Geophysicist John Vidale noticed something surprising while tracking how seismic waves move from the Earth's crust through its core.

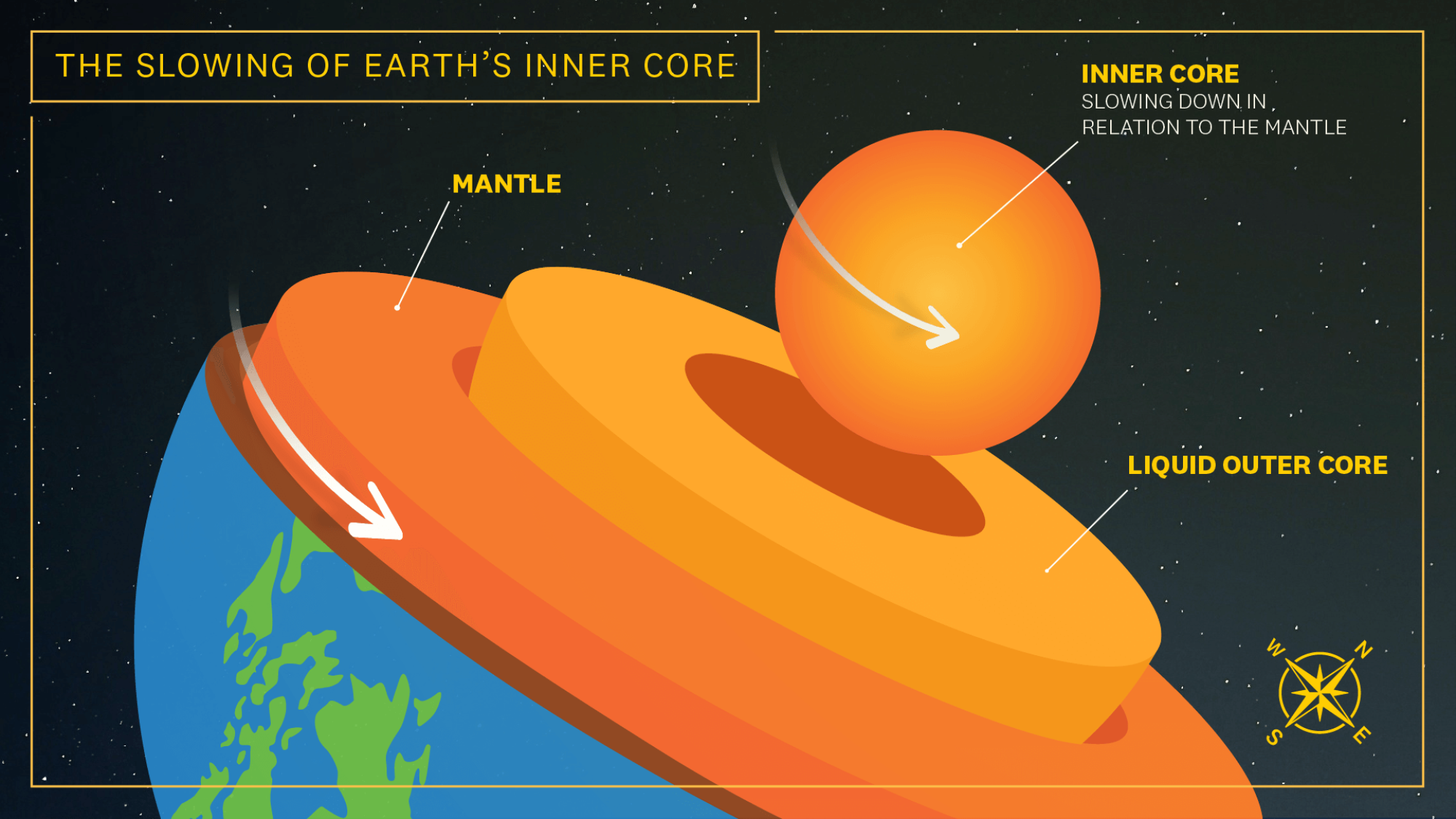

The very center of the planet, a solid ball of iron and nickel floating in a sea of molten rock, appears to be slowing relative to the Earth's motion. The inner core has slowed so much that it has practically gone into reverse.

The fluctuations occurring 3,000 miles underground won't affect life on the planet's surface in any noticeable way, at least not for now, said USC geophysicist John Vidale.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

The discovery by Vidale and his colleague Wei Wang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, published recently in the journal Nature, offers the most compelling evidence yet that the nucleus appears to operate with a mind of its own.

