The campaign to be Donald Trump’s running mate has played out in an unusually public manner, including a parade of potential vice presidents who attended the New York trial that led to his historic criminal conviction. Though Trump has suggested he might not name a running mate until this month’s Republican convention, there has been no shortage of opinion readings from journalists and pundits: Which candidate got a bad reception from conservative media? Who shared a meal with the former first family? Who defended Trump most vigorously against the despised judge or prosecutor of the day?

Many commentators may not be so interested in which of the vice presidential candidates would be the better candidate, but that is the question that interests us most and the most important one for the country.

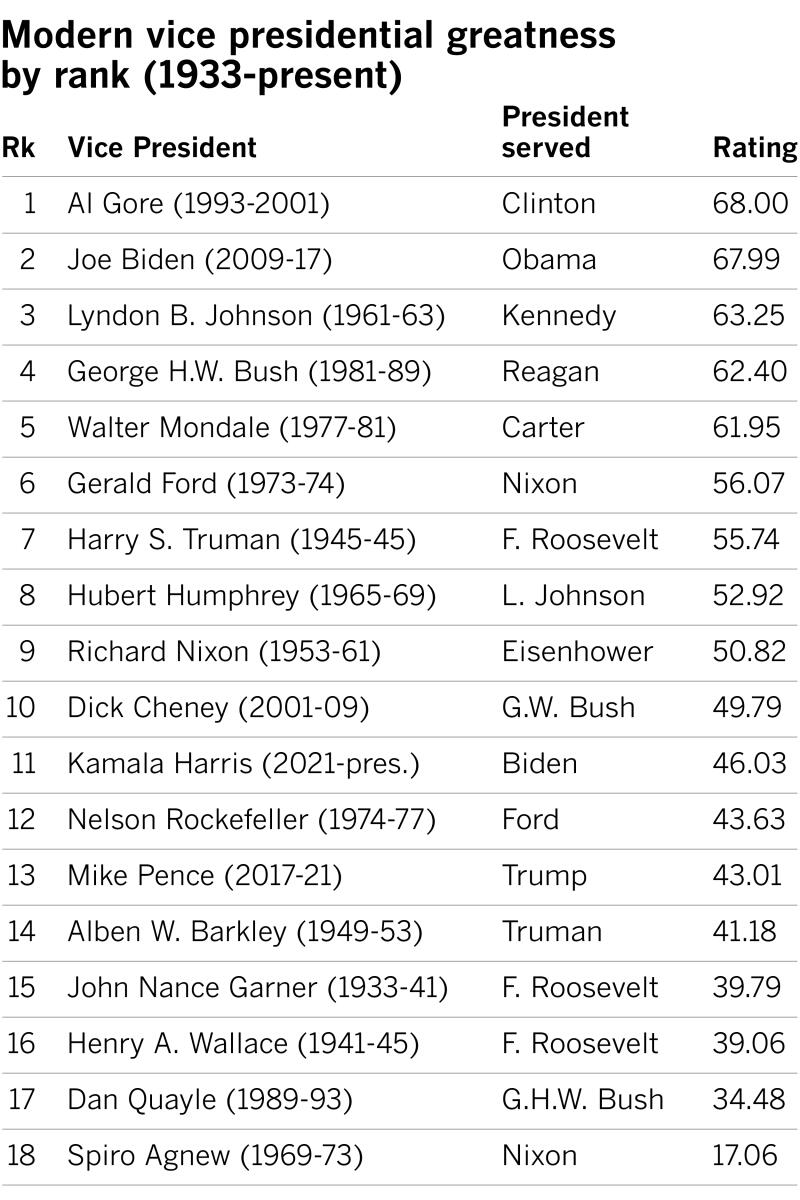

That's why when we made our most recent Presidential Greatness Project In a survey of academics, we asked experts to rate vice presidents and presidents. The resulting rankings, which ranged from John Nance “Cactus Jack” Garner, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first vice president, to Kamala Harris, are intriguing.

