It’s the morning after the night before and the UK has a new government. Keir Starmer’s Labour Party has won the general election in a landslide, securing almost as many seats and as large a majority as Tony Blair’s “New Labour” achieved in 1997.

However, the fact that Starmer’s Labour Party has finally come to power after 14 years of prolonged and overwhelmingly catastrophic Tory rule is not all there is to know. As always, the small print matters and demands careful analysis.

Labour, it seems, owes much of its landslide victory not to the electorate's embrace of Starmerism, but to its complete rejection of the Tories.

Last night the Conservatives were defeated, with people refusing to vote for them even in some of the constituencies long regarded as the safest, including those held by former Prime Ministers Theresa May, Boris Johnson, David Cameron and the shortest-serving Prime Minister in British political history, Liz Truss.

With the Conservatives losing a shock 250 seats, many senior figures in the party including Jacob Reece Mogg, Penny Mordaunt and Grant Shapps have been thrown out of work this morning. A record 11 former Conservative cabinet members have lost their parliamentary seats. It was a total defeat for the Conservatives.

Labour has won a landslide victory, but only a third of voters (35 per cent) voted for the party. Its share of the vote in this election is up just 1.4 percentage points compared to 2019, largely thanks to victories against the SNP in Scotland, and five percentage points less than what it won under Jeremy Corbyn in 2017.

If the British public had rejected the Tories in 2017 or 2019 in the same way as they did yesterday, Corbyn’s Labour Party would have achieved a victory as big as the one we are witnessing today.

This, of course, is a consequence of Britain's archaic first-past-the-post electoral system, which helps maintain a two-party duopoly at Westminster and often produces results that do not conform to the will of the people.

Yet despite this broken system, voters sent a clear message to Labour by electing independents.

