Days after the surprise arrest on U.S. soil of two of Mexico's most wanted fugitives, details of what exactly happened remain unclear.

Among those wondering how the powerful drug lords ended up in handcuffs at a private airport outside El Paso is Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who said this week that U.S. authorities have kept his government in the dark about the operation.

“We need more information,” he said. “We need them to tell the truth.”

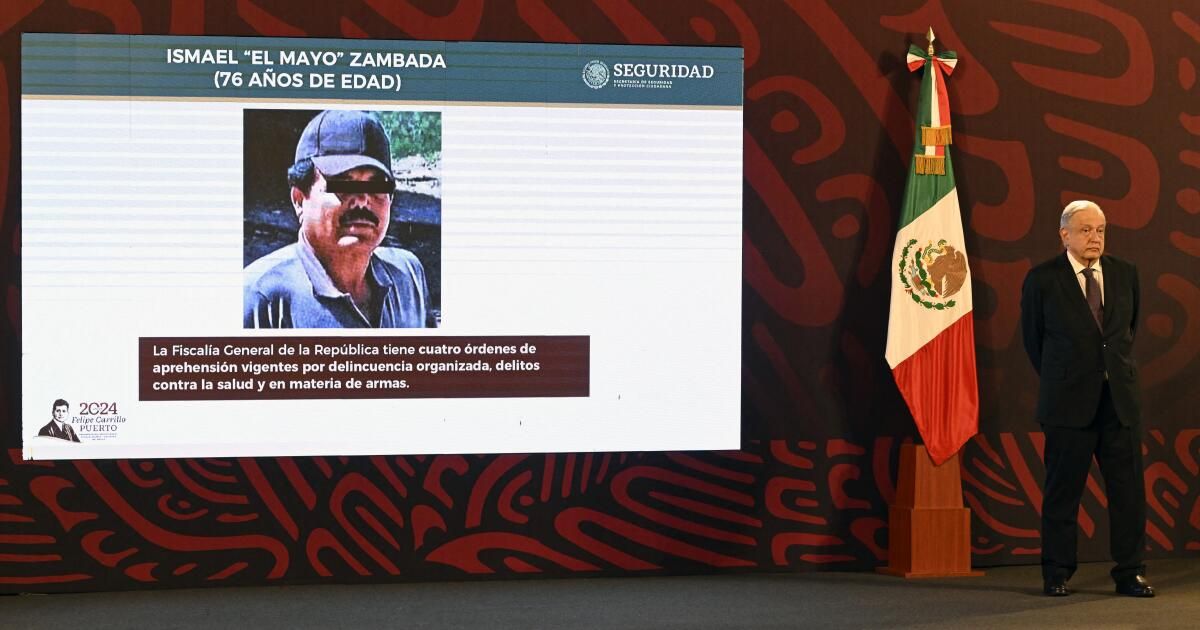

The president has been heavily criticized for being caught off guard by the capture of Sinaloa cartel leaders Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada Garcia and Joaquin Guzman Lopez, son of notorious drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman.

Mexican authorities say they were not informed about the operation until after the two suspects were arrested on July 25. They say they are still unsure whether the version of the incident offered by Zambada’s lawyer — that Zambada, 76, was kidnapped by Guzmán López and handed over to U.S. authorities — is actually true.

The fact that Mexican officials still know so little about a major law enforcement operation carried out by a close ally against two of its citizens underscores how much security cooperation between the two nations has deteriorated under López Obrador, who has fiercely defended Mexican sovereignty and regularly criticized U.S. officials for overstepping their authority on Mexican soil.

Trust between the two countries has been shaky since 2020, when former Mexican Defense Secretary Salvador Cienfuegos was arrested at Los Angeles International Airport on suspicion of drug trafficking. López Obrador, who said he had not been briefed on the investigation, persuaded the Trump administration to return Cienfuegos to Mexico, where he was released and later awarded a top military decoration by the president.

