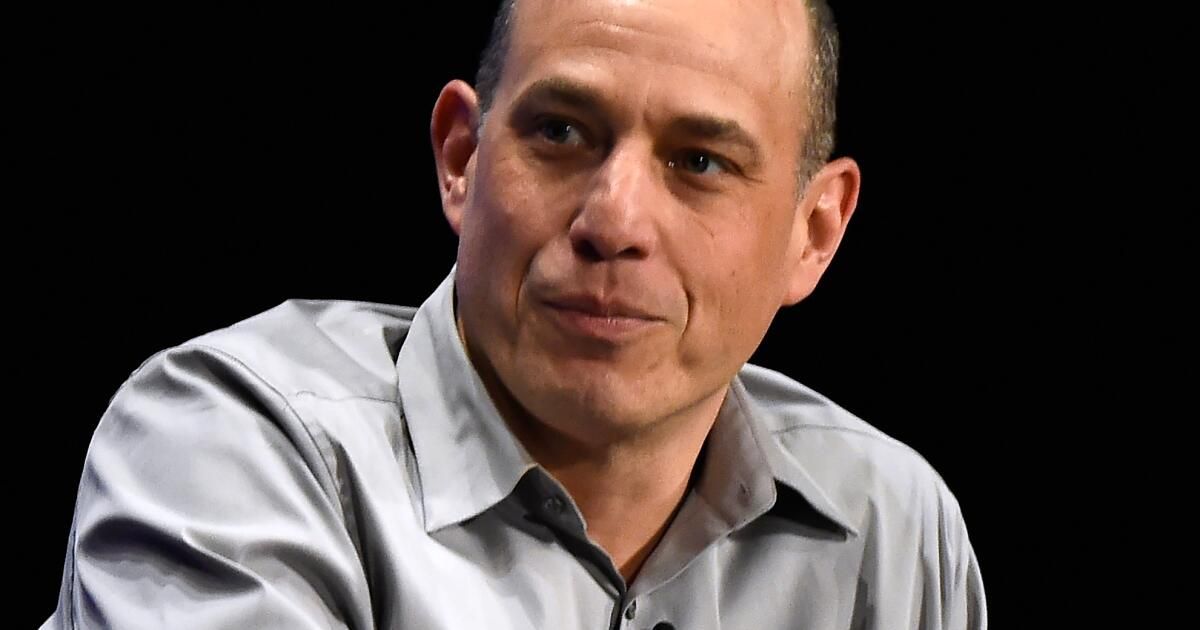

Bruce Eric Kaplan started a magazine in the midst of the pandemic, hoping to make sense of a world shaken by the vapor trails of Donald Trump's presidency and COVID-19. The external chaos was seeping into his personal life, manifesting itself in a series of indignities that did little to calm his anxiety about a country turned upside down. The veteran New Yorker cartoonist and television writer-producer was also immersed in another kind of madness: trying to put together his own passion project, a small-screen show about a May-December romance.

“I'm looking to have a deep experience,” the veteran of “Girls,” “Six Feet Under” and “Seinfeld,” among other shows, writes in his first diary entry.

Spoiler alert: it doesn't happen.

But Kaplan has turned the diary begun in early 2022 into a book. “They Went Another Way” is a funny, melancholic and moving diary of Kaplan's personal year of plague.

“I basically started this journal so I wouldn't go crazy,” he says over coffee and bagels at the Clark Street Diner in Hollywood. “After finishing the book, I read 'Big Magic' by Elizabeth Gilbert, which basically tells the reader to listen to the world and write down everything it tells you. That was my process.”

Kaplan didn't like what the world was telling him: although he was committed to writing for television, he was trying to fend off growing cynicism about his ability to create meaningful work in Hollywood. At the time, the TV veteran had been unemployed for more than six months and his children's private school fees loomed over him like the sword of Damocles.

But existential desperation doesn't pay the bills, so he presses ahead with his project. Kaplan's first diary entries are hopeful: his agents send their pilot to Glenn Close, whose representatives tell them that he has read it and wants to do it. Kaplan finds a ray of optimism in an uncertain time: an A-list actor who wants to make his show.

But Hollywood is a place where hope often dies, and “They Went Another Way” is a comic manual on how good ideas are slowly strangled by an unwieldy and inefficient mainstreamocracy whose lingua franca is the cleverly evasive lie.

“They Went Another Way: A Hollywood Memoir” by Bruce Eric Kaplan

(Henry Holt and company)

Things start promisingly, like all first acts. Nearby, Kaplan and “Palm Springs” director Max Barbakow meet on a Zoom call; She gushes about Kaplan's script, they discuss possible co-stars and possible production locations. Kaplan agents create a list of ideal buyer introductions. As this project slowly comes together, two prominent showrunners are mentioning Kaplan's name as a supervising producer on their new show. It's all happening, but Kaplan is battling writer's block and a broken heating unit, among other disruptions both national and global.

