at a great pace. We just stayed in motels along the highway and moved around. It wasn’t glamorous. The way Chris works is to keep everything equal. Nobody has trailers or personal makeup. They all get on a bus. It feels like an independent cinema, but on a large scale. And that’s how I enjoy working.”

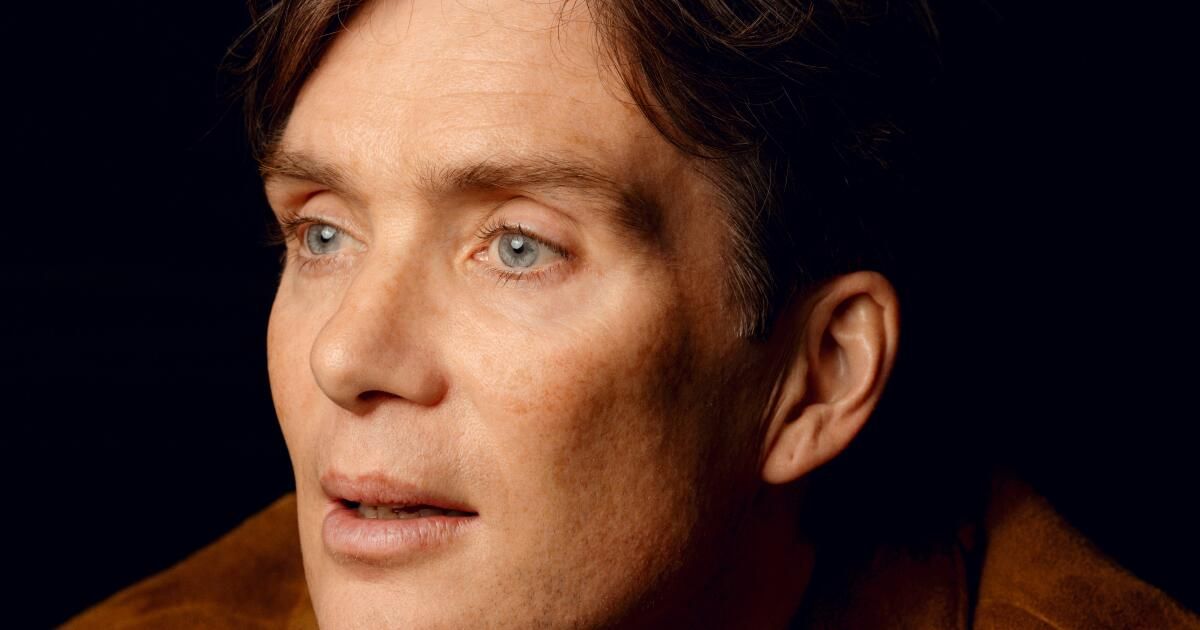

Cillian Murphy and Christopher Nolan have made six films together.

(Melinda Sue Gordon/Universal Pictures)

Murphy, 47, also enjoys not working, and has had a successful enough career in the two decades since his film breakthrough in Danny Boyle’s 2002 zombie classic “28 Days Later” that he can describe those periods as “happily unemployed.” That’s where he was a couple of years ago. He had finished filming the sixth (and final) season of the entertaining BBC crime drama “Peaky Blinders” and was in the midst of six glorious months enjoying the company of his wife, Irish visual artist Yvonne McGuinness, and their two children. teenagers. . Then Nolan called out of the blue.

Actually, it wasn’t Nolan, but his wife and producing partner, Emma Thomas. It couldn’t be Nolan, because Nolan doesn’t have a phone, an eccentricity that is either endearing or infuriating depending on the context. Thomas handed the phone to her husband, who told Murphy (in what the actor calls an “incredibly understated British style”): “I’m making a movie about Oppenheimer.” Pause. “I’d like you to play Oppenheimer.”

And just like that, Murphy was no longer happily unemployed. He played the title character in Nolan’s sprawling drama about the physicist known as the “father of the atomic bomb.”

“A big moment,” calls it Murphy, who is no stranger to self-restraint. He pauses. “A big problem”.

In conversation, Murphy is pleasant and thoughtful when talking about his home country (he could and ought write a book about the Ring of Kerry or at least narrate a self-guided tour) and the arts. He had read that Nolan sent him photos of David Bowie wearing voluminous, high-waisted pants from the singer’s Thin White Duke era as a visual reference for the gaunt silhouette he envisioned for Oppenheimer, a man who possessed a work ethic so manic that he forgot about eat and subsisted on martinis and Chesterfield cigarettes. I pull out a photo of Bowie taken shortly before his death, dressed in a smart suit, black fedora, and beaming.

