A new analysis of genetic material collected at a live animal market in Wuhan in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic strengthens the hypothesis that the outbreak originated there when the coronavirus jumped from infected animals to humans, scientists said.

He RecommendationsThe findings, reported in Cell, do not identify any specific infected animal that brought the SARS-CoV-2 virus to a Chinese city inhabited by more than 11 million people. Nor do they definitively prove that the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market was ground zero for a pandemic that has resulted in More than 7 million deaths.

But genetic evidence shows the market met the conditions needed to spark an outbreak and makes it increasingly difficult to explain how the coronavirus could have emerged from a lab, a farm or even another of the city's four live animal markets, the study's authors said.

“It’s as if a gorilla virus emerged in San Diego and first affected people who worked at the San Diego Zoo and lived nearby, and then spread more widely,” said Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona who worked on the study. “It wouldn’t be hard to reason that it most likely came from the zoo’s gorillas.”

The root cause of the pandemic has been the subject of intense debate since its inception. Wuhan is home to a government lab where scientists are studying coronaviruses similar to SARS-CoV-2, a fact that led politicians, national security experts, late-night talk show hosts, and many scientists (including Worobey) to wonder whether the virus had leaked from the lab.

As compelling as the argument may seem, no hard evidence has been found to support the leak hypothesis. Meanwhile, more information has come to light that has convinced scientists with expertise in relevant fields that the virus that causes COVID-19 originated in animals, just like the viruses that cause SARS, MERS, and influenza.

The new results continue that trend, he said. Dr. Dominic Dwyermember of the international working group that investigated the origins of the pandemic for the World Health Organization.

“If you put all these hypotheses about the origin, some of them become stronger as we get more evidence,” said Dwyer, a medical virologist at the University of Sydney and Westmead Hospital in Australia who was not involved in the latest work. “This paper has more evidence supporting the animal origin through the Huanan market.”

The analysis published Thursday was based on genetic data extracted from hundreds of samples collected in and around the Huanan market by researchers at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention shortly after the market closed on Jan. 1, 2020. The Chinese team detected the coronavirus in 74 of the environmental samples they analyzed, according to their report last year in the journal Nature.

Worobey and his colleagues looked further into that data. Using two different genetic sequencing techniques, they looked for fragments of SARS-CoV-2 as well as DNA from animals and people.

They then plotted what they found on a map of the sprawling market, allowing the team to reconstruct how a few initial infections could have escalated into a global health emergency.

Among the 585 samples collected in early January 2020, those containing the coronavirus were concentrated in the southwest section of the market, which was the area where wild animals were kept in cages for sale.

“The market covers a couple of acres, and this is down to one corner of the market and a couple of stalls,” Dwyer said. “That fits with an animal source. If it was coming from people wandering around the market, you’d find it everywhere.”

One market stall “stood out,” the study authors wrote. It had evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in several places: on at least one cart, in an iron container, on the floor and on a machine used to remove hair and feathers. The researchers called it “wildlife stall A.”

Another 60 samples were taken from the market's drainage system in late January 2020. Researchers found genetic evidence of the coronavirus in four of them, including one in front of the A.

As of mid-February, that drain continued to test positive for SARS-CoV-2, as did two downstream drains that may have been contaminated with runoff water from wildlife barn A, the researchers wrote.

Samples from the stall that contained the coronavirus also contained DNA from a variety of animals, including dogs, rabbits, bamboo rats, Malayan porcupines and masked palm civets. The most abundant DNA was from raccoon dogs, and some was detected on a nearby garbage cart that also tested positive for the virus.

The closest known relatives of SARS-CoV-2 that exist in nature are coronaviruses circulating in horseshoe bats in southern China, Laos, and Vietnam and in pangolins in southern China. But no bat or pangolin DNA was found in any of the samples from the Huanan market.

Raccoon dogs, masked palm civets, hoary bamboo rats and Malayan porcupines have already transmitted bat coronaviruses, the study authors noted. Could they have done so in Wuhan? they wondered.

