Twenty-five years after “Almost Famous” brought his origin story to movie screens, Cameron Crowe is thinking back to his roots as a teenage music journalist.

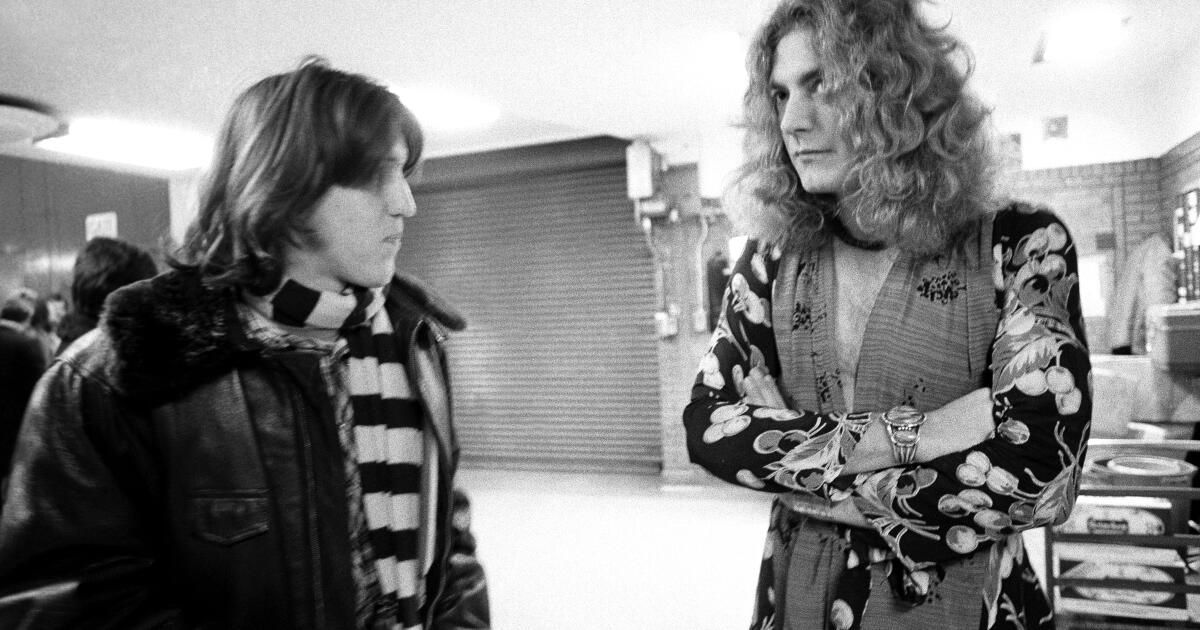

The Oscar-winning filmmaker's new memoir, “The Uncool,” is a tender and revealing account of his adventures covering artists like the Eagles, Led Zeppelin and Joni Mitchell for Rolling Stone in the 1970s. Back then, a relative dearth of serious rock writing meant that bands opened the doors to their private planes and let him tag along. with a notebook and a tape recorder for weeks at a time.

The book, out Oct. 28, explores Crowe's relationships with David Bowie, whom he followed around Los Angeles as Bowie built his Thin White Duke persona, and with Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner, whom he describes as a kind of mentor-antagonist. But he also reflects on what Crowe, now 68, calls the “strange chemistry” of his loving but complicated family, including the way his parents handled the suicide of his older sister Cathy at age 19. (He will speak about the book on November 20 and 21 at the Montalbán Theater).

Crowe, whose films include “Say Anything” and “Jerry Maguire,” is working on a Mitchell biopic that is rumored to star Meryl Streep and Anya Taylor-Joy; Next year he plans to publish a volume of his journalistic compilation. Over coffee and bagels on a recent morning in Culver City, he talked about “The Uncool,” a missed opportunity with Bob Dylan and Wenner's much-discussed expulsion from the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

I think it's fair to say that back then you were known for being quite understanding of your subjects. Who did you come across?

When I started, there were some editors at Rolling Stone who really felt like they needed to tell me that you can't just write about people you admire. I accepted two tasks and thought: Okay, I'm going to try what later became known as snark.

I thought Bachman-Turner Overdrive were a little silly, but they were having big hits and Rolling Stone wanted the story, so I went on tour for three days. Opening act for them: Bob Seger, who was between professional successes. I remember sad Bob Seger on a pay phone in a hallway talking to someone, like, “I'm headed to Michigan, where I should be a god, but I'm opening for Bachman-Turner Overdrive.”

I once saw Bob Seger in a dressing room eating a chocolate chip cookie on a Styrofoam plate.

It's like a portrait of Edward Hopper.

Sorry, continue with BTO.

They were full of themselves: three big hits and they think they're the Beatles. So I just quoted them being completely pompous. Then I felt like s—.

Because they asked you to do something that wasn't yours and you forced it?

