The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum turned 85 on Wednesday, and the family of legendary Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley sent a meaningful and generous birthday gift to Cooperstown, New York.

Seventy grueling boxes of documents and photographs make up the Walter O'Malley Files, providing a road map of the Dodgers franchise from Brooklyn, New York, to Los Angeles, to annual spring training in Vero Beach, Florida.

The ever-optimistic, cigar-chomping O'Malley owned the Dodgers from 1944 until his death in 1979 and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2008. The archive was assembled and curated by Peter O'Malley and Terry O' Malley Seidler, Walter O'Malley's son and daughter who assumed leadership of the franchise after their father's death.

“There's a lot of stuff in those boxes, a lot of paper,” Peter O'Malley told the Times. “I know what's there. In my opinion, it is an extraordinary collection. It is about the franchise under his command, as well as information about him.”

Walter O'Malley, owner of the Dodgers from 1944 until his death in 1979, appears with his wife, Kay.

(National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Doing all that role justice will take time, and that's just what the Hall of Fame can offer. Known primarily for its lavish memorabilia displays that tell the stories of baseball greats and the history of the game, the Hall of Fame also includes a research library containing more than 3 million documents, 250,000 photographs and 16,000 hours of media engravings.

Peter O'Malley, 86, said he has long admired the Hall of Fame and, while downsizing from a home office last year, concluded that his father's meticulously preserved and curated archives should reside in Cooperstown.

“We asked ourselves, 'Okay, what are we going to do with all this?'” Peter said. “I'm a big fan of the Hall of Fame. “It is an extraordinary treasure and we made the decision that everything belongs there.”

Peter received an enthusiastic response from Hall of Fame President Josh Rawitch, whose career began in the Dodgers' media relations department. The idea of obtaining a Hall of Fame executive's files in pristine condition was exciting.

“When you see newspapers up close and in person, you see what [Walter O’Malley] what he was like as a person and what the world was like in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s,” Rawich said.

Of particular interest is O'Malley's handwritten and typed correspondence in a pre-digital era: his efforts to keep the franchise in Brooklyn amid an ultimately thwarted plan to build a domed stadium there; the politics of his bold idea to move the team to Los Angeles and build Dodger Stadium in Chavez Ravine; breaking the color barrier with the signature of not only Jackie Robinson but also Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Maury Wills and other black players; the creation of Dodgertown in Vero Beach, the first fully integrated spring training facility in the South; and developing relationships with Japanese baseball executives through repeat visits, including twice transporting the entire Dodger team across the Pacific for goodwill displays.

Also inside the boxes are O'Malley's appointment books from 1934 to 1979.

“It's a common thread and absolutely amazing,” Peter said. “In 1934, he bought a diary and, from then on, every year he bought another one that was identical except for the year on the cover. Everything he did, every meeting, every phone call, was documented.”

Not everything is as dry as agendas. Long before text messages and email, personal letters were the preferred way to communicate with friends and business associates. The missives to and from O'Malley with a wide range of baseball and showbiz elites (Babe Ruth, Casey Stengel, Frank Sinatra, Johnny Carson and Milton Berle, to name just a few) are mostly brief and often to the point. , and resemble text messages without emojis. but with the same number of misspelled words.

“We didn't know anyone in California when we moved here,” Peter said. “The sense of humor in the letters he exchanged with politicians, actors, writers and baseball people helped him make friends.”

The Dodgers have their own archival collection of items owned by O'Malley and much of it is displayed throughout Dodger Stadium, but primarily at the club level behind the press box. Although there is some crossover, O'Malley's gift to the Hall of Fame is primarily personal correspondence, while the Dodgers maintained ownership of the business correspondence.

All of this should shed light on the commanding presence of O'Malley, who was beloved by Dodgers players, staff and fans for his compassionate leadership and attention to detail. However, he was vilified in Brooklyn and accused of moving “Dem Bums” to Los Angeles.

