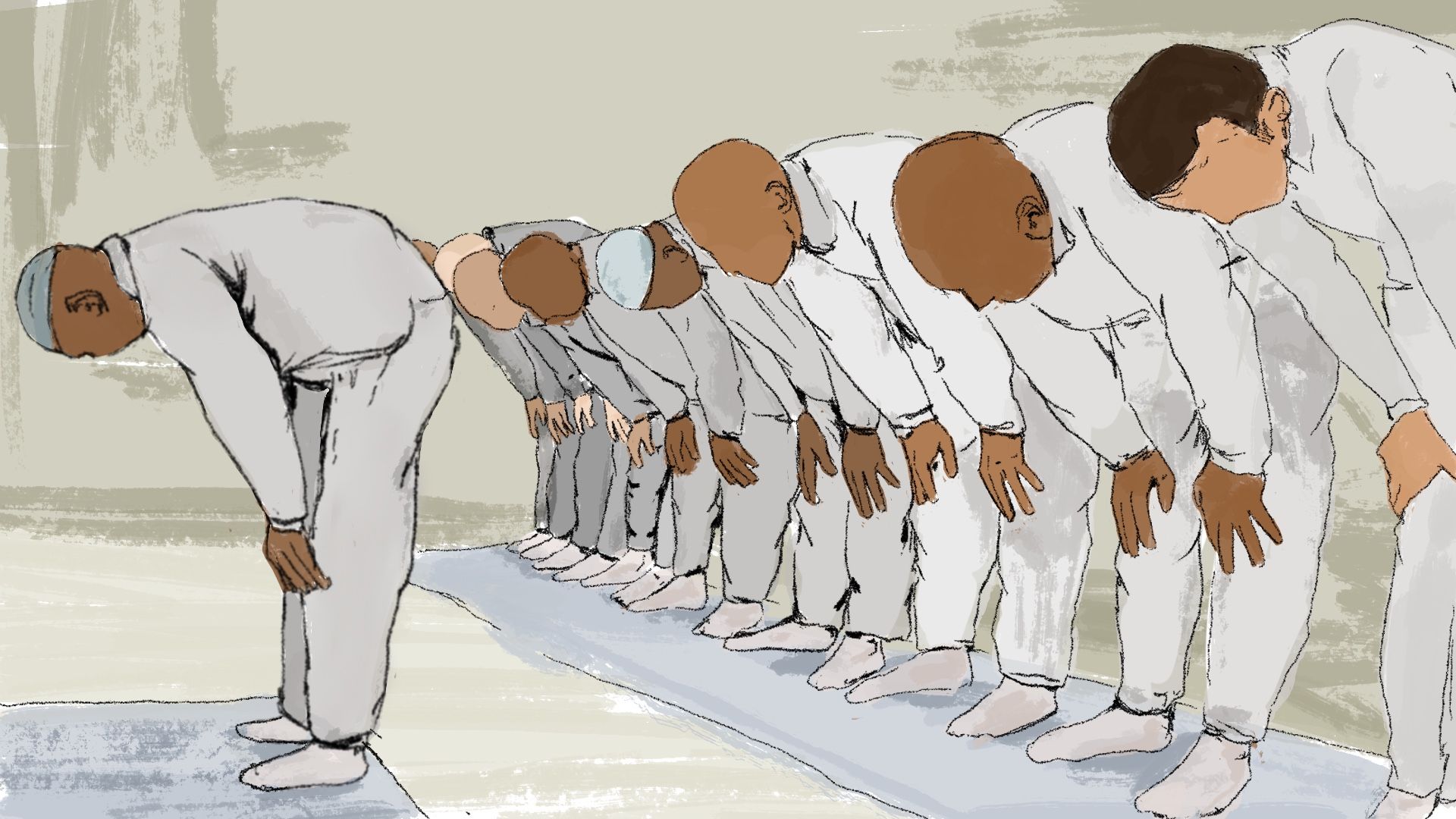

On February 28, 2021, shortly after nine p.m., nine Muslim men took off their shoes, lined up single file, and knelt silently for Isha, the obligatory nighttime prayer of their faith, inside a state prison. of Missouri in the small town of Bonne Terre.

His action was neither unusual nor provocative. The men had been praying together in the common space of their wing at the Eastern Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center (ERDCC) for several months without incident, up to four times a day, after COVID restrictions put the chapel in the prison off limits.

They lived in Housing Unit Four or the B wing of House 4, which was known as the “honor dormitory” and was reserved for prisoners with no recent infractions. In other wings of the men's prison, inmates were given limited time outside their cells. But in the honorary dormitory, the men could be out of their cells all day in the common area on the ground floor of the wing, heating food they had bought at the commissary in the shared microwave, or gathering to talk or play games. cards or chess at the tables. bolted to concrete floors.

The group of worshipers who gathered to pray in the back of the common area began with three prisoners and had grown to between nine and 14. Qadir (Reginald) Clemons, 52, who normally gave the call to prayer, He says he had checked in periodically. with the prison chaplain and the “bubble officer” in the control room, where all four wings could be seen, to confirm that there would be no problem with the group praying. Christian prisoners also held community prayer circles throughout the ERDCC, including in the honor dormitory.

That night, however, the prison guards would attack the kneeling men. Five of them would be sprayed with pepper spray until they writhed in pain. Seven would be handcuffed and, most of them barefoot, marched about 50 meters through the winter mud of a playground to another housing unit where they would be placed in solitary confinement, also called administrative segregation, AdSeg, or simply ” the hole”. .

