Mexico City — Every day, an army of trucks deliver tens of thousands of pounds of fresh fruits and vegetables to Mexico City's Central de Abasto, one of the largest wholesale food markets in the world.

Most products make their way into people's kitchens and eventually into their stomachs. But every day about 420 tons spoil before they can be sold. It ends up, like so much food around the world, in a landfill.

Globally, a staggering third of all food produced is never consumed. That waste (more than a billion tons a year) fuels climate change. As organic matter decomposes, it releases methane, a greenhouse gas that is much more powerful than carbon dioxide at warming the planet.

The United Nations estimates that up to 10% of all man-made greenhouse gases are generated by food loss and waste. That's almost five times the emissions of the aviation industry.

For many years, scientists and policymakers have focused heavily on addressing other factors driving climate change, especially the burning of fossil fuels, which is by far the largest contributor to global emissions. .

But lately food waste has attracted more international attention.

The issue was on the agenda at this month's United Nations climate summit in Azerbaijan, where for the first time leaders signed a declaration calling on countries to set concrete targets to reduce methane emissions caused by organic waste.

Discarded products pile up in a trash container at Mexico City's Central de Abasto, a giant wholesale market.

(Kate Linthicum/Los Angeles Times)

Only a handful of the 196 countries that signed the Paris Agreement on climate change have incorporated commitments on food waste into their national climate plans, according to the Waste and Resources Action Program, a nonprofit organization based in the United Kingdom.

Many more nations are like Mexico, which is just beginning to evaluate how it can reduce the 20 million tons of food wasted here annually.

A recent World Bank report identified several waste hotspots in the country, including the Abasato Central, which stretches across 800 acres on the south side of the capital.

In the dense maze of stalls, the most attractive produce is prominently displayed: ripe bananas, glistening limes, and neat rows of broccoli and asparagus. In the back are fruits and vegetables that no longer look perfect: mushy papayas, wilted spinach, and bruised tomatoes.

A few years ago, market organizers launched an initiative to collect products that look too old to sell but are still perfectly usable. They donate it to food banks and soup kitchens. Organizers say they have reduced the amount of food thrown away by about a quarter since 2020 and provided food to tens of thousands of hungry people.

“It's much better to donate,” said Fernando Bringas Torres, who has been selling bananas at the market for more than four decades. “This food still has value.”

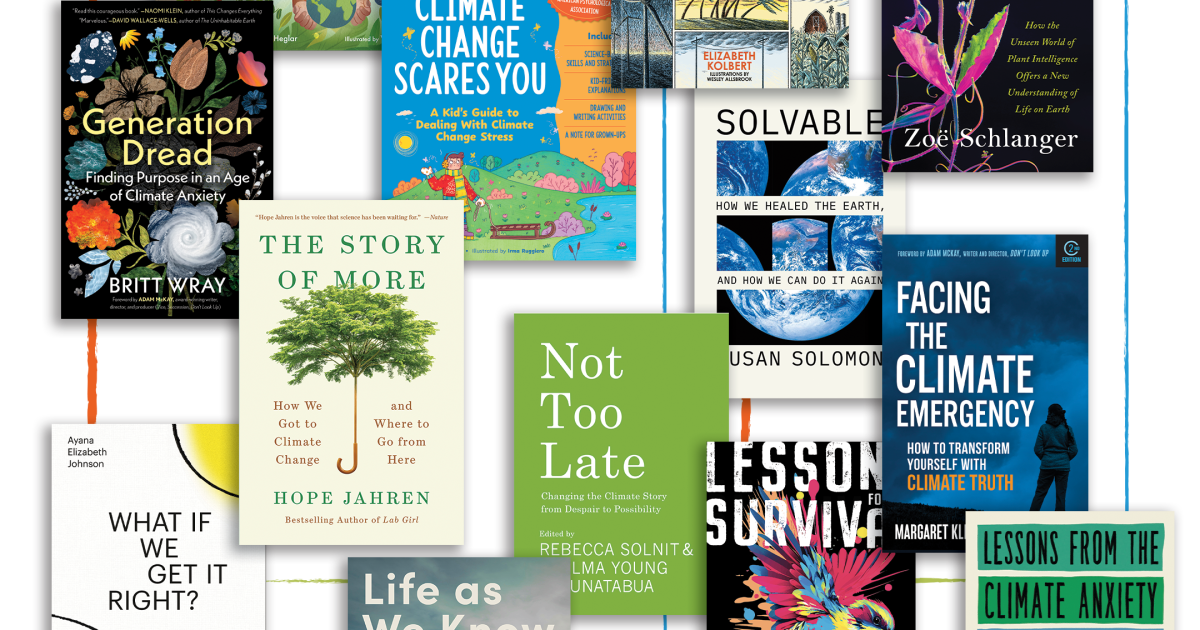

Environmental activists say reducing food waste is one of the most achievable climate solutions, in part because it is not politicized.

Asking companies and consumers to reduce the consumption of food they send to landfills is much less costly than urging a reduction in meat consumption, energy use, or the number of gasoline-powered cars.