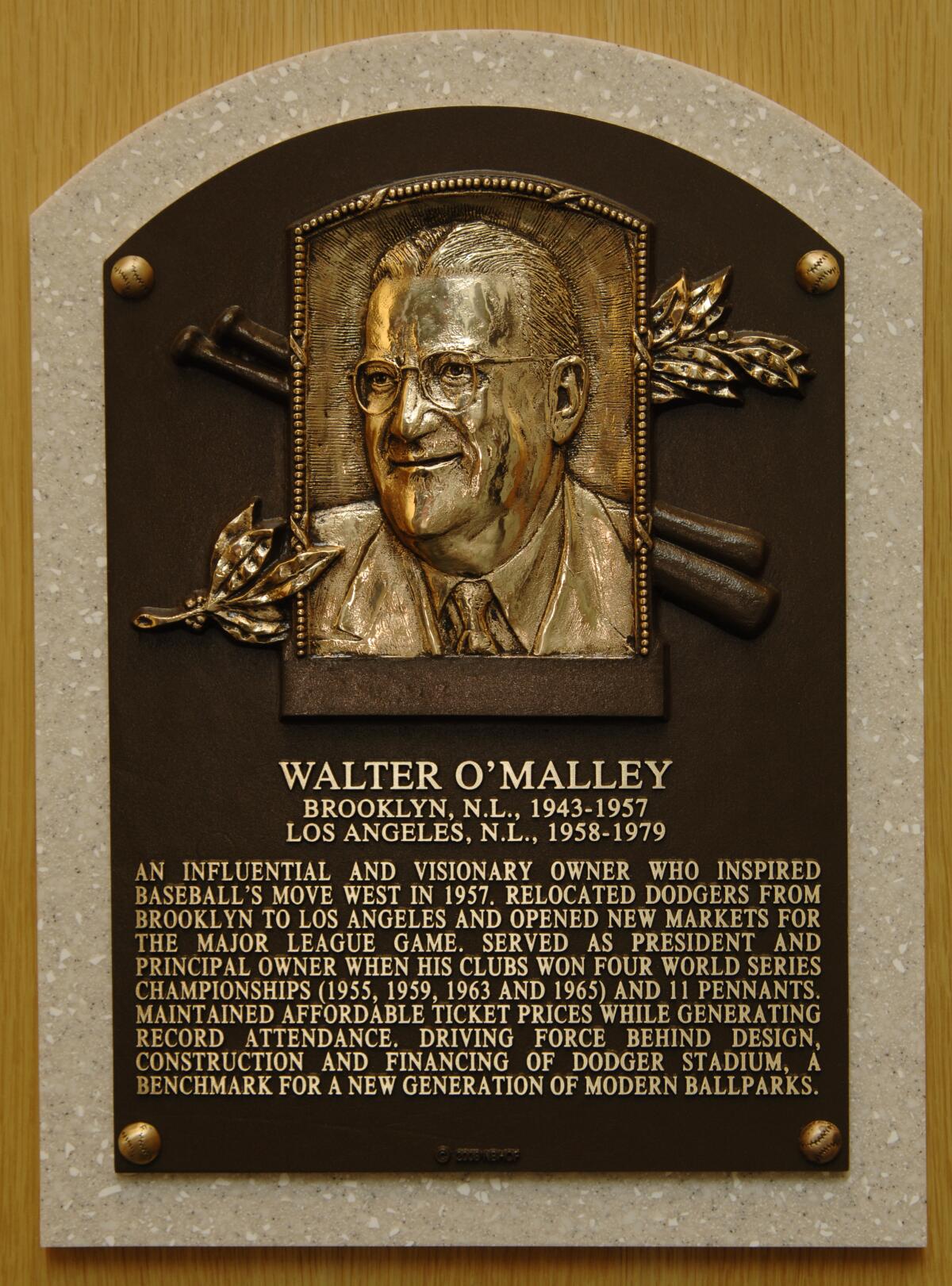

Walter O'Malley has a plaque at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

(National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Explaining why one of the most influential owners in baseball history was not elected to the Hall of Fame until nearly 30 years after his death, Peter pointed to lingering resentment over the Dodgers' departure from Brooklyn. He believes the documents in the archives tell a different story.

“I don't think anyone has worked harder than him to keep his franchise in the original city,” Peter said.

O'Malley and the Dodgers were welcomed in Los Angeles, although the way Chavez Ravine became the site of Dodger Stadium is a stain on the city's history. The area was populated primarily by low-income Mexican Americans who, due to discriminatory practices, had been prohibited from living elsewhere in the city. In 1950, eight years before the Dodgers moved from Brooklyn, Los Angeles housing officials decided to turn the area into a huge public housing project and forced existing residents to move by purchasing their homes with cash offers below from the market or taking property through eminent domain proceedings. .

When the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles before the 1958 season, the public housing plan had collapsed and Chavez Ravine was empty. O'Malley saw it as an attractive location to build a baseball stadium, reached a favorable agreement with the city, and secured a referendum vote on June 3, 1958, which passed narrowly. Dodger Stadium opened in 1962.

Peter O'Malley believes his father's files help decipher the sequence of events that resulted in the stadium being built on land unfairly taken by the city years before the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles.

“Chavez Ravine, the facts are the facts and we have the facts,” he said. “Especially today, that's appropriate. He [other MLB] The owners gave him approval to move. The records show that he was thinking about Wrigley Field or the Coliseum or the Rose Bowl, and the public housing issue occurred long before he had heard of Chavez Ravine.”

Academics, historians and simple baseball fans will have ample opportunity to examine each document in those 70 boxes. The Hall of Fame invites everyone to visit and stay a while.

“We are honored to accept this remarkable donation and are grateful in many ways to the O'Malley/Seidler family for their long-standing support of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum,” said the Hall's board president. of Fame, Jane Forbes Clark.

“During Walter O'Malley's stewardship of the Dodgers, the franchise was at the center of many of baseball's most historic moments on and off the field. … [The archives will give] researchers and historians a first-hand look at the events that changed the face of the game.”