The group's leader, Mustafa (Steven) Stafford, 58, a short, jovial man whom others called “Sheikh” because of his commitment to Islam, would be attacked on the way to AdSeg and again once there. Following his release from the Hole 10 days later, Stafford and others would face further retaliation.

None of the men, who called themselves the “Bonne Terre Seven” after the incident, were charged with anything more than disobeying a lieutenant's orders to stop praying, something their faith dictates they cannot do except in case of emergency. According to the now-retired lieutenant, no correctional officers were disciplined for the incident.

This account of the violent disruption of a peaceful prayer and its aftermath is based on dozens of in-person and telephone interviews, including six of the Bonne Terre Seven, eight other prisoners who witnessed the attack, and several officers. It is reinforced by accounts of a lawsuit filed in 2022 by Clemons, now amended to include his eight fellow worshippers, asking the court to declare that the Missouri Department of Corrections (MODOC) cannot deny their religious rights and grant them a Compensation for damages. what they suffered. It is also based on interviews with human rights and prisoner advocates and with lawyers from the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR).

The picture that emerges is of a facility, and a broader prison system, that often treats Muslim prisoners, most of whom are black, with suspicion, hostility and racism.

Even in this context, the ERDCC attack stands out for its savagery. “I have never seen a case involving this level of violence,” says Kimberly Noe-Lehenbauer, a CAIR attorney representing the nine victims.

The prison

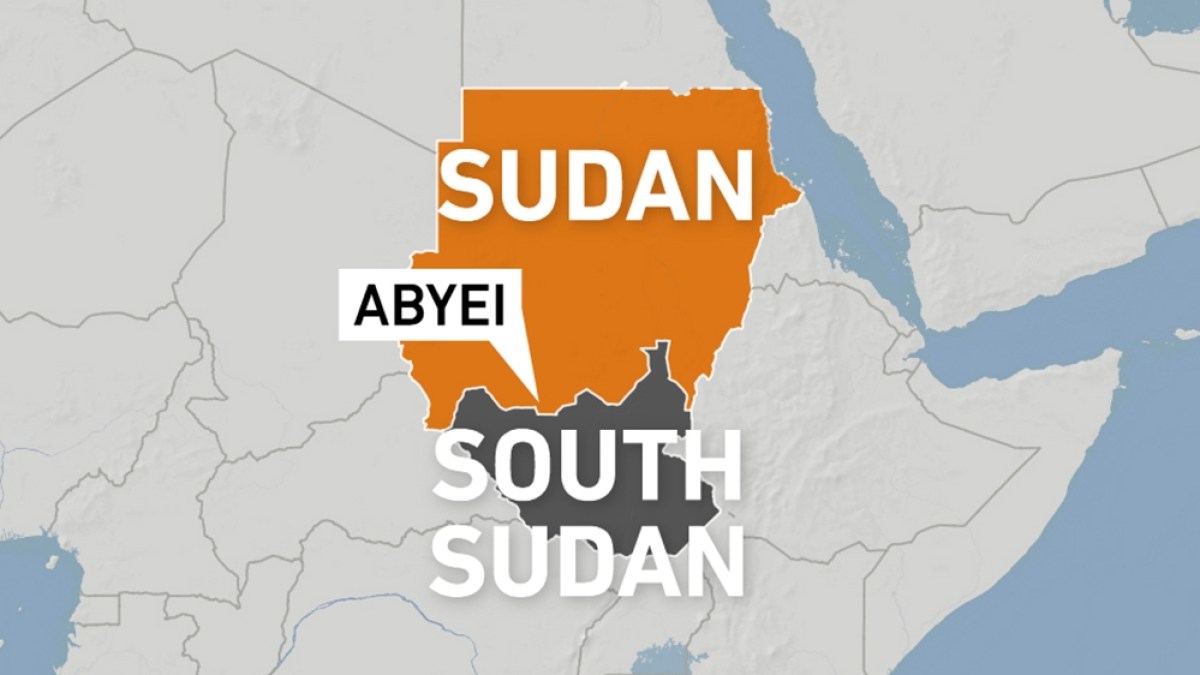

ERDCC is located outside of Bonne Terre, in the low, rolling hills of the Ozark Plateau, 60 miles (96.6 km) south of Missouri's second largest city, St Louis.

Bonne Terre is in St Francois County, which is almost 93 percent white and openly Republican; 73 percent of voters supported Donald Trump in the 2020 election. Trump signs still proliferate today, along with other markers of local beliefs; A sign reading “Jesus Loves You” sits on the side of a state highway, followed shortly by a front gate draped in the Confederate flag.

ERDCC opened its doors in 2003, bringing a major new industry to the former mining town, whose center sits atop a large mine that was closed in 1962. The town has a population of less than 7,000, including prisoners, who in July 2020 they amounted to almost 2,600. men.

ERDCC is a sprawling D-shaped mixed-security camp. It has the largest prison population in the state and encompasses 11 housing units, 10 of them with four wings and a control unit or “bubble” in the center.

The camp also has a dining hall, a building that houses educational programs and a medical center, three recreational yards, an intake area, and a small factory where some prisoners produce soap and other cleaning supplies. A visiting room is located in a building just after the prison entrance. That same building houses Missouri's only execution chamber, although condemned prisoners are held in Potosí, 15 miles (24 kilometers) to the west, and brought to the ERDCC shortly before their scheduled execution.