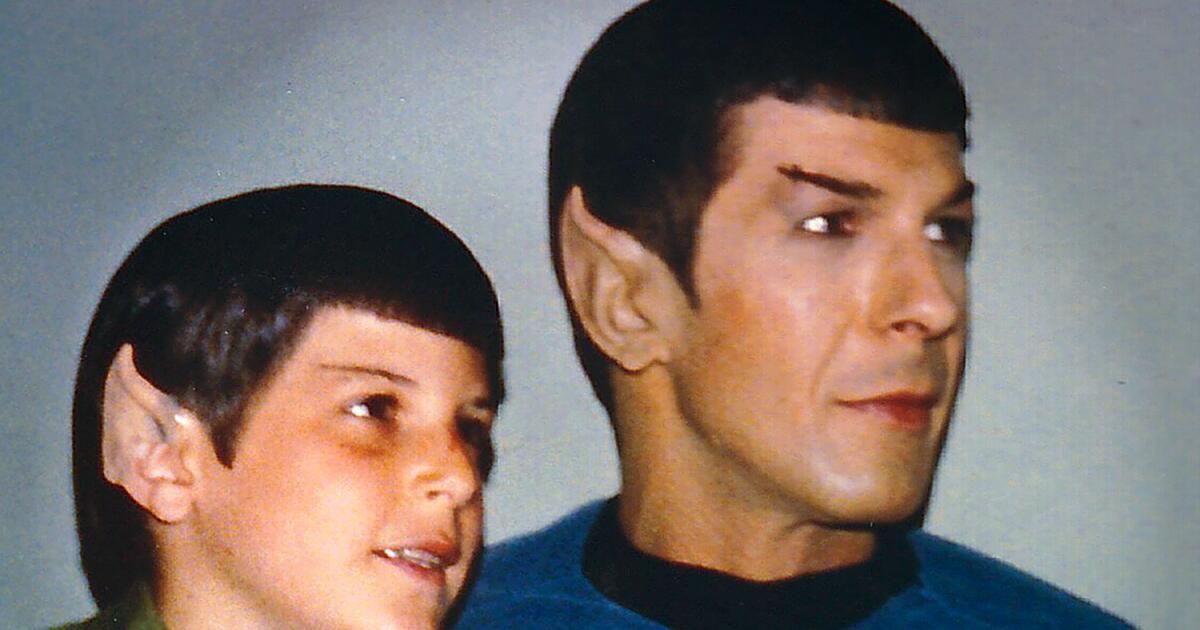

Even after his pointy ears were removed, Leonard Nimoy had trouble expressing his emotions. Nimoy, a highly repressed, high-functioning alcoholic, connected with the character of Spock on “Star Trek” better than with his beloved young son, as Adam Nimoy writes in his new memoir, “The Most Human: Reconciling With My Father, Leonard Nimoy.”

It wasn’t until Leonard and, later, Adam, who smoked marijuana daily for 30 years, both joined 12-step programs and managed to get clean that they finally found a tentative path back to each other. But Adam Nimoy has never stopped celebrating his father and his work, including in his 2016 documentary “For the Love of Spock.”

On Saturday, Nimoy will be at the “Super 70mm Star Trek 60th Anniversary Series” at the Fine Arts Theatre Beverly Hills, where he will present his documentary and then discuss “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Kahn” with its director, Nicholas Meyer. He will then return for a more than 20-city tour to promote “The Most Human,” including many stops at Jewish community centers and temples “because there’s a whole Judaic element to Leonard Nimoy and our story,” Adam Nimoy said recently while speaking by video from his Los Angeles home about the book and his father.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Are you looking forward to presenting your documentary to an audience of passionate fans again?

As I travel around the world promoting my book, I am amazed at the love and devotion that still exists for Leonard. There has been so much produced about “Star Trek,” so my movie is just one small chapter. I am simply honoring my father and what he accomplished in life, coming as a poor kid from Boston to Hollywood and having a huge success that would impact millions of people around the world.

The title of the book focuses on your father, but the book is mostly about your recovery, your relationship with your children, and the love you found in your second marriage to Martha. How did that evolve?

My original plan was to write about recovery and my family because I had written about my father and talked about my relationship with him in the film, and I thought maybe it was time to step away from that.

My kids are always telling me, “You're your own man. Enough with Leonard and 'Star Trek.'” But they're always calling me to celebrate him and his memory. My son was playing drums at a nightclub and Jeff Goldblum came up to talk to him about his drumming and Jonah said, “You worked with my grandfather on 'Invasion of the Body Snatchers,' and they talked about him.” And my daughter works at Paramount, where Leonard's legacy is everywhere.

“The Most Human: Reconciling with My Father, Leonard Nimoy” by Adam Nomoy.

