She was one of Charles Manson's first disciples, a flower-grown orphan who spoke passionately about LSD and redwoods, and one day in 1975 she brought a loaded gun to see the president.

Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, 26, lived in a $100-a-month penthouse in an old Victorian house on P Street, just blocks from the state capitol in Sacramento. She had moved to the city to be near Manson, who had been imprisoned for a time in nearby Folsom for the Los Angeles home invasion murders that made him famous.

Fromme did not seem to harbor any specific animosity toward President Ford, but she represented an establishment that she and the Manson clan despised. She had been distributing apocalyptic press releases. That summer, speaking to the Associated Press, she promised a massacre while invoking two of Manson's crime scenes and a massacre in Vietnam.

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, from the momentous to the obscure, delving into the archives and memories of those who were there.

“If the Nixon reality — with a new Ford face — continues to rule the country against the law, our houses will be bloodier than the houses of Tate-LaBianca and My Lai combined,” he said.

Then, as now, the Secret Service had a long list of people who posed a potential threat to the president. Despite her menacing rhetoric, Fromme's name was not on the list.

She was waiting calmly near an orange tree in Capitol Park around 10 a.m. on Sept. 5, wearing a hand-stitched Little Red Riding Hood-style cape that was supposed to symbolize a new ascetic lifestyle of sacrifice and activism. On her leg, beneath her dress, was a makeshift holster holding a borrowed .45-caliber pistol that had been developed for the military.

After speaking to a group of business leaders over breakfast, Ford left the Senator Hotel and walked across the street to the park. He was headed to see Gov. Jerry Brown in his office, about 500 feet away. Hundreds of people had gathered to see him and shake his hand.

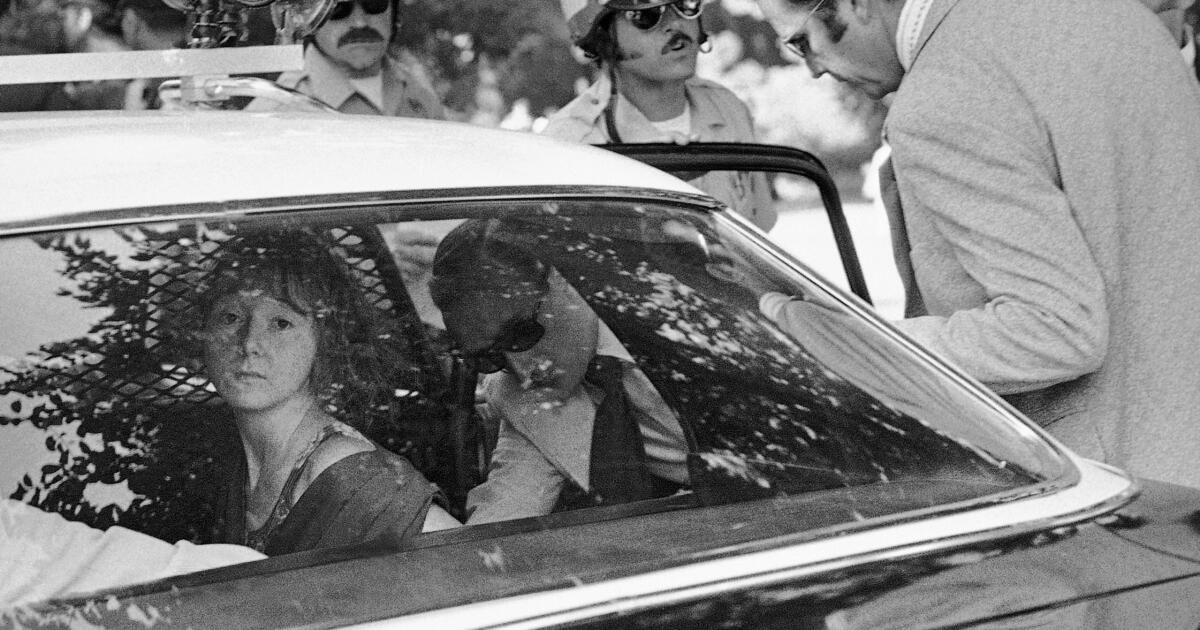

Secret Service agents handcuff Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme after she pointed a gun at President Ford during a visit to the state Capitol in 1975.

(Associated Press)

Karen Skelton, then 14, had skipped school to see the president. She remembers there were three or four people in the crowd, and Fromme was a few feet ahead of her, on the right.

“I thought she was a bit odd, because she was wearing a red robe,” Skelton told The Times in a recent interview. “At one point she looked around and looked up and said, ‘Oh, what a lovely day.’”