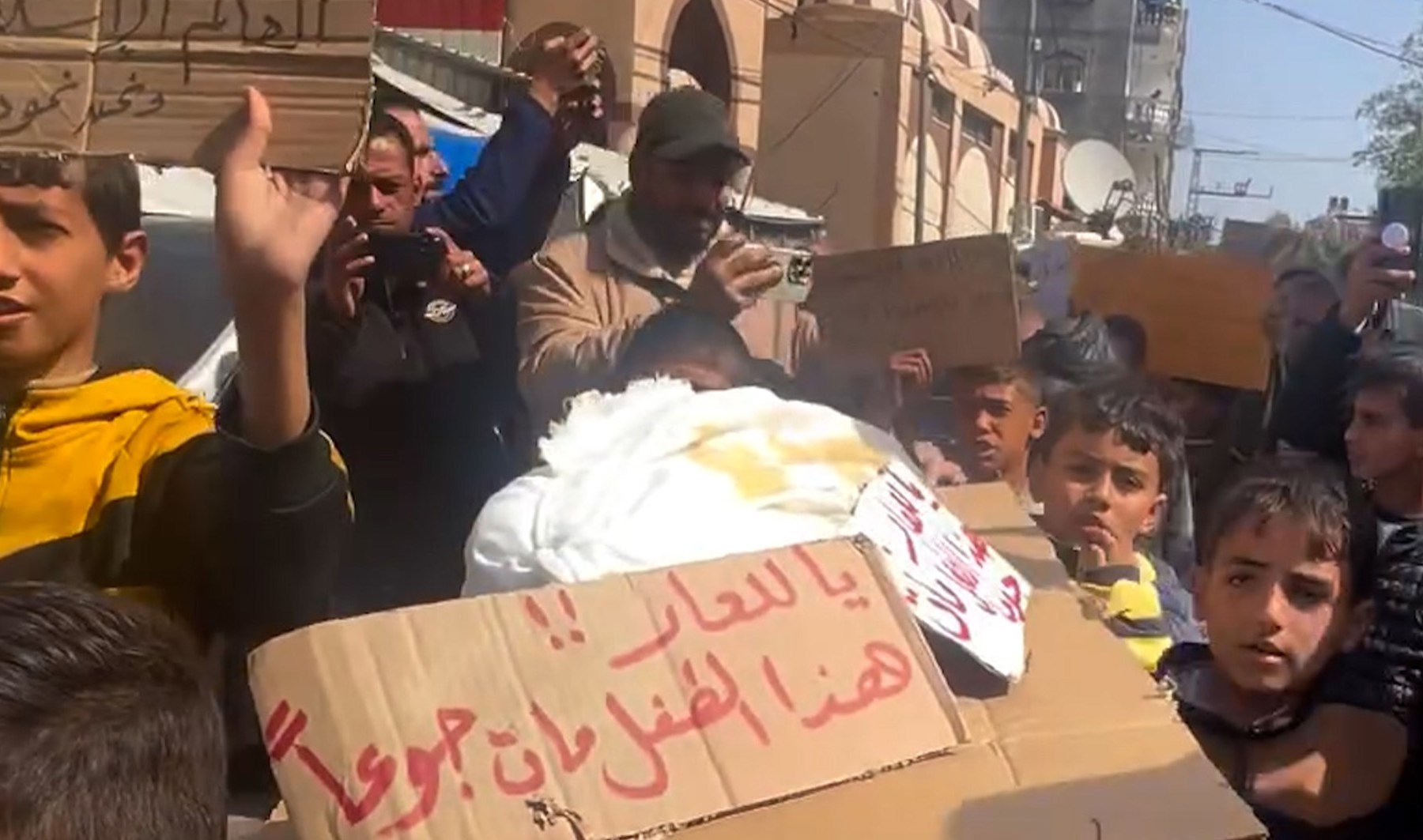

In this election, Starmer’s Labour Party has lost several of its former strongholds to independent candidates campaigning on pro-Palestinian platforms, demanding an immediate and unconditional ceasefire in Gaza and an end to the decades-long occupation of Palestine. In five constituencies, voters, concerned about Starmer’s pro-Israeli position on the war in Gaza, elected candidates who campaigned primarily on this issue. Deposed former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, for example, comfortably won his North Islington constituency as a pro-Palestinian independent.

Several other pro-Palestine independents have significantly reduced Labour’s majority in seats previously considered safe. For example, Labour’s shadow health secretary Wes Streeting’s 5,000-vote majority in Ilford North was reduced to just 500 when a 23-year-old British Palestinian woman, Leanne Mohammed, came close to unseating him. Similarly, Jess Philipps, who once had a majority of 10,000 votes, won by just a few hundred votes in Birmingham Yardley against a pro-Palestine candidate from a small party.

So far, the mainstream media has justified this unprecedented rise in the independent vote as simply a rejection of Starmer’s Gaza policy in “Muslim-majority” areas. However, this is a short-sighted analysis that implies that only Muslims care about genocide. It also feeds into clichés about the supposedly divided loyalties of British Muslims, fuelling Islamophobia.

The truth, of course, is simple. Many Britons, Muslim or not, want the killing to stop and justice to prevail in Palestine. They also want their representatives to have the moral integrity to speak out against genocide and other flagrant violations of international law, even when those violations are committed by a state that is considered a key strategic ally of the United Kingdom. Moreover, many Britons recognize the United Kingdom’s historical complicity in the violent dispossession of Palestinians from their land, and they want their government to take a principled stand on the issue to make up for past wrongs. That is why Labour’s position on Gaza led so many voters to turn their backs on the party.

Another important finding of this election was the rise of the far-right, anti-immigration Reform Party, which won 14 per cent of the vote and four seats in Parliament. Nigel Farage, former UKIP leader and leading Brexiteer, is now the Reform MP for Clacton.

In recent years, Farage has played a major role in shaping British politics, especially on issues such as immigration and the UK's relationship with Europe, despite not having a seat in Parliament. Now that he is an elected representative, it is reasonable to expect him to have an even more prominent impact.

From parliament, Reform will put pressure on Labour to adopt more right-wing and aggressive immigration policies. Starmer will have to resist this pressure and work to create an immigration and asylum policy that is aligned with international law and moral decency, and that also meets the needs of the country.

So where do we go from here?

Fourteen years of Conservative rule have been very hard on the British people. Our lives are much harder now. Many of us are much poorer. All our public services are in crisis. And, as the success of the pro-Palestine independents has shown, many of us are appalled to have witnessed our government supporting a genocidal war against a people living under occupation, whose fate colonial Britain helped seal.

There is a huge desire for change, which is why people voted against the Conservatives. But as he takes the helm of the country, it is vitally important for Keir Starmer to recognise that his victory was not absolute and that he has not convinced large sections of the electorate that his government will serve their interests. He will have to show us all that he has understood the clear message that the electorate has sent: “We reject the Conservatives, but that does not mean that we unconditionally support their Labour Party.”

In his first speech as the new leader of the United Kingdom, Starmer has indicated that he understands this and has affirmed that he wants to be the prime minister of the whole country, and especially of those who did not vote for him.

If he is serious about this – and I hope he is for the sake of our country – he will have to reach out to those on the Labour left whom he expelled from the party, to the trade union movement and to all the other forces in the UK who want to see this country serve the interests of all its people while upholding human rights and international law in its foreign policy.

The gains made by independents and candidates from smaller left-wing parties cannot be ignored. Starmer will have to listen to their concerns on issues such as Gaza and climate change, and take appropriate action. Otherwise, his election victory, based on the collapse of the Tories, will prove meaningless. Not only will he find himself unable to resist pressure from the Reform Party, but he will also face further outrage, protests and increased pressure to hold the left to account.

The pro-Palestinian left had a significant impact on this election, but the fight is far from over. Now that the Conservatives have lost power and the Labour Party is in power, this heterogeneous group needs to unite more and develop new strategies to pressure the new government to take meaningful action on issues that matter to them, starting with the war in Gaza.

This election has shown that the days of the two-party duopoly in the UK are over. With more and more people deciding who to vote for based on their values rather than party loyalty, the left has a significant opportunity to increase its impact.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of Al Jazeera.