Thus begins Kaplan's mad fight to regain his sanity, as the television writer attempts to plug the leaky vessel that is his life, which he recounts in embarrassing detail in his book. “I was at a crossroads at that point,” Kaplan says now. “My wife and I were also trying to decide if we wanted to move to New York with our kids in the middle of all this. I just felt, 'This is what I'm supposed to write about, the things that are really happening to me.'”

It doesn't take long for the initial burst of heat to cool down in Kaplan's project. Soon, he finds himself in a position all too familiar for anyone trying to make it in Hollywood. “I'm waiting to hear if Max Barbakow is officially attached to Glenn Close's script,” Kaplan writes. “I'm waiting to find out when I'll meet with Will Forte to talk about my show in New Zealand. And in fact I'm waiting for other things that I don't feel like writing about.”

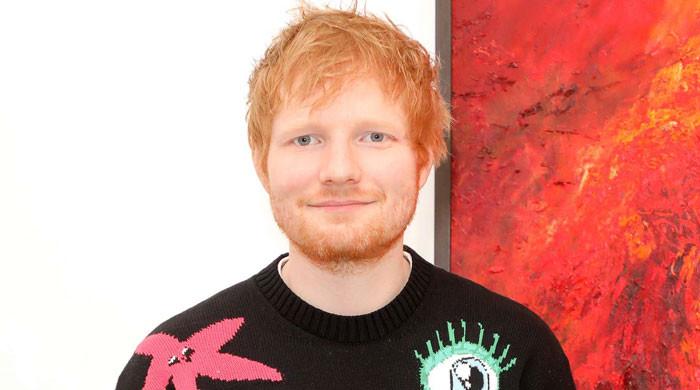

Kaplan is drawn into a vortex of elongated time, where a day becomes a week, becomes a month, and where deadlines are written in the water. Close emails Kaplan about contacting Pete Davidson as her co-star; According to Kaplan, he has “great chemistry with” the “Saturday Night Live” alum, a friend of his. Close sends a copy of the script to Davidson, who reads the first 11 pages and wants to do it, which, Kaplan writes, “is quite something, since her character doesn't even appear until the later pages.”

The process of getting everyone on the same Zoom call becomes unnecessarily complex and Kafkaesque. Davidson repeatedly calls in sick, when in reality simple Google searches reveal that he's out of the country with his girlfriend Kim Kardashian, or something like that. Then, when it looks like momentum might be turning in Kaplan's direction, there's a demand for more: more story, more plot, more gratuitous writing. Hope always crashes against the banks of disappointment. Showtime wants to make Kaplan's show, but Netflix seems to be in “first position.” Then they both leave.

This push and pull, of taking one step forward and then another step back, leaves Kaplan spiritually exhausted. He keeps his anxiety down by meditating, exercising, and obsessively cleaning his house. He nearly loses his mind trying to complete his daughter's private school application, and he and his wife are injured by stray soccer balls at separate events at his daughter's team's practice. Consider alternative careers. “My escape plan is… to bring turkey sandwiches to New Zealand,” Kaplan writes. “I'll have some turkeys shipped there and I'll have a turkey farm…if this script doesn't sell, I'm definitely going to explore becoming a turkey farmer in New Zealand.”

Nothing is certain, but the streaming cosmos has given that truism a boost of power; There are so many potential projects spread across so many creators that it seems as if no one could commit to anything, much less focus on one thing, for a long time, which has been made even worse by Hollywood studios severely scaling back on greenlighting . any new project. Risk aversion has become an end in itself. Kaplan, who began his career in the four-network era, has seen the changes firsthand.

“When there were four networks, my agent would set up pitches and you would have a meeting within 48 hours of that initial call,” Kaplan says. “In one day you would know if they wanted it or not. The executives asked about the idea and the characters. That was it. They didn't ask what the ending of the first season was going to be or ask you to design the second season.”

When Kaplan, against his better instincts, agrees to write a second script for a potential buyer, things don't go well. Close flatly rejects the script, telling Kaplan, “If I don't find it interesting, I guess everyone will find it uninteresting.” This leads Kaplan to wonder in his journal whether “thinking that everyone would have the same feeling as you was a trait of severe narcissism.”

Suffice it to say that everything eventually dissolves into the ether: Close disappears, as do all of Kaplan's other projects. The end of the year finds Kaplan in the same place he was in January, but not without having endured a flurry of Zoom calls, emails and texts that leave him exhausted. Still, he struggles to start over. It's all he knows how to do.

“This is my reality.” he says, “and I'm just trying to make the most of it.”