“It seems a little strange, which is what we were going for with Oppenheimer, I think,” Murphy says. He holds my phone and looks at Bowie. “One of the greats. that last album [“Blackstar”] It was fucking extraordinary. What a gift to leave us. “No one else could have turned out like that.”

Reflecting on Christopher Nolan’s offer to star in “Oppenheimer,” Cillian Murphy remembers it as “a great moment.” Pause. “A big problem”.

(Ryan Pfluger / For The Times)

Murphy’s most striking feature, his piercing blue eyes, has been widely reviewed, and for good reason. “Oppenheimer” co-star Matt Damon points out how he got distracted working with Murphy. “It’s a real problem when you work on scene with Cillian. [because] Sometimes you find yourself swimming in their eyes,” he told People.

Those eyes were the first thing that drew Nolan to him. The filmmaker was flipping through a newspaper while he was writing “Batman Begins” and came across a photo of Murphy from “28 Days Later.” He couldn’t shake the image of this actor with the shaved head and “crazy eyes” and he made a point of reuniting with Murphy for Batman, a role he eventually went to Christian Bale.

They’ve made six films together so far, with Murphy playing the menacing Scarecrow in the “Dark Knight” trilogy, a petulant corporate heir in “Inception” and a character known simply – and quite accurately – as “Shaking Soldier” in “Dunkirk.” . “They share a mutual interest in conveying a character’s emotional conflict through close-ups that linger on the actor’s face and allow the audience to feel an inner turmoil. In Oppenheimer’s case, it was the searing anguish of a man a little late to realize and appreciate the consequences of what he had created.

“For me, great screen acting is about ‘showing, not telling,'” says Murphy, “and being able to convey emotion and energy simply by strength, presence or charisma.”

I ask him about influences there, but Murphy demurs, saying that if he starts listing actors, he’ll wake up in the middle of the night and think, “Holy shit, I left that person out.” He reiterates that his favorite cinematic moments are not great scenes but seeing the actors reflecting, inactive, doing nothing, but revealing everything. “I found that convincing in the highest order,” he says.

Murphy had ample opportunity to do just that in “Oppenheimer,” playing a character caught in a moral dilemma of his own making.

“I knew it would have to be a small, quiet performance, because the themes are so fucking huge,” Murphy says. “What’s going on inside her heart and mind can’t be described in a big way, particularly when it’s captured on an Imax camera and will be shown on a fucking 80-foot screen. “I knew most of it would have to be delicate and small.”

Murphy doesn’t like to dwell on what he once called the “monastic experience” of the film’s 57 days of shooting or the months it took to decompress afterwards. Such a conversation would be too close to the “Irish experience” that Downey had mentioned. But all of these efforts made me think of something Emily Blunt, who plays Oppenheimer’s wife Kitty in the film and worked with Murphy on “A Quiet Place Part II,” noticed about him.

“She said that off set, you’re a hoot,” I say, searching for an example or two. Murphy declines, but expresses how her friendship with Blunt created a trust that influenced their portrayal of lifelong companions.

“He’s also one of the funniest people and I have a rule that I can’t work unless there’s some levity on set,” says Murphy. “There has to be some levity. A lot of the films I make are quite heavy and go to dark and challenging places, and you have to be relaxed to do that. So I don’t walk around in a state of fucking anguish. I need to feel comfortable. I can’t be in that dark place all the time. “I don’t have the stamina for it.”

“For me, great performance on screen is about ‘showing, not telling,'” says Cillian Murphy, “and being able to convey emotion and energy simply by strength, presence or charisma.”

(Ryan Pfluger / For The Times)

Murphy saw “Oppenheimer” at the film’s world premiere in July in Paris. Two days later, he and the rest of the cast left the London premiere to show their support for the impending SAG-AFTRA strike. When he returned to his home in Dublin, his wife and children had already seen “Barbie,” so Murphy went alone to the theater to complete the “Barbenheimer” experience.

How do you go incognito to the multiplex? I ask.

“Now it feels really good to go to the movies,” says Murphy. “With commercials and trailers, I’m always half an hour late, I get in and then I get out.”

I complain that that half hour seems to get longer every year. Murphy agrees. And yet …

“The greatest form of democratic collective art is sitting in a dark space with strangers,” he says. “To be part of a movie that people went to see several times and part of a great moment for cinema, that frenzy for those two movies, was just lovely. I don’t know if we’ll ever see it again, but I’d like to hope so.”