The president had opted not to travel to the Capitol in his armored vehicle, and Larry Buendorf, a 37-year-old Secret Service agent, was part of the security team accompanying him on foot.

“Instead of a motorcade, he said, ‘I think I’ll just walk,’” Buendorf recalled this month. “It wasn’t a planned thing, so we all scrambled to get things in place as best we could. A lot of people lined up along the sidewalk. He was just walking, shaking hands. I was right next to him, making sure no one held him too long and no one took his watch. My focus was on the hands reaching out to him.”

That's when she saw the .45-caliber pistol in Fromme's hand, pointed at the president. She stepped in front of Ford and grabbed the gun. Ford was taken to safety, and Fromme was thrown against a tree and handcuffed. Witnesses heard her exclaim, “He didn't shoot himself,” and “He's not a public official.”

Somehow, Buendorf cut his hand, but he's not sure exactly how.

Investigators did not find any bullets in the chamber of the gun, but they did find four in the magazine.

“If you pull the slide back, it loads a round. If I had already had one in the chamber, I don’t think I would have made it. I think it would have gone through me and the president,” Buendorf said.

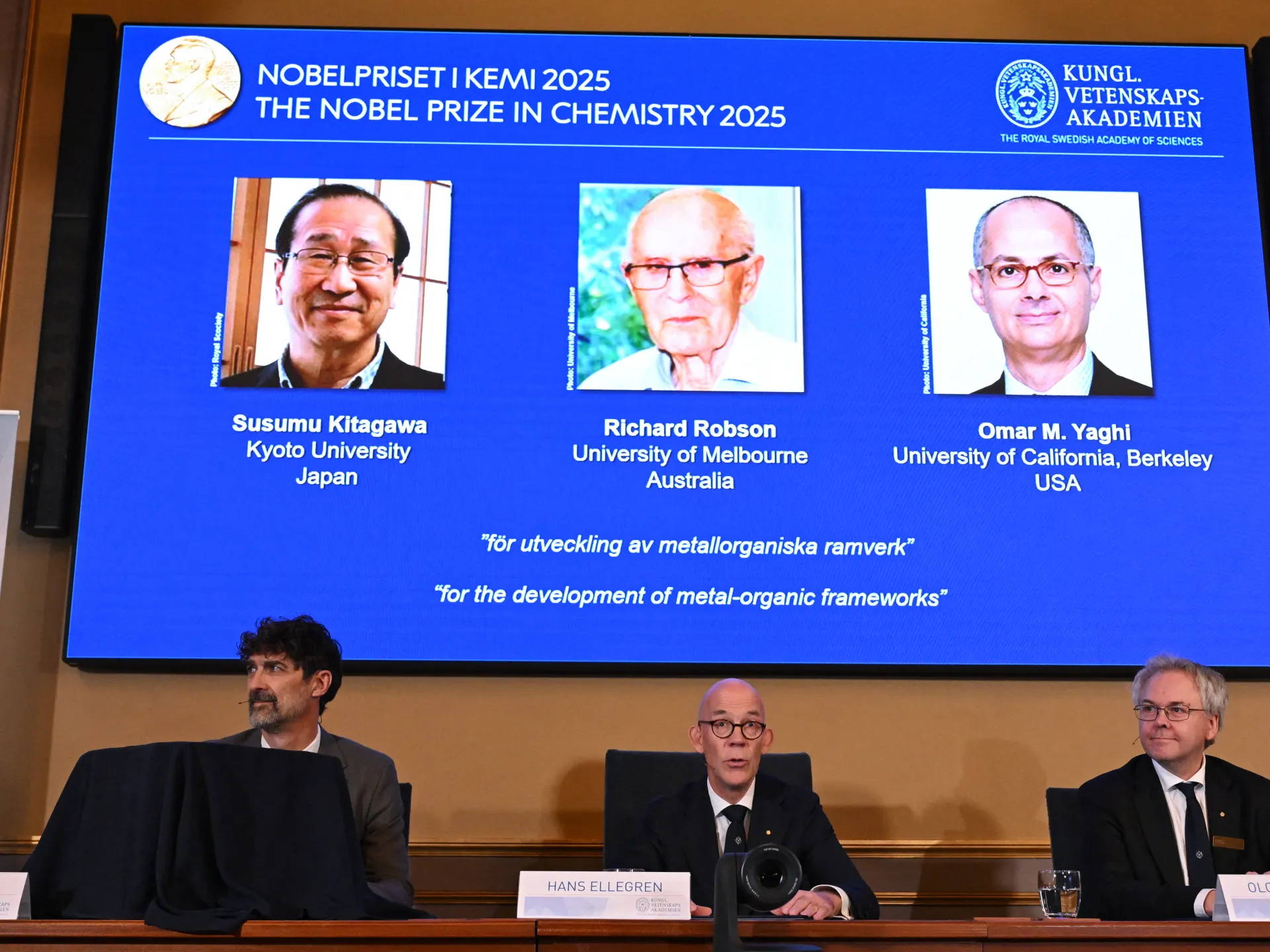

President Ford is rushed to safety after an assassination attempt outside the California State Capitol.