Yes. I remember watching William Buckley on TV when I was little and saying: Bite. And if Yo bit? But here was the interesting thing: they loved the story. “This sounds like us, man!” But I felt stained by it.

Another thing that still puts me off a little: I wrote about John Travolta. [for Playgirl in 1977]. I was in a particular place, not unlike Bachman-Turner Overdrive, where I was just getting a taste of stardom, and I made a comment like, “Yeah, good luck.” I had a journalist friend who was a good friend of mine, and he called him up and said, “Why did Cameron do that? I really enjoyed talking to him, and he was looking for where he could shoot an arrow at me.”

Years go by and I end up at the same table with him when “Jerry Maguire” came out. Kelly Preston, his wife, had been in the movie and he had advocated for her to do it and all that. There was a moment where I said, “I really regret what I wrote about you because it wasn't me and I don't think it was you either.” Damn Travolta looked at me and said, “I appreciate what you're saying, but there's no way I can trust you again.” I can still see his face. And it wasn't “I'm so hurt,” you know? It was “You weren't honest with yourself, were you?”

What writing are you especially proud of in the book? You have a scene where you're in Chicago with Led Zeppelin and you meet a woman in a bar. You say, “She was a single mother and a school teacher on her day off. She invited me to her apartment and I watched her pay the babysitter.”

I'm proud of that. What that did (and you can't really do with screenwriting in the same way) just captured a feeling. I found it real, honest and a little sad. I'm also proud of what I write about Ronnie Van Zant. [of Lynyrd Skynyrd]. That guy was interrupted and had a big career ahead of him. More people need to put a crown on their heads.

You do a good job in the book of speeding up and slowing down as you go through your memories. It has some tempo changes.

I hope you like music.

Cameron Crowe at the Sundance Film Festival in 2019.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

One of the longest sections revisits a meeting with Gregg Allman. He spoke candidly to you about his music and the death of his brother Duane. Then he turned on you, accused you of being a cop and took the tapes of your interviews.

The Allman thing was in my gut for decades, so he just wrote the way he did. It was very emotionally violent, and more violent than I think Gregg… well, no, I think Gregg knew. But it was a tour bus anecdote in his autobiography. I felt: Come on, man, that's not real.

When I made the audiobook the other day, I started crying. It really scared me to death. I didn't have a family where I heard domestic things happening in the next room. So, being 16, being on your big trip and having someone hit you with hard fists, it was still there.

In a way, that scene feels like…

But I never hated him for that.

No, I didn't have that impression when writing.

I felt like I had somehow discovered a wound. I wasn't a doctor, but there was the injury and I thought, “I'm sorry you're so upset about that.”

The scene seems to me to be the heart of the book.

I looked at the boy: he was not much older than me and there was a lot going on inside him, a lot of pain. And I also had that kind of pain because I had also lost a brother.

Who is one artist you got wrong?

I did an interview with Bob Dylan for Los Angeles magazine and I was so wrong that they didn't publish it. It was around the time of “Street-Legal” and we did it where they were recording. He had a room in the rehearsal space and the top 10 albums of the moment were spread out on this bed, like he had asked someone to bring him the top 10 albums. I think Seger was one of them. The interview really didn't go well. It was like there were no good answers. Or maybe my questions weren't big enough. He had done “Renaldo & Clara” and talked about Shelley Winters being a very important artist. I say, “Shelley Winters? That person on the Johnny Carson show?”

Years later, I got the job of making notes for [Dylan’s box set] “Biography”. He came to my house for two hours and sat at this little red table in our living room. I think because it was for him, he had something to say. In the interview I basically said, “'Forever Young,' go ahead.” And he answered the questions! “Well, I wrote it in Arizona and I was thinking about…” I was like, “Who is this?” this boy?”

Who let you down?

I was given the task of doing a cover story on Steve Miller. It wasn't like I was burning with the desire to write about Steve Miller, but I liked the records; The first things were great. So I went to San Francisco, to the top of this hotel. It was very cold and all the windows were open. Everyone was shivering except Steve Miller, who was wearing a big coat. I started talking to him a little bit and he said, “What makes you think you know enough to interview me? I think you're too young to understand my full musical scope.” Everyone in the room looks at me, like, “How do you feel about what Steve just told you?” The ping-pong ball clicks in front of me. Am I going to hit him back? I thought, “Well, I guess so, and…” But I went and wrote a memo to Jann explaining why I didn't want to do the story, which he gave to Steve Miller.

Have you spoken to Miller since then?

No, but I think he still remembers it. He said something at the Rock Hall about it.