(Chicago Press Review)

I resisted it a little bit, but it was a hot topic. I was writing about my recovery and relating to my mother, my ex-wife, and my kids, but the bulk of my resentment and the most important part of my recovery was, “How do I deal with my dad?”

I've been sober for 20 years. I still tell my father's story at 12-step meetings (anonymously—these people don't know I'm Leonard Nimoy's son) and it resonates with people who have issues with their own parents. They come up to me afterwards to tell me they're inspired to try to reconcile with someone. So while I addressed these issues with my father in my first book and in my documentary, I decided to go much deeper into our relationship.

Do you think this book will change people's perspective of your father and his connection to Spock?

I still devote myself to my father and the character, and I try to be very careful with that. When I write about him I give him a lot of freedom because of his own parents and their example. These Ukrainian refugees who didn't know anything about America when he came here. I give my father a big break because he was desperate to survive. He didn't have any support base when he came to Los Angeles; it was just about surviving. So I just wasn't paying attention to the family. I'm always proud of what he accomplished and I'm just trying to add another dimension to a very complicated man.

He's flawed, he's human, and he has his own weaknesses, but if people could look at it in depth, they might feel more empathy for what he's been through. After writing the book, I feel more empathy for my father simply because of the insurmountable odds that he overcame.

I'm different from my father. Family was a priority for me, even when I was pursuing my career. But I wasn't desperate to survive, to be a self-made man. So it was easier for me to say, “I want to be successful, but my family is just as important to me.”

I had the support and financial backing of my parents; my mother is the unsung heroine of all this because she was loving, sensitive and understanding, all things my father simply was not.

It really all goes back to the idea that when I was 10, “Star Trek” came on the air; but when my father was 10, he was selling newspapers on Boston Common in the middle of winter.

Leonard Nimoy, from left, with his son Adam, his first wife Sandi and his daughter Julie.

(Adam Nimoy)

You write about his complicated relationship with William Shatner, which went from tense to extremely close and then disintegrated again. Did you ask Shatner about this while working on the book?

I know Shatner's perspective: Bill loves Leonard, period. And I love Leonard. But loving Leonard is very complicated. And Bill has his own weaknesses.

I know the whole story because my father couldn't control himself when the subject came up; he told me the whole litany and I know where all the bodies are buried. There were so many frustrations and challenges in the relationship that it's a miracle they ever got through. [had] This love relationship lasts a few years. That should be celebrated and that is where the focus should be.

And the fact is, when the camera is on, those guys look incredibly good together. It's one of the most dynamic duos in pop culture history, period.

My father had problems working with Jeff Hunter [who played Captain Pike in the 1964 “Star Trek” TV pilot] Because Jeff was a very internalized actor. But Bill is like Douglas Fairbanks: he has that style and that love of life, and he's very outgoing, so my father was able to concentrate on internalizing his character. We wouldn't have had Spock without Bill as Kirk.

Your book celebrates in detail your deep love for your second wife, Martha, who died in 2012. You later had a brief marriage to Terry Farrell, who played Jadzia Dax in “Deep Space Nine,” but you don’t mention him at all. Why?

It didn't work out and I didn't need to go there. I wanted to honor Terry and what we had by leaving it at that for the moment.

Leonard and Adam Nimoy. “Loving Leonard is very complicated,” Adam Nimoy said.

(Adam Nimoy's personal collection)

You write a lot about the places you lived, the neighborhoods you frequented, the places you went to recover, and your synagogues. To what extent did Los Angeles influence you?

The city shapes you. It's inevitable. My father, who grew up on the streets of Boston, shaped him to be a tough, determined guy who wouldn't take no for an answer and would succeed no matter what. That's part of the problem I have with my father: In Los Angeles, we have a totally different environment. It's much more relaxed. We have sunny Southern California and the beach.

Much of the book is about recovery. What struck me is that much of what you learned seems like something we should all learn, probably as children: “I am responsible for my second thought and my first action” to stop defensive reactions, and the acronym “WAIT” for “why am I talking?”

You don't have to be an addict or an alcoholic to be in recovery – everyone is recovering from something and these are just tools to cope with life as it is. This is a big part of my emotional recovery. There are many mantras that boil down to, “When someone gets on your nerves, don't say anything and let your mind relax after it has gotten out of control.”

At first, you were angry with your father because he had never made amends with you as part of his recovery. When you entered recovery, you made amends with him, which dramatically improved your relationship. Is there a part of you that still wishes he could have done that for you?

There's no way guys like him from that generation can look back and say, “Oh, I need to apologize.” It's too overwhelming. They can't just pull the rug up and look underneath it. It would devastate them. As soon as I stopped trying to prove my dad wrong, everything was fine.

And he was really there for me when Martha was sick. What more could you ask for?