“He might go back and forth, but he might also just walk randomly,” Vidale said. “He went one way for a while, then went back in the opposite direction. Who knows what he’ll do next?”

The fluctuations occurring 3,000 miles below us won't affect life on the planet's surface in any noticeable way, at least not for now, Vidale said.

“From what we’ve seen, it has essentially no effect on people,” said Vidale, dean of sciences and earth sciences professor at USC’s Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “It’s part of the basic understanding of the evolution of the planet. What we’d also like to know in more detail is what are the forces that drive the inner core.”

Scientists first had an inkling that the inner core was moving in the 1990s, he said. It has taken years to back up that theory with hard evidence, largely because of the difficulty of studying a mass so far out of reach and suspended within a hellish sea of liquid iron at 8,000 to 10,000 degrees.

Instead, Vidale, who was director of the Southern California Earthquake Center at USC from 2017 to 2018, peered into the planet’s interior by tracking seismic waves from earthquakes that occurred off the lower tip of South America. As the waves passed through the heart of the planet, they were recorded by 400 seismometers located at the other end of the globe, in Alaska and northern Canada. The sensors were the same kind used to measure ground vibrations during nuclear testing.

He compared those refined readings to seismic signals recorded in previous years to see if they matched up. That's how he determined that the rotation has been slowing since 2010. Before that, the core's spin had been speeding up.

The findings add to the mystery of the most inscrutable part of our world, Vidale said. Literature and lore involving the Earth's core have filled the knowledge gap with all sorts of outlandish ideas.

“I’m not a philosopher, but we’ve all had nightmares about what’s going on on the planet,” Vidale said. “Just a couple hundred years ago, people thought the planet was hollow and there were people living there. It’s pretty exotic — exotic like Jupiter, but it’s right under our feet.”

In Jules Verne’s 1864 science fiction classic “Journey to the Center of the Earth,” a German professor, his nephew, and their guide descend to the planet through a volcano in Iceland; along the way they encounter caverns, an underground ocean, living dinosaurs, strange sea creatures, and even a prehistoric giant herding mastodons; and are eventually spewed out through a volcano off the coast of Sicily.

The 2003 disaster film “The Core” imagines that the Earth’s core has stalled, damaging the magnetic field surrounding the planet and triggering a violent electrical storm that destroys Rome and “invisible microwaves” that melt the Golden Gate Bridge. A team of expert scientists digs into the Earth’s layers to reactivate the core with a nuclear bomb.

In the real world, no human could survive the unimaginable heat and crushing pressure, even if a vehicle capable of tunneling to the core existed, Vidale said.

It's true that the outer core generates electrical currents that sustain the planet's magnetic field, but Vidale says changes in the Texas-sized inner core are too minuscule to have an impact.

Although the planet's subterranean reality is less fantastical than novels and Hollywood movies portray it, it remains fascinating to those like Vidale, whose job it is to counter conjecture with facts.

What is increasingly clear is that the inner core is susceptible in different ways to the activity of the Earth's surrounding layers.

“The mechanics are that the outer core is circulating and creating a magnetic field, and therefore it kind of pushes the inner core back and forth,” Vidale said.

Recent discoveries about the inner core have sparked strong disagreements among the world's leading Earth scientists, says USC's John Vidale. Some don't believe the core rotates at all.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

Another player in the endless tug-of-war taking place inside the planet is the lower level of the planet's mantle, whose mix of hard, less dense matter produces its own peculiar magnetic attraction, Vidale said.

“We think the outer core is shaking the inner core, but the mantle is trying to keep it aligned, so that’s probably why it’s wobbling,” he said.

Recent discoveries about the inner core have fueled sharp disagreements among the world's leading Earth scientists and given rise to competing theories of varying credibility, Vidale says. Some don't believe the core spins at all. Others insist that forces on the surface, such as earthquakes, briefly disrupt the rotation.

Over the phone, Vidale reads a review by an Australian scientist who has greeted Vidale’s recent findings with much skepticism. The Australian proclaims that the analysis will lead to “the erosion of seismology as a credible branch of science and the destruction of seismologists as credible researchers.”

“I think he's just frustrated; he knows he's lost,” Vidale said, joking gently with his teammate.

“It's exciting because the core is quite large, it moves in measurable amounts, and it's a mystery,” Vidale said. “We're making progress and seeing more things, discussing with people around the world and trying to get more data… What our paper has done is convince most of the community.”