Give “Oppenheimer” production designer Ruth De Jong the choice between the control that comes with a studio and the vagaries of outdoor filming, and she will always build outdoors.

“For me, the fascination of getting into production design is having nature as a backdrop,” says de Jong, whose heavy credits before working for Christopher Nolan include the episodic western “Yellowstone” and Jordan's “Nope.” Peele. He even lives in Big Sky Country, zooming in from his home in Montana (where he moved after working on “Yellowstone”). “I like to be able to have an extension, the elements, the climate, the landscape. Placing your sets under a rotating sun, so your set changes light all day, compared to a sound stage, where everything is rigged. It is absolutely my preference to go to the middle of nowhere. And it is more difficult.”

When it came time to erect the movie version of J. Robert Oppenheimer's Los Alamos (the remote southwestern outpost that housed the Manhattan Project), de Jong had neither an Army Corps of Engineers nor $2 billion at his disposal. disposition, as the legendary physicist did have. So she and her dedicated team absorbed historical maps, plans and images and created a quarter-scale version with key buildings around a central T-shaped intersection.

Ruth De Jong consults with cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema and writer, director and producer Christopher Nolan on the set of 'Oppenheimer'.

(Melinda Sue Gordon/Universal Pictures)

What De Jong achieved also suggests a striking difference from Oppenheimer's construction project: in the 1940s there was already a city from which to expand. De Jong built his from scratch on an explored arid mesa in New Mexico that offered epic 360-degree views. “There was no infrastructure,” he said. “We had to open a road to get there on all-terrain vehicles. “It literally came out of this plateau, which you see in the movie.”

And yet, with only eight weeks to build the film's Los Alamos, De Jong had to put aside his natural obsession, the kind that says that if a street runs in a certain direction and a building is in a specific place, the set should reflect that too. “Chris told me, 'You have to divorce yourself from research. We are making an essence of Los Alamos. We're telling a story, I'm not making a documentary.'”

“Oppenheimer” production designer Ruth De Jong enjoyed working with the open expanse of New Mexico.

(Universal Photos)

Is it, then, the illusion of the documentary, perhaps? De Jong always seeks to base a script, so that the viewer feels transported by the reality of the stage, not worried about it. As she says: “How does the viewer get lost so as not to be distracted by the sets? It's something I find difficult to address every time. How do sets disappear to where people say, 'Oh, they didn't have to build anything.' That was there.'”

His education in the artistic authenticity of a film set could not have been more excellent, considering that his mentor and close friend is the legendary production designer Jack Fisk. “Like Jack, I came from a fine arts background and studied photography and light, sculpture and painting,” says De Jong, whose first big job was with Fisk on “There Will Be Blood.” “I was under Jack for seven years as an art director, and he had a specific way of working that resonated with me as an artist. “I think of production design essentially as a giant painting in the real world.”

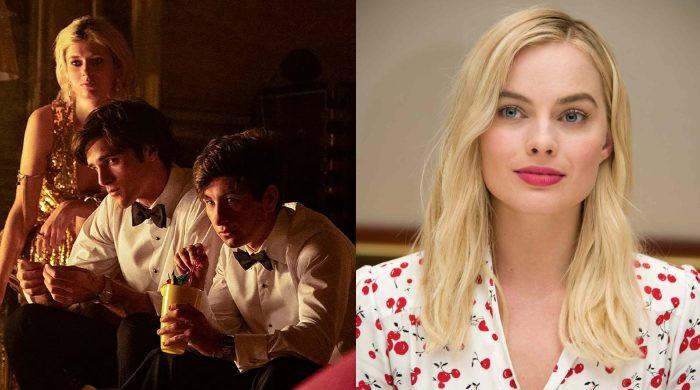

(All of “Oppenheimer’s” buildings, here with Benny Safdie and Cillian Murphy, were built from scratch.)

The list of great directors De Jong has worked with is impressive, from Terence Malick to David Lynch, but she says Nolan stands out in one essential way. “I've never really met a director who knows what each department does and needs. He was very into this with us,” she says, especially when it comes to thinking about a budget. “Chris knew ways to support us. He would say to me, 'Ruth, have you considered the sheds at Home Depot? Could that get us there? We laughed and Chris said, 'No, I'm serious.' And we used the Home Depot sheds because we could reach our number!

At the same time that de Jong thinks about large-scale components, he is aware that even office sets feel “appropriate and purposeful, not just putting things on a set to say it's 1945.” Authenticity meets character work, so to speak, so when lead actor Cillian Murphy opens a drawer or looks around Oppenheimer's Los Alamos office, he'll find not just something period-appropriate, but objects related to who you are interpreting.

“I think it is very important to design so that it is precise, but also natural for the spaces. I think everyone appreciated the commute to Los Alamos, because there was no cell service. Nobody had it. So your head is in it, your mind is in it, you're coming to town the same way Oppenheimer would have every day. He places them right there.”

De Jong understands that much production design work is now done using modeling programs to fill green screens or sound stages, but those jobs don't satisfy his location-driven ethos. “The tangibility of having to be physically present to build, I don't ever want that to go away,” he says. “When they say, 'Keep the kids off the screens,' I say, 'Let's keep the adults away from them!' Go out into the world and create this!