This week's televised debate between Slovakia's nine presidential candidates often seemed as if it were taking place in Moscow.

“As president, I want to get Slovakia out of the dungeon of nations that is the European Union,” said Milan Nahlik, a police officer who ran unsuccessfully for parliament four years ago.

“As president, I would vote in favor of lifting sanctions against Russia, because they are contrary to international law,” said Stefan Harabin, a former Supreme Court judge and third most popular candidate, echoing Russian arguments that sanctions should be approved by the government. UN Security Council.

“Mr Harabin, you are directly responsible for the extensive and forceful way in which we handed over our national sovereignty to Brussels. And today you act as if you had nothing to do with it,” replied Marian Kotleba, the neo-Nazi candidate who is trailing in the polls.

He was referring to Harabin's long-standing support for the Lisbon Treaty, which empowered the European Union to sign international treaties on behalf of its members, but fell short of a higher aspiration: introducing majority voting in defense and foreign affairs, thus preserving the power of the member states. to veto decisions.

The loss of national sovereignty in foreign relations was a fear that the leading candidate and former Prime Minister Peter Pellegrini also exploited.

“Pellegrini brought out a carefully prepared insidious lie and a story about how Germany and France will order that Slovakia must “gather our fully armed soldiers at the train station” to deploy them to Ukraine and “no one will ask us,” wrote journalist Tomas Bella. in the independent newspaper Dennik N.