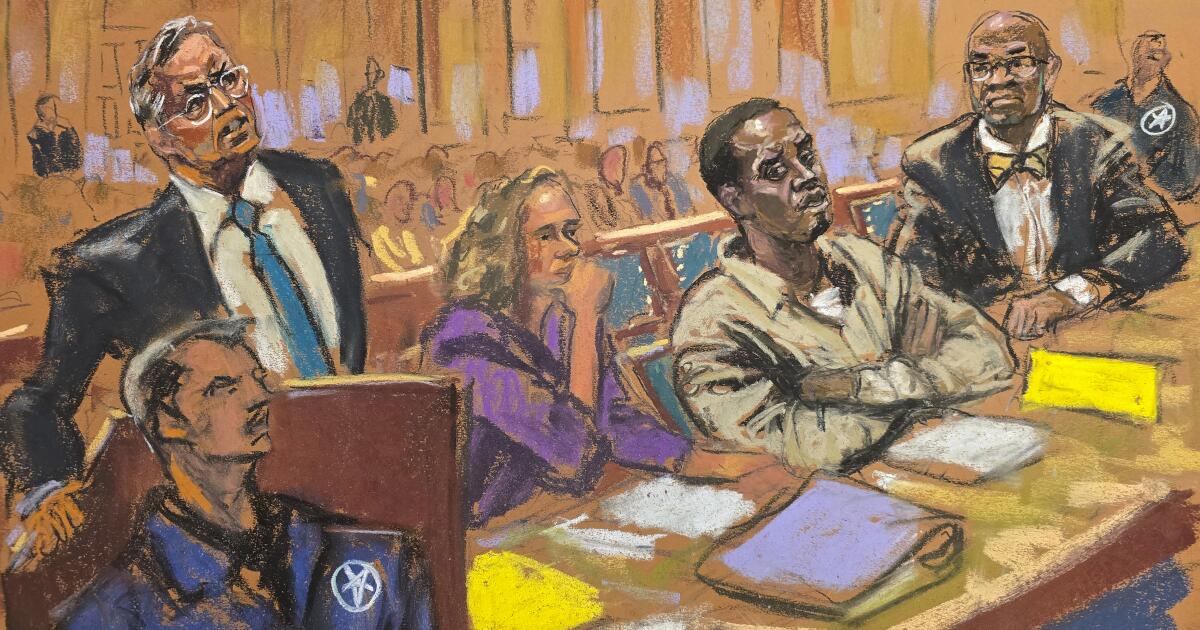

In 2023, Wenner was ousted from the Rock Hall board of directors after an interview with David Marchese of the New York Times about his book “The Masters.” Marchese asked why Wenner interviewed only white men in the book, and Wenner suggested that black women and artists, including Joni Mitchell and Marvin Gaye, were not articulate enough. Did you interpret those comments as a betrayal of Wenner's true self, or was it the real Jann that came to light?

I think it was the real Jann that day. The boy you imagine he was [by] Reading those comments, I didn't recognize that guy as Jann. I recognize that guy probably wrote that book and felt very good about the people he interviewed and explained why he chose the people he called teachers. But it's a “Have you stopped hitting your wife?” question, you know? I don't know if Marchese was trying to play gotcha, but I think that's how Jann answered the question that day.

To me, Jann is a guy who encouraged a lot of people to come together and write about music at a time when no one had a place to do so. Being young, walking into that office and seeing these vibrant people who were five or six years older than you but rowing together to tell these stories, it was super exciting. And Jann created that atmosphere. Later, as a director, I realized how important it is to be the person who brings everyone together. And it's not easy.

Cameron Crowe and Joni Mitchell in San Diego in 2019.

(Bruce Glikas/WireImage)

Would you say that the opprobrium that fell upon him was justified or excessive?

Probably excessive if you couldn't learn more about the story. If you could see Jann from a different perspective, you might better understand what he was trying to say. But this is what happens in clickbait culture: you get the four phrases that make people crazy or super happy, but mostly outraged. I would probably say it differently today.

I'm sure he would. But is it because he feels different or because he was stung and now he would be careful?

I think he was wrong about Joni and he knows he was wrong about Joni. She is the most eloquent of all.

What is the type of music that makes you feel old now?

I have two sons who like melodic death metal. That was never my thing, but I went to a Sleep Token concert with them and was blown away by how emotional it was.

I love that I asked you about music you don't understand and you told me something you totally understand.

I mean, Sleep Token; In a way, it is singer-songwriter music.

You are known for your excellent needle drops. Who uses music in their movies even better than you?

Quentin [Tarantino] it often does. To use Jim Croce like he did [in “Django Unchained”]or using the Delfonics on “Jackie Brown”: that was a crusher. I watched this series “Wayward” with Toni Collette and it hurt me to watch it. Michael Angarano, who appears in “Almost Famous,” plays the little one: “11!” – made a really nice movie called “Sacramento,” and in the middle of it is this dark Ron Wood song that is fantastic. I'm like, fuck it, I've got to make another movie and show some muscles.