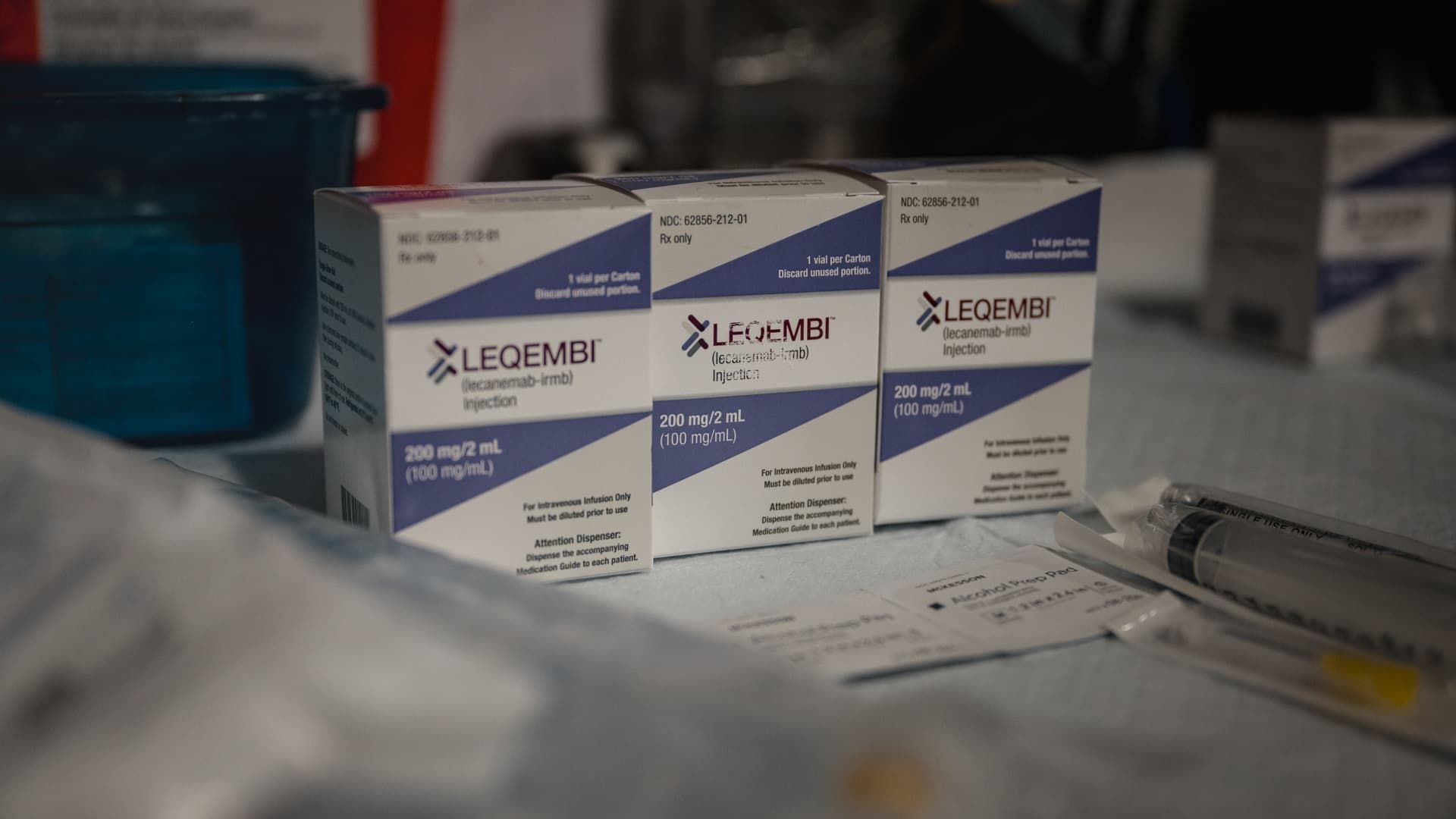

The newly FDA-approved Alzheimer's treatment, Leqembi, will be prepared at Abington Neurological Associates in Abington, Pennsylvania on Tuesday, November 7, 2023.

Hannah Yoon | The Washington Post | Getty Images

The breakthrough Alzheimer's drug Leqembi slowed the progression of the disease in patients over three years, demonstrating the need for long-term treatment, according to new data released Tuesday by Japanese drugmaker Eisai.

