The Supreme Court on Thursday refused to impose new limits on corporate wealth taxes.

In a setback for anti-tax conservatives, the justices upheld a provision of a 2017 tax law that imposed a flat tax on the profits of foreign corporations whose shares were owned by Americans.

The vote was 7 to 2.

The court's decision was limited and avoided ruling on the estate tax issue.

It left unresolved a lingering dispute over whether constitutional approval of income taxes includes shares of corporate wealth or is instead limited to “realized” profits such as salaries and stock dividends.

“So the precise, narrow question the court addresses today is whether Congress can attribute the realized and undistributed income of an entity to the shareholders or partners of the entity, and then tax the shareholders or partners on their portions of those income,” said Judge Brett M. Kavanaugh. He wrote for the majority. “This court's long-standing precedents, reflected and reinforced by Congress's long-standing practice, establish that the answer is yes.”

Some conservatives fear that a future Congress led by progressive Democrats will tax accumulated wealth.

They urged the court to hear the case Moore v. United States and rule that Congress cannot impose a tax on “property or wealth.”

What was at stake in the case was the meaning of the 16th Amendment, ratified in 1913. It says that Congress has the power to “lay and collect taxes on income, from whatever source it may be derived.”

A few years later, the Supreme Court said that corporate actions held by taxpayers could not be taxed as income unless they were “made or received” as income. That decision was generally understood to mean that the government could impose taxes on salaries or stock dividends, but not necessarily on property or corporate wealth that grew in value. These are known as “unrealized gains.”

But many constitutionalists and tax experts had questioned that interpretation of the 16th Amendment. And in recent decades, Congress has taxed people who earn corporate income and own stock in some corporations, even if dividends are not paid each year.

Charles and Kathleen Moore's case began when they received a $14,729 tax bill for their ownership shares in an India-based company.

The Moores, who are retired and live in Washington state, said they received no income or dividends from their investment in the company, which supplies equipment to small farmers. They sued, claiming the tax was unconstitutional under the 16th Amendment.

But a federal judge and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed with them and upheld part of the 2017 tax bill passed by the Republican-controlled Congress and signed by President Trump. He imposed a one-time tax on Americans who owned shares in foreign corporations that gained value. The tax measure included big tax breaks for the wealthy, but to offset those tax revenue losses, lawmakers tried to claw back some gains Americans made overseas.

Backed by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and other business groups, the Moores petitioned the court with the help of Washington attorney David B. Rivkin and urged the justices to eliminate the foreign income tax.

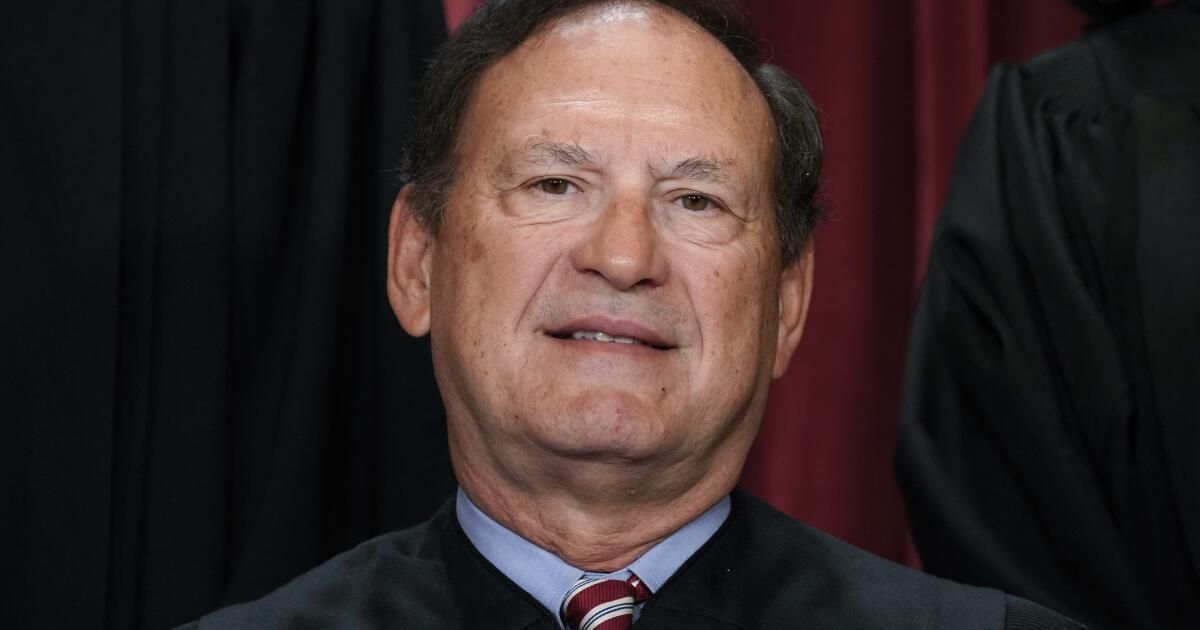

Some had asked Judge Samuel A. Alito Jr. to recuse himself from the matter.

Washington lawyer David B. Rivkin, who helped draft the appeal petition, interviewed Alito for two articles that appeared in the Wall Street Journal last year.

“There was no valid reason for my recusal in this case,” Alito wrote in response in September. “When Mr. Rivkin participated in interviews and co-authored articles, he did so as a journalist, not as an advocate. The case he is involved in was never mentioned; nor did we discuss any issue in that case either directly or indirectly.”

Alito agreed with Thursday's result. Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil M. Gorsuch dissented.

Thomas wrote the 16th Amendment says that income is “only income earned by the taxpayer. The text and history of the amendment make clear that it requires a distinction between “income” and the “source” from which that income is “derived.” And the only way to establish that distinction is through a performance requirement.”