The Cienfuegos case — in which López Obrador called the US evidence “garbage” — strained relations between the United States and Mexico.

DEA agents complain that local authorities have hampered their work in Mexico. U.S. officials also complain that Mexico is not doing enough to counter fentanyl trafficking and have criticized López Obrador for incorrectly insisting that the synthetic opioid is not produced in Mexico.

López Obrador, for his part, accused the US government of “espionage” and “abusive interference” after the DEA announced that it had infiltrated the faction of the Sinaloa cartel known as Los Chapitos, alleged drug lords who are sons of the imprisoned El Chapo and specialize in fentanyl smuggling.

Cecilia Farfán-Méndez, a researcher at the Institute for Global Conflict and Cooperation, said “there is very little bilateral work” between the two nations despite a recently renegotiated plan for security cooperation. Press releases touting cross-border police collaboration, she said, were mostly for show.

“What is happening at the operational level has been left very empty,” he said.

For many Mexicans, the reason behind the American silence in the recent case is humiliating but understandable: American officials simply do not trust their Mexican counterparts in a nation where cartels control vast swathes of territory and have long bribed local police, mayors and high-ranking officials.

“The gringos were not going to trust the Mexican government for such a delicate, historic and sensitive operation,” wrote columnist Carlos Marín in the Mexican newspaper Milenio. Marín, mocking the Mexican investigation into the matter, continued: “What is the Attorney General of the Republic going to do… ask for the extradition of the American agents who planned and executed this singular feat?”

A long list of cases against corrupt Mexican police authorities attests to the reasons behind Washington's lack of trust.

In the latest sensational case, Genaro Garcia Luna, Mexico's former security chief and face of the drug war, was convicted last year in U.S. District Court in Brooklyn of accepting millions of dollars in bribes from the Sinaloa cartel.

Derek Maltz, a former head of the DEA's special operations division, said he had no access to information about the arrests of Zambada and Guzmán López but was not surprised to hear Mexican officials say they had been kept in the dark.

“It’s a very delicate situation,” Maltz said. “We know that the Mexican government is super corrupt and that high-level operations have been at risk for years.”

Maltz noted how for years Zambada's former partner, “El Chapo” Guzmán, escaped police control after U.S. officials shared detailed information about his whereabouts with their Mexican counterparts.

“We would call him Houdini,” Maltz said. “He would get away with every attempt at the last minute. Obviously, they were on the payroll. Things haven’t changed. Mexican officials are on the payroll and constantly monitoring U.S. law enforcement efforts to hunt down the kingpins.”

Maltz said that even with the near misses and alleged leaks, there was little U.S. agents could do because they were operating in a foreign country. Guzman was eventually captured by Mexican special forces in 2016, extradited and sentenced to life in a U.S. prison.

What exactly happened on July 25 remains unclear and full of intrigue.

What is clear is that Zambada and Guzman Lopez were aboard a plane that took off from somewhere in Mexico and landed Thursday at a small airport in rural New Mexico, just across the Texas state line from El Paso. U.S. officials initially said Zambada had been tricked into getting on the plane. But Zambada’s lawyer later claimed that Guzman Lopez had forced Zambada aboard and tied him up — essentially kidnapped him.

Speculation has been rife in Mexico that Guzman Lopez was seeking to hand over the elderly rival kingpin in hopes of winning clemency for himself and his younger brother, Ovidio, who is also in federal custody in the United States on drug trafficking charges. But Guzman Lopez's lawyer told reporters in Chicago on Tuesday that his client has no deal with federal prosecutors.

“You ask if it was a surrender, if it was a capture,” Rosa Icela Rodriguez, Mexico’s security secretary, told reporters. “That is part of the investigation and part of the information that we would be waiting for from the United States government.”

Linthicum and McDonnell reported from Mexico City, Hamilton from San Francisco. Times staff writer Cecilia Sánchez Vidal in Mexico City contributed to this report.