Less than six weeks into office, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador may be acting like a lame duck.

Instead, he is using his final days in power to try to radically reform the country's judicial system, pushing through a controversial proposal that has sparked a cross-border war of words and prompted thousands of judges and other court employees to walk off the job in protest this week.

López Obrador has proposed sweeping changes under which federal judges, including members of the Supreme Court, would lose their jobs and their replacements would be elected by popular vote.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador stands at the National Palace during a ceremony in Mexico City.

(Marco Ugarte / Associated Press)

López Obrador says the reform is necessary because the courts, which have ruled against several of his major legislative efforts, are corrupt. Critics say there is little evidence of that and insist that putting judges on the country’s top courts up for election would politicize the judiciary and give even more power to López Obrador’s ruling Morena party. Having swept elections in recent years, the party would almost certainly have outsized influence over which judges would win.

The president's proposal has spooked markets, with the peso losing value against the dollar and U.S. banks including Morgan Stanley, Bank of America and Fitch Ratings warning the plan carries financial risks for Mexico and could cripple bilateral trade.

U.S. Ambassador Ken Salazar, who has had a friendly relationship with Lopez Obrador, said in an unusually terse critique Thursday that the review “would threaten the historic trade relationship we have built, which is based on investor confidence in Mexico’s legal framework.”

“Direct elections would also make it easier for cartels and other malicious actors to take advantage of politically motivated and inexperienced judges,” he added.

Salazar, a lawyer who served as Colorado's attorney general, warned that Mexico could become like Iraq, Afghanistan or other countries “without a strong, independent and corruption-free judiciary.”

“Based on my lifelong experience supporting the rule of law, I believe that the direct popular election of judges is a significant risk to the functioning of democracy in Mexico,” he said.

On Friday, López Obrador responded by calling Salazar's comments “disrespectful.”

Mexico, he said, will send a diplomatic letter to the United States complaining that the ambassador's comments “represent unacceptable interference, a violation of Mexico's sovereignty.”

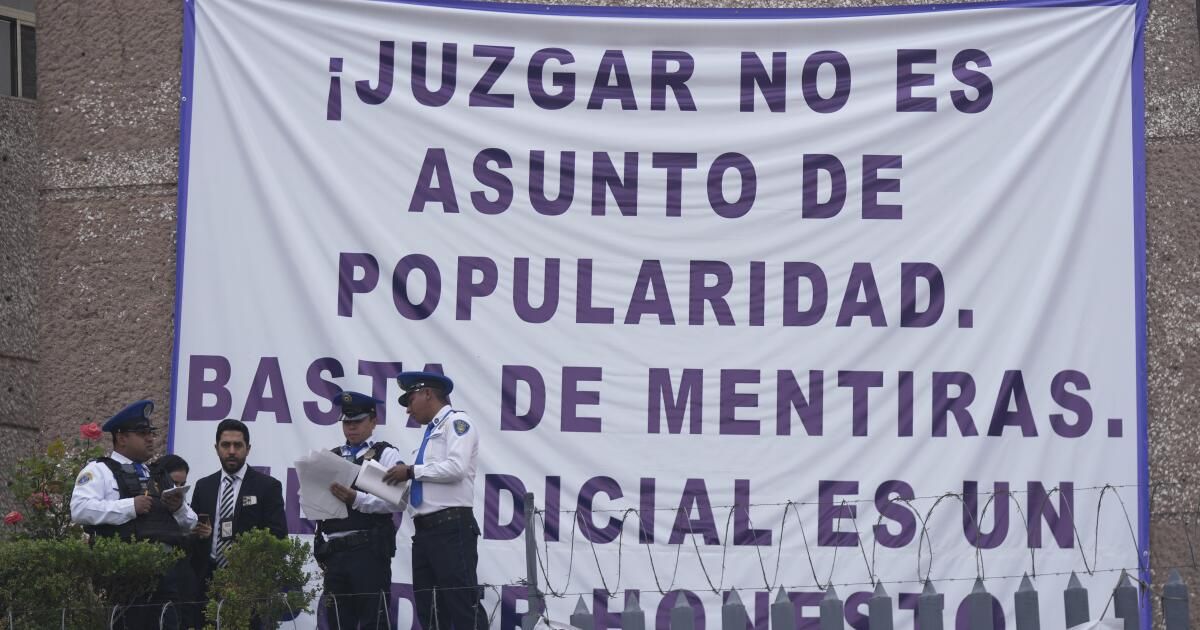

Mexico’s federal judges and magistrates decided to suspend their work starting Wednesday morning and indefinitely in protest against the proposal. Outside the closed headquarters of the federal judiciary in the nation’s capital, they have gathered daily, waving Mexican flags and carrying signs that read: “The judiciary is an honest power.”

Many said their protest was aimed not only at saving their jobs but also at protecting the independence of the country's courts.

“The strike was the only option we had left to defend ourselves as workers, to defend our jobs, our professional careers that we have been building for years,” said Roberto Díaz Cantú, 42, a lawyer who has worked in the judiciary for 14 years.

“But it is also about defending democracy, the separation of powers and the rule of law,” he continued. “We hope that people understand that an independent and capable judiciary is more important than a presidential whim.”

López Obrador first proposed the reform in February after several of his signature legislative initiatives, including major changes to the country’s electoral institute, were stymied by Supreme Court rulings. The populist leader ridiculed the judges on the country’s top court as part of a “power mafia” and said they and other members of the judiciary should be elected just like the president or senators.

López Obrador and his allies have also sought to blame the judiciary for Mexico’s high rates of impunity in criminal cases, but experts link impunity primarily to corruption and sloppy work by police and prosecutors — two branches of law enforcement that López Obrador has not proposed reforming.

For many months, the reform desired by the president seemed dead because his party did not have the necessary votes in Congress to make the necessary constitutional changes.

Claudia Sheinbaum greets supporters during a rally in Guadalajara.

(Ulises Ruiz / AFP via Getty Images)

That changed in June, when Morena won a landslide in a national election that was widely seen as a referendum on López Obrador’s six-year term. Claudia Sheinbaum, a former mayor of Mexico City and a political protégé of López Obrador, outperformed her closest competitor in the presidential election by 32 points.

By the time he is sworn in on Oct. 1, the Morena coalition will have a supermajority in the Chamber of Deputies and a simple majority in the Senate. It will control 24 of the 32 governorships and hold supermajorities in at least 21 of the 32 state legislatures.

The new Congress will take office on September 1. López Obrador hopes to take advantage of a month of a new Congress dominated by Morena to push for judicial reform.

Sheinbaum, who analysts are watching closely to see how faithful she is to López Obrador’s agenda, has said she also supports the reform. At a news conference this week, she said financial institutions should not worry.

“We will have a better justice system in Mexico,” he said. “Your investments will be even more protected.”

Orlando Ruiz Rodríguez, a 37-year-old Supreme Court worker, said he was disappointed that Sheinbaum wasn’t acting more independently. “It’s a shame that the new president doesn’t exercise her leadership and allows the current president to give her orders and let herself be controlled,” he said. “Is she that afraid of President López Obrador?”

Ruiz said he feared the proposed changes to the judiciary could take Mexico back to its pre-democratic era, when a single political party controlled most of the state for more than 70 years.

“If we do not fight this battle, our country will go back decades in terms of justice and we will once again be in the hands of a few who make decisions as they please,” he said. “It is true that improvements are needed, that reforms are needed to help us strengthen the judicial system, but reforms are one thing and wanting the total destruction of the autonomy of the judiciary is another.”

Special correspondent Cecilia Sánchez Vidal in Mexico City contributed to this report.