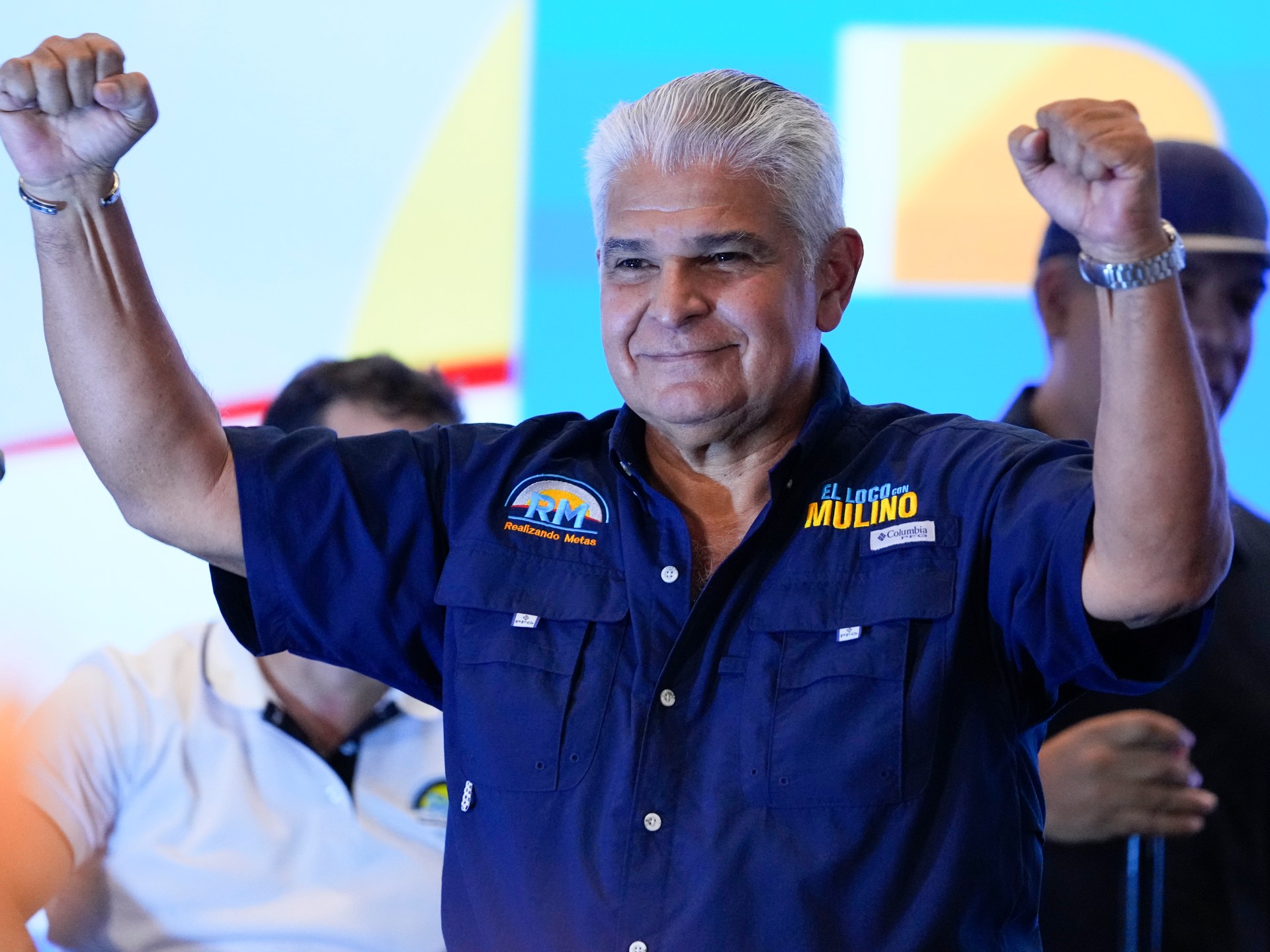

Pellegrini, who leads the Hlas party, a splinter group from Prime Minister Robert Fico's ruling Smer party and now in coalition with him, has presented himself as the pro-peace candidate, repeating Pope Francis' recent controversial statement: “We must find the courage to raise the white flag.”

In Slovakia, the role of the president is largely ceremonial.

However, as the official commander-in-chief of the armed forces, the president can declare war and mobilize, declare martial law, and return a law for Parliament to reconsider. He can also appoint and recall judges, including Supreme Court justices, demand government reports on specific areas, or call a referendum on a policy issue.

Is there a candidate more aligned with Ukraine and its Western allies?

The only pro-Western voice in the field and the only candidate supporting Ukraine's fight against the Russian invasion was that of former Foreign Minister Ivan Korcok, who is running a close second to Pellegrini in opinion polls.

“Peace in Ukraine can be tomorrow, and it will be when the Kremlin regime led by President Putin stops killing innocents and destroying the entire country. Peace cannot be a capitulation,” Korcok said.

Korcok also agrees with Ukraine that Russia should return the five regions it has invaded since 2014.

“I don't think Ukraine should give up part of its territory to achieve peace,” he recently told the AFP news agency.

How are Slovaks likely to vote?

Despite the crowded pro-Russia field, the Slovaks seem quite divided between Korcok and everyone else.

A poll last November suggested that 60 percent of respondents would vote for Pellegrini, compared to 41 percent for Korcok. But in a January poll, Pellegrini's lead narrowed to within the margin of error: 40 percent to 38 percent.

A March 18 poll put them even closer, with Pellegrini leading by just one point, at 35 percent.

“It is unlikely that anyone will obtain more than 50 percent of the valid votes needed to be elected in the first round, something that has never happened in almost 25 years of direct presidential elections,” Michaela Terenzani wrote in The Slovak Spectator.

If he is right, a second round between the two main candidates (probably Pellegrini and Korcok) will take place on April 6.

Does Slovakia officially support Ukraine?

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion two years ago, Slovakia became an ardent supporter and contributor of arms to Ukraine, its eastern neighbor.

In addition to ammunition, it sent self-propelled artillery, an S-300 air defense system, transport helicopters and MiG fighter jets. Slovakia quickly received additional NATO battlegroup and Patriot air defenses for its own security.

Its liberal president, Zuzana Caputova, was one of the first Western leaders to support Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in kyiv, three months after the invasion.

According to a Eurobarometer survey at the time, 80 percent of Slovaks felt sympathy for Ukrainians.

So how was Slovakia divided in half?

“There are many channels of misinformation. There are so many paid agents, propagandists, that Slovakia is contaminated with fake news,” Dennik N journalist and activist Michal Hvorecky told Al Jazeera.

“Most of these fake news have to do with the Russian war in Ukraine, the situation in Donbass, Ukrainian democracy, especially hatred towards the West,” Hvorecky said.

