As someone who grew up reading the Hardy Boys, collecting a lot of those beautiful blue spines, I love teenage detectives. Nancy Drew in “Scooby-Doo,” Shelby Woo, Hayley Mills in “The Moon-Spinners.” As for the teens and tweens these stories are nominally aimed at, this is a population in whose lives every day presents some new mystery: mysteries of the heart, mysteries of the changing body, mysteries of strange parents, mysteries of missing friends with seemingly new friends. These stories can be empowering, like spiritual krav maga.

Adapted by Poppy Cogan from British writer Holly Jackson’s popular 2019 young adult novel, “The Good Girl’s Guide to Murder,” which debuts Thursday on Netflix, is a gripping film, not so much for the plot as for the characters (which is how all detective stories live or die) and a great performance by Emma Myers (“Wednesday”) as its central detective, Pippa Fitz-Amobi. It’s less outlandish than the title might lead you to expect, but it lacks bite and much heart.

We’re in Little Kilton, a quaint English village, the kind of place where, as Miss Marple says, “you turn over a stone and you have no idea what’s going to come out of it,” and Miss Marple is rarely wrong. Five years earlier, the town was rocked by the disappearance of teenager Andie Bell (India Lillie Davies) and the confession and apparent suicide of her boyfriend, Sal Singh (Rahul Pattni). While the townspeople seem determined to put the past behind them, there’s also a large mural in their honor and what seems like a constant stream of flowers and mementos marking the shrine. So that book isn’t quite closed.

Pippa or Pip, now a senior, remembers seeing Andie and Sal on the day of her disappearance, and also that Sal was always nice to her; she doesn't believe he is someone who would kill anyone, and for her senior project, or under the cover of it, she has decided to investigate the case.

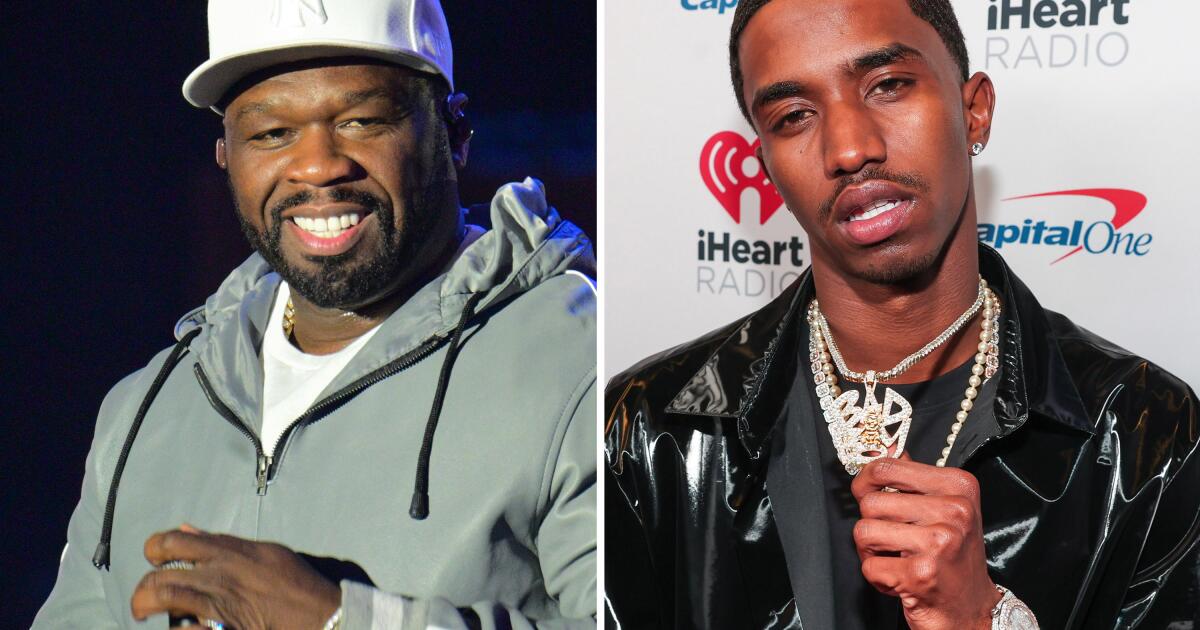

Ravi (Zain Iqbal) steps in to help Pip (Emma Myers) solve the mystery of Andie and her brother, Sal.

