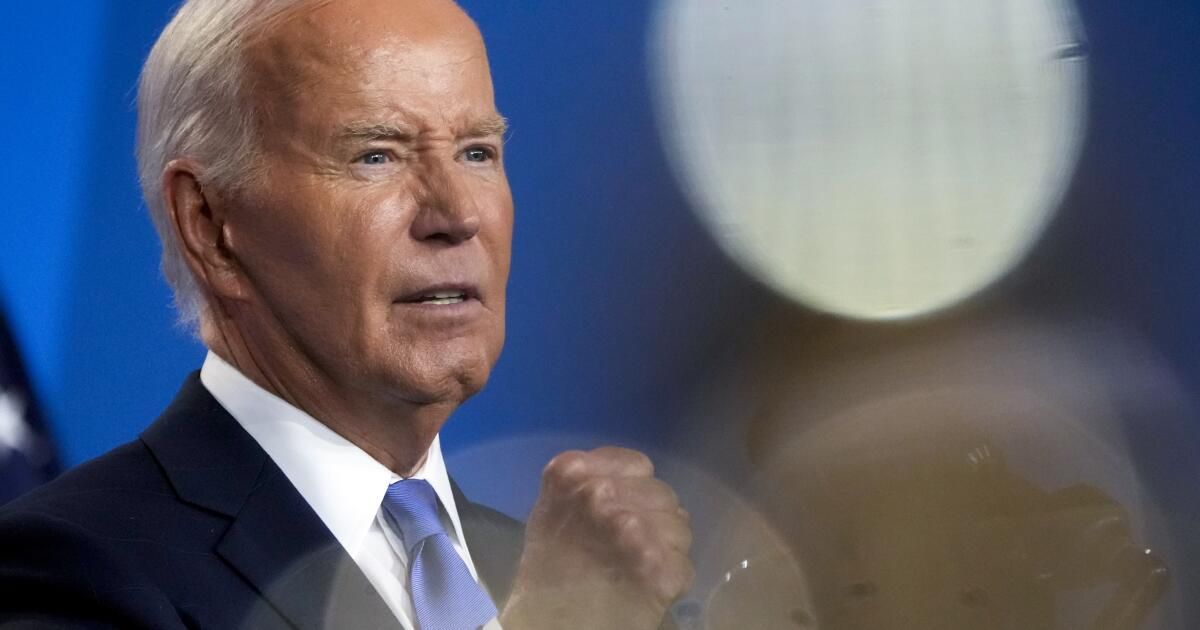

News from Milwaukee and the Republican National Convention has dominated this week, but it hasn’t stopped speculation about whether Joe Biden will or should withdraw as the Democratic presidential nominee. Many Democrats who want change are eager to have an open race, so the wild hoopla at the Democratic convention in Chicago in August can begin.

The hope that an open convention is the path to victory is a pipe dream.

For many members of Congress and others with political insight, an open nominating convention in Chicago in four weeks is the best way to secure an ideal nomination (Whitmer-Warnock seems to be the most talked about). At the very least, they want to have a contest, an open process that results in a nominee. For some, if Kamala Harris prevails in that context, directly defeating other rivals, it would bolster her candidacy. And the enthusiasm of an open convention would give the Democratic ticket the boost it needs.

A little history is in order. The last time there was a convention with more than one ballot was in 1952. Both parties held some primaries that year, but they were basically beauty contests in which no candidates were chosen. The Democratic candidate, Adlai Stevenson, did not even participate in a primary; at the convention (in Chicago, by the way), he was selected and won on the third ballot. The Republican candidate, Dwight Eisenhower, split the primary victories with his main rival, Robert Taft, but those results had little to do with his ultimate nomination.

Although in all subsequent conventions the nomination was decided on the first ballot, there have been many that might be called open and contested conventions, where candidates jostled and malcontents were determined to make their discontent known.

For Republicans, one need only think of the 1964 convention at San Francisco’s Cow Palace. Barry Goldwater emerged victorious in the first round after his recently divorced and remarried rival Nelson Rockefeller failed, but not before moderate Republicans led a last-ditch effort in support of Pennsylvania Governor Bill Scranton to wrest the nomination from him. The bitterness on the convention floor, including Rockefeller’s near-booing from the podium, left the party divided. Goldwater would probably have lost in any case, but his defeat by Lyndon Johnson was broader and deeper as a result of the fractures on display at the convention.

Then came 1976. At Kemper Stadium in Kansas City, Missouri, the Republican nomination was in serious jeopardy as the convention began. Incumbent President Gerald Ford, who did not have a majority of delegates, faced a stiff challenge from Ronald Reagan. Ford managed a narrow first-round victory, but a large number of disaffected conservatives threatened to leave the Republican Party and form a new party, contributing to Ford's narrow defeat at the hands of Jimmy Carter.

For Democrats, of course, the Chicago meeting in August could be a fresh experience of déjà vu. Their 1968 meeting is the ultimate example of a bitterly contested convention, in which incumbent Johnson’s withdrawal, prompted by a challenge from Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy, led to a fight between Robert F. Kennedy and Vice President Hubert Humphrey that was upended by Kennedy’s assassination in June. Most of Kennedy’s delegates went to Humphrey, who won the nomination handily on the first ballot. But anti-Vietnam War demonstrations outside the convention hall were met with tear gas and violence by Chicago police, and after Connecticut Senator Abe Ribicoff used the podium to denounce Mayor Richard J. Daley’s “Gestapo tactics,” the vivid image inside the hall was Daley shaking his fist and shouting an anti-Semitic epithet at Ribicoff. All of this left Humphrey with the opposite of a “convention coup.” In November, he fell short, a defeat easily attributed to the chaos at the convention.

In 1980, the Democrats faced off again in New York City. Carter, the incumbent, easily prevailed and won the nomination, but only after a stiff challenge from Massachusetts Senator Edward M. Kennedy. Kennedy’s defiant convention speech was by no means a glowing endorsement of the candidate. He ended by saying, “For me, a few hours ago, this campaign came to an end. For all those whose concerns have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope lives on, and the dream will never die.” The divisions exposed at the convention were not the only cause of Carter’s loss to Reagan: American hostages captured in Iran and “stagflation” were key. But disunity did not help.

The main reason that even these contentious conventions required a single ballot, and most of the others are displays of party unity, is that for all its flaws, the primary-driven nominating process works. In state-by-state contests, unsuccessful candidates — who can’t win or place in key races, who see the money dry up — can’t easily claim that they’ve been robbed. The candidate emerges clean and uneventful, and the process provides time and opportunity for wounds to heal between partisan factions.

There is no doubt that Democrats are deeply divided over whether Joe Biden is the best choice for the party in an existential election against a Republican candidate who promises a retributive presidency and dictatorship from day one. But should Biden withdraw, the party needs an alternative to a pitched battle in Chicago.

The obvious path is to simply pass the torch to Vice President Harris and make the convention one where Democrats can have the thrill of choosing a new running mate while also directly defending Biden and Harris’s record and democracy, reproductive rights, and political integrity. The only other option would be a more controlled mini-contest — about three weeks of debates with perhaps three or four candidates, followed by ranked-choice voting at the convention. But that path has its own drawbacks: Who would choose which candidates, and would it set in motion a mechanism for expedited ranked-choice voting on the convention floor?

There's no way to sugarcoat the mess Democrats find themselves in right now, but they need to keep it from getting any messier — and soon.

Norman J. Ornstein is a fellow emeritus at the American Enterprise Institute and co-host, along with Kavita Patel, from the podcast “Words Matter.”