When communism collapsed in Europe, Slovakia rushed headlong into the EU and NATO, along with the rest of its former Soviet neighbors, becoming a member of both organizations in 2004. Russia invaded Ukraine to pursue those same options.

Why would half of Slovaks now deny Ukrainians that option?

“In 1968 we were occupied by half a million Soviet soldiers. Now, 50 percent of Slovaks will say that we are neither part of the West nor the East, we are somewhere in between,” Hvorecky said.

“Somehow we tend to forget that many people feel like losers from the transformation. Long after this forgotten past 30 or 40 years ago, they will tell you that there was more stability, there was more security,” she said.

The illiberal Prime Minister Fico and former judge Harabin belong to that generation of former communists, and the Smer and Hlas parties were largely built on Soviet-era political talent.

The younger generation feels very differently.

A mock election at 180 high schools across the country showed this week that people too young to vote on Saturday would choose Korcok in the first round with 57 percent of the vote.

Pellegrini and Harabin would get 15 and 10 percent, respectively.

In addition to sympathy for the Kremlin narrative and generational longing for the past, Slovakia suffered economically from the Ukrainian war.

It is one of the few landlocked Eastern European states, along with Austria, Hungary and the Czech Republic, that could not easily replace Russian oil when the EU banned it in December 2022.

Slovak support for energy sanctions against Russia was among the lowest in the EU.

What is at stake for Slovakia and Europe?

Caputova entered politics through environmental activism and campaigned to abolish coal. She supports Ukraine, free media, LGBTQ rights, gender equality, and women's right to choose abortion.

In almost every respect, he has defended what Fico's tripartite coalition, formed last December, abhors.

Fico stopped all military shipments to Ukraine days after winning the October parliamentary elections.

Its Minister of the Environment, Tomás Taraba, denies climate change.

Its Minister of Culture and Media, Martina Simkovicova, owns an online television station that amplifies Russian messages about Ukraine.

His Defense Minister, Robert Kalinak, has been accused along with Fico of allegedly using tax records to wage smear campaigns against political rivals. His Foreign Minister, Juraj Blanar, broke with the EU policy of excluding Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and met him last Saturday.

Observers believe a Korcok victory would at least preserve a liberal voice.

“As president you don't have executive power but people can listen to you. Your voice can be very loud. You can speak in parliament, you can speak on national television. “It is a very respected position,” Hvorecky said.

That's partly what motivated him to revive anti-Fico protests in Bratislava last October, and the response has given him hope.

“Throughout the winter, November, December and until March, people were protesting almost every week under the frost, the snow, the wind, the rain, every Thursday there were massive demonstrations,” he said.

He fears a return to the days of the previous Fico government, when investigative journalist Jan Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kusnirova, were murdered while investigating tax breaks for oligarchs. Mass protests that followed the February 2018 killings forced Fico to resign.

What would a Pellegrini victory mean for Slovakia under Fico?

Although nominally head of a separate party, Pellegrini is close to Fico. He replaced Fico as prime minister after Fico resigned. Smer participated in the 2020 parliamentary elections with Pellegrini leading the vote.

“When Pellegrini is president, Fico's path to power will no longer be blocked by any balance. There will be no balance of power,” Hvorecky said.

“Pellegrini presents himself as an independent political personality, but acts mainly as Fico's subject… Korcok does not have Fico on his head or on his shoulders all the time. He is free and says what he thinks,” wrote journalist Matus Kostolny in Dennik N.

Even if Pellegrini wins, Fico's progress may not be easy.

Slovakia, Hungary and Poland once formed an illiberal bloc, pursuing similar plans to strangle opposition media and control judicial appointments.

Last year, Poland abandoned that group when it brought to power a center-left coalition under Donald Tusk.

Hungary's opposition to Ukraine's EU candidacy and greater financial aid were set aside at the European Council last December and February.

Above all, none of the illiberal candidates have seriously contemplated leaving the EU or NATO. That suggests that the growing threat from Russia is making these bodies increasingly important and foreign and defense policy sovereignty increasingly irrelevant.