The results of the study on Leqembi, which Eisai shares with BiogenThe study also found that the health of Alzheimer’s patients taking the therapy worsened after stopping treatment. Rates of adverse side effects associated with Leqembi, including bleeding and brain swelling, decreased after six months of treatment, Dr. Lynn Kramer, Eisai’s clinical director of human biology deep learning, told CNBC.

That decline is critical: Those brain side effects have raised concerns among some doctors and are the main reason a European drug regulator recommended against approving Leqembi last week.

The study is the largest efficacy and safety study available to date for Leqembi, which has been rocky in its U.S. rollout since it won regulatory approval last summer due to hurdles related to requirements for diagnostic testing and regular brain scans, among other issues. Eisai published 24-month data on Leqembi in November.

Eisai presented the results Tuesday at the Alzheimer's Association International Conference in Philadelphia, the world's largest meeting for dementia research. The results are a first look at what the future might look like for Alzheimer's patients with therapies like Leqembi, which is currently taken twice a month through an infusion.

The drug is a monoclonal antibody that targets toxic brain plaques called amyloid, a hallmark of Alzheimer's, to slow the progression of the disease during its early stages. Leqembi also works by removing protofibrils, the building blocks of amyloid plaque.

The data demonstrate the importance of early and sustained treatment for people living with this notoriously difficult-to-treat brain disorder, even after a drug clears the patient's amyloid plaque.

“Continuing treatment is important if you want to maintain cognition and functionality for a longer period of time,” Kramer said.

While Leqembi is not a cure, “if you start taking it early enough, it can provide years of benefit,” he said.

Kramer added that Eisai believes patients may eventually be able to switch to a maintenance dose of Leqembi after about 18 to 24 months of treatment, which could be a less frequent or more convenient way of taking the medicine over a long period of time.

Eisai and Biogen are seeking regulatory approval for a monthly infusion of Leqembi, with a decision expected in January. The drugmakers also aim to bring to market an injectable form of Leqembi that patients can take at home once a week.

“Those two things will change the paradigm, make it easier for the patient and for the entire medical system,” Kramer said in an interview.

According to the Alzheimer's Association, nearly 7 million Americans suffer from the disease, which is the fifth leading cause of death among adults over 65. It is estimated that by 2050, the number of Alzheimer's patients in the United States will increase to nearly 13 million.

Details of the long-term study

The results are based on extensive research on selected participants in mid- and late-stage trials in Leqembi.

A phase three trial, called Clarity AD, examined three different groups of patients over 36 months.

One group of participants took Leqembi for the full three years, while another received a placebo for the first 18 months before switching to Eisai's drug for the same period of time. Eisai looked at a final group of patients outside the trial who received no treatment for three years.

Tek Image Science Image Library | Science Photo Library | Getty Images

Patients who started Leqembi early continued to benefit from the drug for three years and showed a slower rate of cognitive decline compared with the other two groups, according to a presentation by Eisai.

The difference in cognitive decline between the “early-onset” Leqembi group and patients who received nothing throughout the study period became greatest between 18 and 36 months, Kramer said.

“Leqembi interrupts the natural progression of the disease and its effect is increasing,” he explained, adding that “the earlier it is detected, the better.”

Patients who started on placebo experienced slower cognitive decline after switching to Leqembi at 18 months, but their Alzheimer's disease remained worse than that of the group that started Leqembi earlier, throughout the 36 months.

A substudy of the trial partly looked at patients who had no levels or very low levels of another protein that builds up in the brain, called tau, which is considered a marker of Alzheimer's severity. People with low levels of that protein are in the early stages of the disease.

According to the presentation, after three years of treatment with Leqembi, 59% of people with zero or very low tau levels did not notice any improvement in their Alzheimer's disease. A little more than half of that patient population actually noticed an improvement in their condition.

Meanwhile, a phase two trial, called Study 201, looked at patients who temporarily stopped taking Leqembi.

For 18 months, one group of participants took Leqembi and another received a placebo. The groups then took nothing for a rest period of two years on average before all patients began treatment with Leqembi for another 18 months.

Leqembi's positive effect on the patient's disease continued even after treatment was stopped, the presentation said.

But the rate of cognitive decline in patients who stopped taking Leqembi returned to the rate of people who had taken a placebo during the rest period. This shows that even when amyloid plaque is cleared, the disease continues to progress when a patient stops taking Leqembi, Eisai said in a statement.

“The concept is that if you stop doing it, you get worse,” Kramer said.