The alarms are loud and clear.

Federal and international climate officials recently confirmed that 2023 was the hottest year on record on the planet – and that 2024 may be even hotter.

With a global average temperature of 58.96 degrees, Earth in 2023 was within striking distance of a dangerous limit: 2.7 degrees of warming during the pre-industrial period, or 1.5 degrees Celsius, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service. the European Union.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

The reference point is significant. In 2015, the United States was among 195 countries that signed the Historic Paris Agreementan international treaty drafted in response to the growing threat of climate change.

The parties agreed to keep global temperature rise to a maximum of 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels (and preferably below 1.5 degrees Celsius) to reduce the worst effects of climate change.

The preindustrial period refers to an era before humans began significantly altering the planet's climate through fossil fuels and other heat-trapping emissions. Most agencies measure this using temperature data between 1850 and 1900.

But latent temperatures from last year make it clear that the 1.5 degrees Celsius benchmark is moving away.

An A380 jumbo jet disappears into the clouds after taking off from LAX in December.

(Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times)

“At this point, it's really difficult to see a path to keeping warming below 1.5 degrees,” said Kristina Dahl, senior climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

To achieve this, he said, a reduction of more than 40% in global greenhouse gas emissions would be necessary by 2030.

“That requires a pace of emissions reductions that is really inconsistent with what we see on the planet to date,” Dahl said. “At the same time, it's very important that we continue to strive toward that goal, even if we know we won't.”

Crucially, the limit set in the Paris agreement does not refer to a single day, month or even year of warming, Dahl said. Rather, it refers to sustained warming over two or three decades. (The agreement does not specify a deadline and has been interpreted differently by different scientists.)

“Remember, exceeding this threshold, as defined in the Paris Agreement, is supposed to reflect when human-caused global warming consistently exceeds 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to preindustrial times,” the National Oceanic and Oceanic Administration wrote. Atmospheric in a recent report.

NOAA noted that global surface temperatures may be influenced not only by human-caused climate change, but also by natural climatic factors such as El Niño and random weather, which can briefly push monthly or even annual temperatures above the 1.5 degree Celsius threshold.

“To know when the Earth has passed that threshold, we have to look at longer time scales,” the agency said.

What is clear, however, is that each additional degree (or even a tenth of a degree) of warming will have impacts beyond those already occurring, including increased tree mortality, biodiversity loss, worsening wildfires, longer heat waves, extreme rainfall and major flooding.

In 2018, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published a Special report on the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold which outlined a series of potential futures based on different levels of emissions reductions and subsequent warming.

In an intermediate scenario, delaying action on emissions would lead the planet to experience a warmer decade in the 2020s before peaking at 2 degrees Celsius of warming by mid-century. Warming then begins to slow due to improving global efforts and technology.

In that world, deadly heat waves would hit major cities like Chicago, while droughts would hit southern Europe, southern Africa and the Amazon, the IPCC report says. The destruction of key ecosystems, including coral reefs, rainforests, mangroves and seagrass beds, would lead to reduced levels of coastal defense against storms, winds and waves, with Asia and elsewhere experiencing major flooding. .

The bleached tips of this staghorn coral show signs of distress from the warm water temperatures in the Florida Keys.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

That scenario also predicts that continued rising sea levels, increasing water scarcity and declining crop yields would put pressure on global food prices and lead to prolonged famines in some African countries. The world would also see increasing levels of public unrest and political destabilization, the report says.

These possibilities illuminate the need for urgent action, as well as the consequences of a half-degree Celsius increase from 1.5 to 2 degrees of warming. For example, about 75% of the world's coral reefs are expected to be lost with 1.5 degrees of warming, compared to 99% with 2 degrees, Dahl said.

The Antarctic ice sheets are also sensitive to that half a degree and would experience exponential melting at 1.5 degrees Celsius and above. Its melting would be “a tipping point in Earth's climate system that would be really difficult to recover from,” Dahl said.

Other differences include millions of additional people exposed to sea level rise, heat waves and water stress, according to a separate report from UK-based Carbon Brief groupwhich compiled data from dozens of studies.

With a warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius, the planet would soon see a rise of about 19 inches in sea level, a 16% increase in hot days, and an 8% decrease in Northern Hemisphere snow cover, says the report. But at 2 degrees Celsius, those numbers would increase to 22 inches of sea level rise, a 25% increase in hot days and an 11% decrease in snow cover, among other effects.

The current best estimate of when Earth will surpass the 1.5-degree benchmark is between now and 2040, according to the IPCC report. 6th climate change assessmentreleased last year.

However, the planet is not only approaching that limit, but It exceeded 2 degrees Celsius for the first time since records began. on two days in 2023: November 17 and 18, according to Copernicus.

Humanity has never before “had to face such a warm climate,” the agency's director, Carlo Buontempo, recently stated.

“There were simply no cities, no books, no agriculture, no domesticated animals on this planet the last time the temperature was this high,” Buontempo said. “This requires a fundamental rethinking of the way we assess our environmental risk, as our history is no longer a good indicator of the unprecedented climate we are already experiencing.”