(Sally More/Netflix)

This connects her with Ravi (Zain Iqbal), Sal’s younger brother, who, like everyone except Pip, accepts the accepted verdict – at least, he’s put it behind him, until Pip gets her interested in him and together they become detectives: he calls her “Sarge”, as in detective sergeant, and they argue about who is Holmes and who is Watson – or more specifically, who is Cumberbatch and who is Freeman. But it’s clearly Pip who leads the way.

Pip turns her bedroom wall into a noticeboard, filled with newspaper clippings, photographs and notes to herself (it takes her mother a while to notice). Over the course of six 40-minute episodes, she moves around the city, from garden party to rave to locker room, as her “project” turns from schoolwork to amateur police work. She receives threatening notes and text messages warning her to “stop digging.” But she also has reason to question her own motives.

“I'm just trying to find out the truth,” Pip tells Andie's sister Becca (Carla Woodcock).

“It’s not about the truth,” Becca replies. “People act like this is all for the dead person, but it’s not, it’s for them.”

As the title suggests, Pip is a good girl, who doesn't exactly turn bad, but she does lie to her parents (Anna Maxwell Martin and Gary Beadle), ignore their orders, get drunk for information, and commit a fair amount of break-ins (break-ins, anyway) in order to find clues and steal evidence. Which, frankly, is good training for being a detective in crime fiction.

The cast is large, packed with siblings, friends, townspeople and parents, including Mathew Baynton, of “The Wrong Mans” and the British version of “Ghosts,” as Pip’s teacher and the father of her friend Cara (Asha Banks). But above all, it’s Myers’s show (the actor is American, which inverts the more common situation of Brits playing Yanks, but, really, he had no idea). Small and thin, with large, expressive, wide-set eyes, a forehead made for writing thoughts and the mouth of a silent-film star, at 22 she makes an entirely believable 17-year-old: scared and excited, self-assured even when she’s not. Myers is especially good at conveying a kind of shyness laced with bravado, along with varying degrees of concern that only increase as she hurtles her way through increasingly dangerous situations.

The cast of Netflix's “A Good Girl's Guide to Murder,” from left: Asha Banks as Cara Ward, Yali Topol Margalith as Lauren Gibson, Emma Myers as Pip Fitz-Amobi, Raiko Gohara as Zach Chen and Jude Morgan-Collie as Connor Reynolds.

(Sally More/Netflix)

The direction, by Dolly Wells and Tom Vaughan, is admirably direct; the show is suspenseful because it is full of suspenseful situations, not because it is overloaded with dark music, disturbing sound effects and shocking camera movements. As with the best British mysteries, we are in a real place among believable people. There is no attempt to make the teenage characters glamorous or sexy or overly adult (a couple of older-generation kids imagine they are, but it's pretty transparent). Pip's friends tend to be nerdy and late bloomers, which should make them relatable to a large segment of the show's young (and, indeed, former young) audience (I'd also hold them up as role models, but maybe that's wishful thinking). Circumstances may push them out of their comfort zone, but the writers don't push them out of it, if you know what I mean.

Not everything Pip does when faced with a problem makes much sense, but in this he has plenty of company from adult detectives. I can often be found shouting through the screen at detectives who, alone with a killer, announce that they know what they did and how they did it and therefore they must sneak out of danger once again. It's just something that goes with the job.

As for the ending (I don't want to give any spoilers), the details aren't predictable per se, but, to put it in musical terms, there's a sort of half-hearted cadence followed by a true cadence followed by a plagal cadence. You'll have guessed something from the first episode, if you have any experience with mysteries, or even the movies, though you might not have seen the rest coming, because essential information is withheld until the end, and culprits in TV mysteries are remarkably good at looking innocent. They tend not to play fair, and “Good Girl's Guide” is no exception.

I probably should have mentioned, though it should be obvious from the above, that this is also a coming-of-age story, centered on a partnership that becomes a friendship that might one day blossom into something more and which, like every cinematic romance, will run into trouble about two-thirds of the way through.

I can say, no more.