WASHINGTON- Before being re-elected, President Trump openly threatened to use (or abuse) his power by ordering federal prosecutors to pursue criminal cases against those he considers enemies.

There are few legal provisions that can stop it.

That's because the Supreme Court has made clear that the Constitution gives the president complete authority over how to enforce federal law.

Since the Watergate scandal of the early 1970s, the Justice Department has tried to separate law enforcement from politics and keep the White House at arm's length.

But that separation is a matter of department policy, not law.

“It is the norm and the custom. It's included in the U.S. attorney's handbook,” said Washington attorney Stuart Gerson, former acting U.S. attorney general. “But under the 'unitary executive' theory, it is not illegal for the president to intervene in individual cases. “It’s just a terrible idea.”

The late Justice Antonin Scalia popularized the unitary executive theory and dissented in 1988 when the court upheld the independent attorneys that had been created by Congress.

Scalia believed that the Constitution placed all executive power in the hands of the president and that neither Congress nor the courts could interfere.

That view was adopted by the Supreme Court in July when the 6-3 majority said Trump and other presidents generally are immune from criminal charges for abuse of official power.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. singled out law enforcement and the Department of Justice.

“Investigative and prosecutorial decision-making is the special purview of the Executive Branch, and the Constitution vests all executive power in the president,” he wrote in Trump v. USA.

He said that “the president occupies a unique position in the constitutional scheme, the only person who alone composes a branch of the government.”

As head of the executive branch, the president “has exclusive authority and absolute discretion to decide which crimes to investigate and prosecute,” he declared.

Even if Trump lost the election, that opinion could have shielded the former president from much of the pending criminal case over his alleged scheme to reverse his 2020 election loss.

Now the court's opinion gives him a blank check for a second term. He would be largely free to pursue his enemies using the powers of federal investigators and prosecutors.

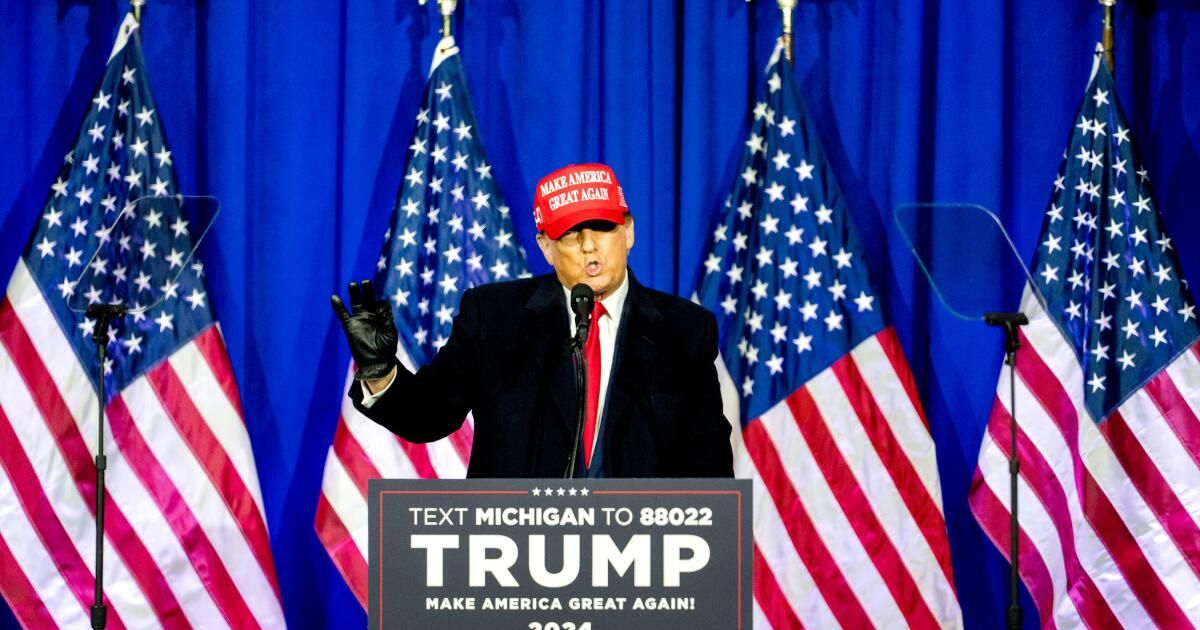

In campaign rallies and social media posts, Trump threatened to go after his political enemies if he returned to the White House.

Last year, after being indicted by the Biden administration's special counsel, Trump said he would “appoint a real special counsel to go after the most corrupt president” in US history: “Joe Biden and the entire Biden crime family.” .

He said Vice President Kamala Harris should be impeached and prosecuted. He said former Wyoming Republican Rep. Liz Cheney could be charged with treason and that critics of the Supreme Court “should be jailed.”

That doesn't mean Trump will follow through on his threats. Some of his aides and advisers say that Trump has been the victim of “weaponized” prosecutions by Democrats, and that he does not plan to carry out a campaign of revenge from the Justice Department.

“President Trump will not use the Department of Justice for political purposes, that is, he will go after people simply because they are political opponents,” Mark Paoletta, a Washington lawyer and longtime friend of Justice Clarence Thomas, wrote in a social media post. .

Paoletta, who served in Trump's first term, has been mentioned as a candidate for attorney general.

He cited the court's opinion in July as confirmation that the president's broad power to control the Justice Department includes intervening in individual cases.

“The president has a duty to oversee the types of cases the Justice Department should focus on and can intervene to direct the Justice Department in specific cases,” he said.

Legal experts see danger in politically driven investigations.

“There are reasons to be alarmed. “The president could send a list to the Justice Department of people he wants investigated,” said Peter Shane, a law professor at New York University. “Trump would think he has the right to do that. And your advisors will tell you that you have a constitutional right to do so.”

Prosecutions require proof of a criminal offense. And judges can dismiss charges that do not allege a true crime.

But Shane said the danger is not so much “a conviction or going to trial.” It is the investigation itself.”

Veteran Washington attorney Michael Bromwich agreed. “This will scare people. “It is a very effective scare tactic,” he said.

He knows this from first-hand experience. He represented Andrew McCabe, the former FBI deputy director who was fired by Trump and subjected to a lengthy criminal investigation.

“They went after him because Trump didn't like him. But in the end, a grand jury did not indict him,” Bromwich said.

Bromwich, a former federal prosecutor and Justice Department inspector general, said Trump's second term “will test the mettle” of prosecutors and judges.

“It's part of the culture of the Department of Justice,” he said. “Oaths are taken to defend the Constitution and it is well understood that cases are pursued based on the facts and the law, not for partisan or political reasons.”

He said Justice Department lawyers will face a test of their oath.

“Are you pursuing something because of the president's personal grievances?” said. “Do you ignore your oath? And if they say no, will they be fired? “They will test the mettle of prosecutors throughout the Department of Justice.”