In November, world leaders gathered in Dubai for COP28, the same annual climate conference where the Paris agreement was established in 2015. In Dubai, nearly 200 nations agreed for the first time move away from fossil fuels that heat the planet.

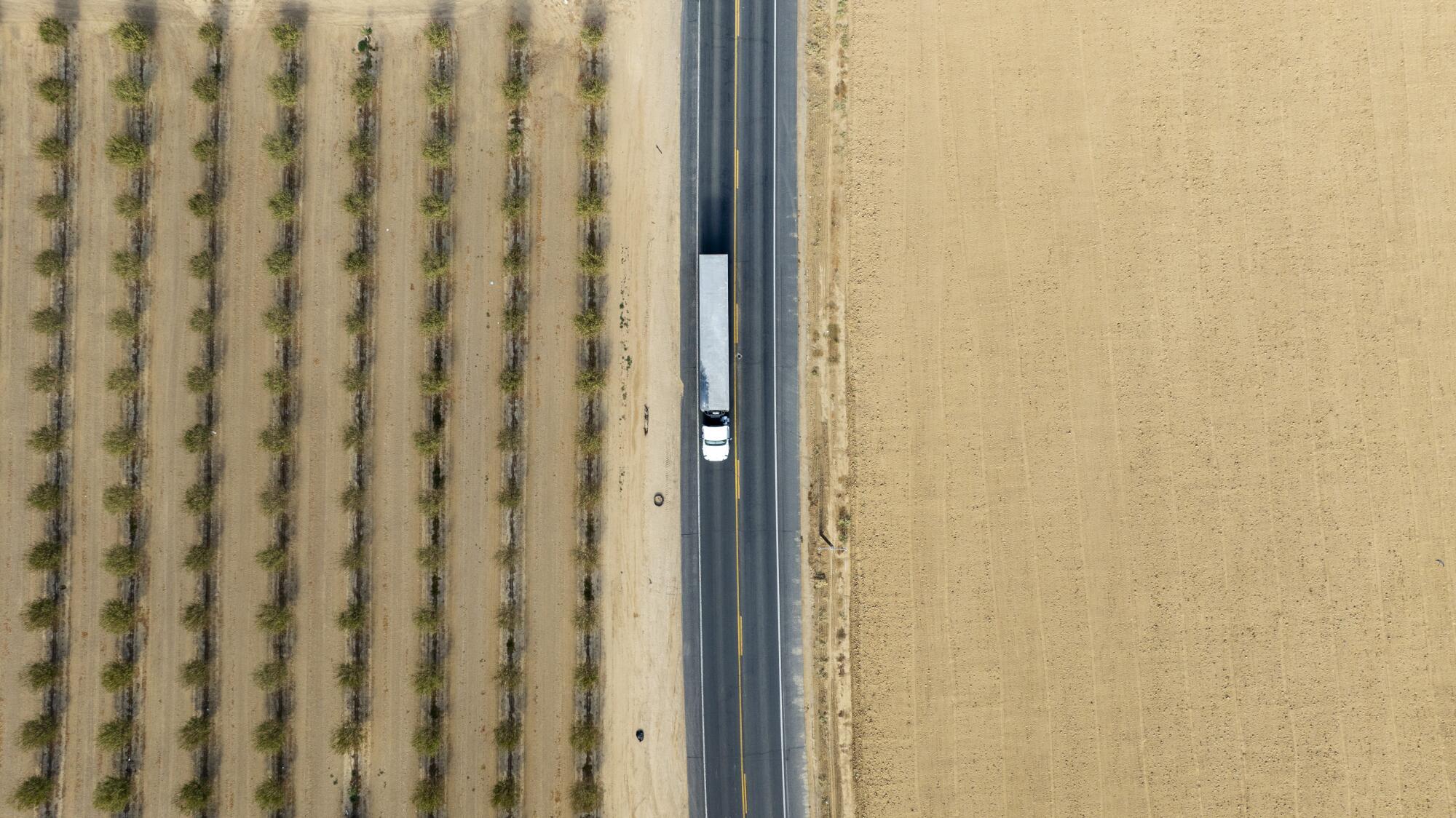

A tractor trailer passes an almond orchard in Buttonwillow in November.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

Dahl, of the Union of Concerned Scientists, said it's a step forward. What's more, he said, it doesn't necessarily matter where the emissions reductions come from. While every country should do its part, places that are lagging behind may be bolstered by places that are making deeper cuts, like California.

“If we as a country can acknowledge our culpability as historically the world's largest emitter and really take the lead in aggressively reducing emissions, that will have a significant impact,” Dahl said.

Limiting sustained warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius is still within reach, he added, as long as countries continue to strengthen and implement their pledges to reduce emissions.

“Every tenth of a degree really matters,” he said.

And although the 1.5 degree threshold is likely to be exceeded, it is important to continue working towards it. Dahl compared it to taking her children to school in the morning when they are already late, noting that it is better to be late by a minute than by an hour.

“That's how I think about the 1.5C target,” he said. “At this point, it would be incredibly difficult to achieve and we have to keep trying.”