“People on both the left and the right have a visceral reaction because it's a waste of resources,” said Christian Reynolds, a researcher at the Center for Food Policy at City University in London. Reducing waste “is not a silver bullet” to stopping global warming, Reynolds said. “But it's right up there with the things that need to be solved, and it's a useful way to open doors around climate change.”

Scientists say reducing waste is valuable because methane traps heat at a much higher rate than carbon dioxide.

An average of 420 tons of products spoil every day before they can be sold at the Central de Abasto in Mexico City.

(Kate Linthicum/Los Angeles Times)

Methane emissions are responsible for around 30% of the recent rise in global temperatures. UN climate leaders say reducing them is a vital “emergency brake” that will help curb the extreme weather already seen around the world today.

About 20% of methane emissions come from food loss and waste, a general term that describes all food that is produced but not eaten.

It includes crops destroyed by pests or extreme weather conditions, produce or meat spoiled in transport due to faulty packaging, and food spoiled in the market before it can be sold. It also includes all food purchased by individuals or served in restaurants that ends up in the trash.

A vendor holds peppers at the Central de Abasto market.

(Kate Linthicum/Los Angeles Times)

The data on food waste is surprising:

- It takes an area the size of China to grow the food that is wasted every year.

- Globally, around 13% of food produced is lost between harvest and market, while another 19% is thrown away in homes, restaurants or stores.

- Food waste takes up about half of the space in the world's landfills.

- An estimated 316 million pounds of food will be wasted in the United States during Thanksgiving alone, according to ReFED, a Chicago-based nonprofit. This equates to $500 million worth of food wasted in a single day.

Experts say some food waste is inevitable. Humans need food to survive and food degrades quickly. Modern food systems rely on transporting products over long distances, which increases the likelihood that some products will spoil.

But they say there are relatively simple ways to reduce waste at all stages, from producer to consumer.

The simplest thing to do is to first reduce the amount of extra food produced.

Many vendors at the Central de Abasto in Mexico City donate their products to food banks.

(Kate Linthicum/Los Angeles Times)

But other solutions include fixing inefficient machinery that makes it difficult to harvest all crops, improving poor roads that prevent food from getting from farm to table, and improving packaging so food stays good for longer. time.

At the end of the chain, restaurant workers may be better trained to prepare food in ways that avoid waste. Retailers can be encouraged to avoid excessive purchasing and end the practice of stocking only perfect-looking products and discarding the rest. And consumers can be encouraged to eat everything they buy and lower the temperature of their refrigerators to delay food spoilage.

There has also been a big push to get retailers to change the way they label food, as many consumers throw away products if they are past their sell-by date. “We should ensure that our food security policies do not get in the way of our climate goals,” Reynolds said.

California Governor Gavin Newsom recently signed a bill, AB 660, that would prohibit food sellers from using the term “sell by” on packages, forcing them to switch to “use by” or “best if.” is used before.” Proponents say it would discourage Californians from throwing away food that's still good.

Every day, an army of trucks deliver fresh fruits and vegetables to Mexico City's Central de Abasto, one of the largest wholesale food markets in the world.

(Kate Linthicum/Los Angeles Times)

Other efforts focus on recovery and redistribution: getting food that is about to spoil into the hands of hungry people. Every year, 783 million people around the world go hungry and one-third of the world's population faces food insecurity.

World leaders “are starting to make the connection between climate impact and social impact,” said Ana Catalina Suárez Peña, an advocate with the Global FoodBanking Network, which works with food banks in more than 50 countries.

His organization recently developed a calculator for food banks and businesses that allows them to measure the volume of methane avoided by curbing food waste.

The group found that six community-led food banks in Mexico and Ecuador avoided a total of 816 metric tons of methane over one year by redistributing food that would otherwise have gone to landfills. This is equivalent to keeping 5,436 cars off the road for a year.

Tools to measure food waste (and the savings generated by avoiding it) are an important part of addressing the problem, said Oliver Camp, food systems advisor at the COP summit.

Although he was encouraged by the summit declaration calling on countries to set targets to avoid food waste in their climate plans, he said there was still much progress to be made. Countries should implement a “comprehensive, costed national strategy, based on data on where food loss and waste occurs, and evidence-based interventions to prevent it,” he said.

The World Bank's analysis of Mexico found that the majority of the country's emissions come from the energy and transportation sectors, but that wasted food here is the fifth largest contributor.

“There is overproduction on the part of farmers,” said Adriana Martínez, 48, who runs a stall at the Central de Abastos that she inherited from her late father. He said customers “just want food that looks perfect.”

Every week, about 30% of your product starts to spoil. In the past, I would have sent it to the overflowing garbage bins behind the market. But now she calls a market organizer who puts her in touch with a local food bank.

Martinez said his father, who grew up poor, would be happy to know that food from the stand helps other people instead of rotting in a landfill. “He knew hunger,” she said. “And he hated waste.”

The Central de Abasto in Mexico City is filled with rows after rows of fruits and vegetables imported from 20 countries.

(Kate Linthicum/Los Angeles Times)