(Associated Press)

The reporters gathered at the apartment where Fromme had been living with another Manson disciple, Sandy Good, who warned of a group called the International Peoples' Retribution Tribunal, which, she said, would bring death to corporate and political leaders.

“A wave of killers, thousands of them, will move through the bedrooms with butcher knives,” he said. “These people who are killing our planet deserve to die.”

Investigators found no evidence of a broader conspiracy to kill Ford, nor any proof that the imprisoned Manson had given the order.

Still, Stephen Kay, a former Manson prosecutor, has long suspected that Manson egged her on as a way to gain more notoriety, perhaps by passing her information through an intermediary.

“There's no way Squeaky could have thought of that on her own,” he told The Times, describing her as a “space cadet.”

“Manson loved to be on the news himself or have his family on the news,” he added.

The daughter of an aeronautical engineer, Fromme was raised in an upper-middle-class home in Redondo Beach. She was kicked out of her home as a teenager and met Manson on Venice Beach in 1967. Manson called himself “the Gardener,” the caretaker of lost flower children. Of the forces that influenced her, Fromme wrote in her memoir “Reflexion”: “Charlie and LSD stand out.”

In “Helter Skelter,” his account of the Manson murders, prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi wrote that Fromme wore a perpetual smile, possessed a “little-girl quality” and seemed to radiate an “inner contentment” that reminded him of a religious fanatic. “Charlie is love” was her doctrine. At the Spahn Ranch near Chatsworth, Manson assigned Fromme to care for the blind, elderly owner, who allowed the Manson clan to stay on his property and, according to Bugliosi’s account, enjoyed the sexual attentions of female disciples.

As leader of the family in Manson's absence, she helped embroider an elaborate ceremonial vest for him, weaving in her own red locks. In the 1973 documentary “Manson,” Fromme posed with rifles and daggers, declared Manson to be God and said she was willing to die for him.

“Anyone can kill anyone,” he said.

Undated photograph of the Spahn Ranch.

(UPI)

Manson did not order Fromme to accompany the gang of killers responsible for the murders of Tate and LaBianca in August 1969, but during his trial, she held vigil outside the Hall of Justice in downtown Los Angeles and carved an X into her forehead in solidarity.

“After the trial, I was walking out to the parking lot and Squeaky and Sandy sneaked up on me and told me they were going to do the same thing at my house that they did at Tate’s house,” said Kay, the former prosecutor. “And we all know what they did at Tate’s house.”

When Fromme was arraigned on charges of attempted murder of Ford, she demanded that the federal judge stop the logging.

“The important thing is the redwoods,” Fromme said. “We want to save them. Do you understand that this is like cutting off your arms and legs?” She added: “The gun is pointed and it’s up to you to fire it.”

At trial, he asked that Manson be brought to testify in court, but the judge refused. At one point, he threw an apple at a prosecutor. In an attempt to prove that he never intended to fire the .45, the defense showed that he had taken shooting lessons at a shooting range and knew how to handle firearms.

“The government was very concerned about the possibility of an assault conviction rather than an attempted murder conviction because there was evidence that she was very familiar with guns,” said journalist Jess Bravin, author of “Squeaky: The Life and Times of Lynette Alice Fromme.”

She was convicted of trying to kill Ford and given a life sentence. In 1987, after hearing a rumor that Manson was dying of cancer, she escaped from a minimum-security federal prison in West Virginia, hoping, she said, to be near him. She was captured two miles away. In 2009, at age 60, she was released on parole.

Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme waves to the camera as she arrives at the federal courthouse in Sacramento in 1975.

(Associated Press)

Bravin said that when he interviewed Fromme, who maintained a kind of religious devotion to Manson until her death, she told him she had gone to the park that day unsure of what she would do.

“She had no personal feelings about [Ford] “One way or another,” Bravin said. “She was very angry at the system and what she felt was environmental degradation. Ford was coming to talk to businessmen in Sacramento. She felt like it was destroying the redwoods.”