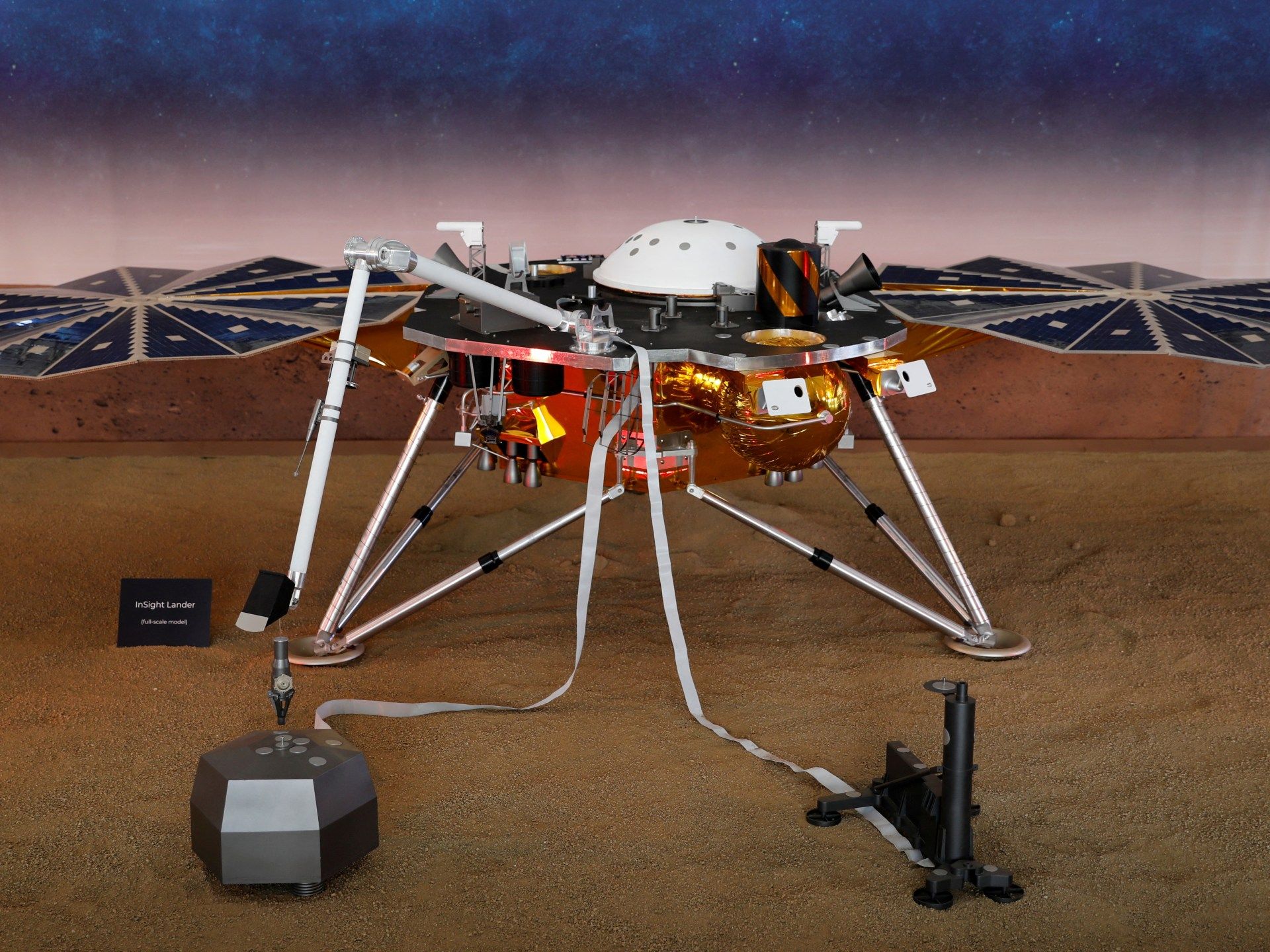

The findings come from analysis of seismic readings from NASA's Mars InSight lander before its shutdown in 2022.

New research suggests there could be enough water hiding in cracks in subterranean rocks beneath the surface of Mars to form an ocean.

The findings are based on seismic measurements from NASA's Mars InSight lander, which detected more than 1,300 earthquakes before shutting down two years ago.

Researchers combined computer models with InSight data, including earthquake speeds, to determine that the most likely cause of the seismic readings was groundwater. The results were published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The water, in fractures between 11.5 and 20 kilometers below the surface, likely accumulated there billions of years ago when Mars was home to rivers, lakes and possibly oceans, according to lead scientist Vashan Wright of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego.

“On Earth, what we know is that in areas with enough moisture and enough energy sources, there is microbial life deep underground,” Wright said. “The ingredients for life as we know it exist in the Martian subsurface, if these interpretations are correct.”

Matthias Morzfeld of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Michael Manga of the University of California, Berkeley, also co-authored the paper.

InSight Lander (Interior Exploration by Seismic Investigations, Geodesy, and Heat Transport) was the U.S. space agency's first spacecraft dedicated to looking beneath the surface of Mars and studying its interior.

If InSight's location in Elysium Planitia, near Mars' equator, is representative of the rest of the Red Planet, the groundwater there would be enough to fill a global ocean 1 to 2 kilometers deep, Wright added.

Drills and other equipment would be needed to confirm the presence of water and look for any potential signs of microbial life.

Scientists have been analyzing data collected by the lander in search of more information about the interior of Mars.

More than 3 billion years ago, Mars was almost entirely wet and is thought to have lost surface water as its atmosphere thinned, turning the planet into the dry, dusty world we know today.

Scientists theorize that much of this ancient water escaped into space or remained buried.