Al Gore topped the list as the best modern vice president, closely followed by Joe Biden, who also recently entered the presidential rankings in the upper thirdLyndon B. Johnson (Kennedy), George HW Bush (Reagan) and Walter Mondale (Carter) rounded out the rest of the top five.

Nixon's vice president, Spiro Agnew—who resigned after a bribery scandal—came in last place, followed by Dan Quayle (George HW Bush), Henry Wallace (FDR), Garner and Alben Barkley (Truman) for the last five spots.

Harris and Mike Pence — who served under the last president on the list, Trump — ranked in the bottom half of the list of vice presidents, at 11 and 13 out of 18, respectively. The low rankings for the current vice president and her predecessor reflect the view among experts that they were not particularly active partners in their administrations.

This is a departure from the old conventional wisdom about the role of vice presidents, which was that they served as a marginal electoral asset (for example, by representing a key state or congressional district) and essentially kept the pulse on the ball. Historically, vice presidents were like offensive linemen in American football: If their names were in the news, it probably wasn’t good.

Top to bottom, left to right: Vice Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson, Harry S. Truman, Dan Quayle, Gerald Ford, Al Gore, Kamala Harris, Mike Pence, Spiro Agnew, Joe Biden, George H.W. Bush, Dick Cheney, John Nance Garner.

But the vice presidency has taken on a dramatic importance in recent decades. Garner’s infamous comparison of the office to a bucket of lukewarm “spit” (to put it delicately) may have been accurate when he served under FDR, but modern vice presidents can be partners with presidents in policymaking. Today, successful vice presidents provide advice, work with Congress, and deliver the president’s message.

Beyond the overall rankings, we were able to evaluate our most recent vice presidents (since Mondale) on several dimensions of the contemporary vice presidency. These dimensions further underscore the policy partner component of the institution.

For example, in addition to being considered the best modern vice president, Gore led the field as a policy adviser, reflecting projects like his “reinventing government” initiative to cut bureaucracy and make government less expensive and more efficient. Biden scored highly in congressional relations, largely because of his “big… matter” role in helping to pass the Affordable Care Act into law. Dick Cheney, who did not receive a high rating overall, was nonetheless seen as an important policy adviser to President George W. Bush.

The best vice president ever? Joe Biden and Al Gore (the former pictured here presenting the latter with the Presidential Medal of Freedom) both ranked high in a panel of experts' evaluation of our country's last 18 vice presidents.

(Alex Brandon/Associated Press)

When we asked our respondents to give us their own definitions of vice presidential greatness, we received a wide range of responses, but several concepts and themes were consistently repeated. The words that appeared most frequently in these definitions were “policy,” “effectiveness,” “support,” “position,” and “agenda”—all of which typically relate to White House politics rather than electoral politics.

This is consistent with responses to another question we asked about the most important characteristics in a vice president. Respondents indicated that the ability to act as a policy advisor or presidential representative was far more important than a conventional focus on electoral politics.

Many of the potential running mates Trump is considering have at least the experience needed to become successful vice presidents. Governors such as Ron DeSantis of Florida and Doug Burgum of North Dakota have executive experience, as does Kristi Noem of South Dakota, who appears to be in free fall, and Trump’s primary-season nemesis, former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley. Sens. Tim Scott of South Carolina, J.D. Vance of Ohio or Marco Rubio of Florida could serve as a bridge to Congress. Any of them could have the makings of an effective political partner in the White House if given the opportunity and inclination — no sure thing considering the fate of Pence’s vice presidency.

That's a shame, because this year it's especially important to have a running mate who can provide stability and perform competently. Given the advanced age of both candidates, as well as the possibility that Trump's legal problems will haunt him in a second term, there's a higher than usual chance that either candidate will become president.

There is no Mount Rushmore for vice presidents, but if there were, our poll of experts suggests it would be determined by productive governing partnerships, rather than a balance of political candidates. In a year of widespread public dissatisfaction with the presidential candidates and a clear awareness of their shortcomings, many voters might well look for that potential in the running mates.

Justin Vaughn is an associate professor of political science at Coastal Carolina University. Brandon Rottinghaus is a professor of political science at the University of Houston.