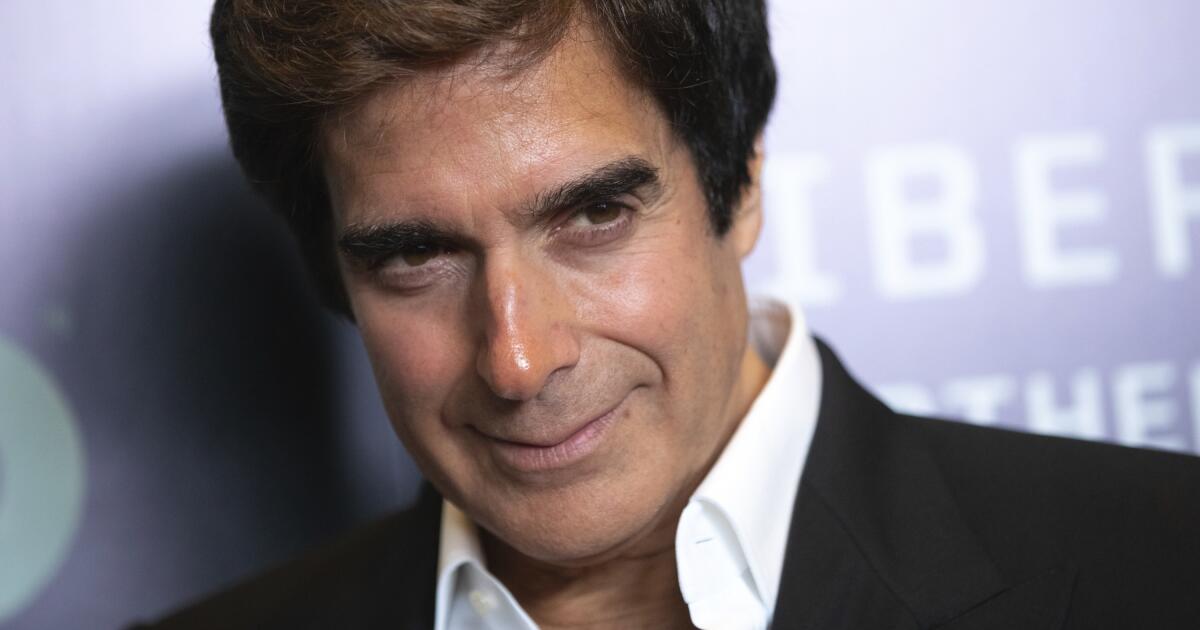

Security guards stand in front of the closed Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, on January 11, 2020.

(Noel Celis / AFP via Getty Images)

It's unclear whether bamboo rats or Malayan porcupines can be infected with SARS-CoV-2, the study authors wrote. There's no strong evidence that masked palm civets can contract the virus, but cell lines from the animals were susceptible in laboratory experiments.

On the other hand, raccoon dogs are known to contract and transmit SARS-CoV-2 and were the most abundant animal in the wild animal stable A.

The researchers analyzed the DNA of the raccoon dogs to see if they might have come from southern China, where they might have interbred with bats. They couldn't determine, but they were able to rule out a connection with raccoon dogs living on fur farms in northern China.

Worobey and his colleagues also studied animal viruses other than SARS-CoV-2 that were detected in wild animal stables to see if they offered clues about the origin of the infected animals.

A kobuvirus that infected civets at the Huanan market was closely related to a virus detected in animals sold in Sichuan and Guangxi provinces, which are closer to the territory of horseshoe bats and pangolins. And a betacoronavirus that infected bamboo rats had a close relative at a bamboo rat farm in Guangxi, one of two southern provinces where market vendors were known to source the animals.

“These findings suggest some movement of infected animals from southern China to Wuhan, a trade route that could also have led to the emergence of SARS-CoV-2,” the study authors wrote.

To determine that, more research will be needed, including fieldwork to collect animal samples in China, said Florence Débarre, an evolutionary biologist at France's National Centre for Scientific Research in Paris and lead author of the study. Worobey said she plans to continue pursuing this line of research.

Dwyer praised the effort to determine where the animals at the market came from and, by extension, how the virus could have reached the market.

A second line of evidence also supports the hypothesis that the pandemic had a so-called zoonotic origin, the scientists said.

Among the samples collected at the Huanan market on January 1, 2020, researchers were able to identify four nearly complete SARS-CoV-2 genomes. One of them was from the so-called lineage A and the other three from the closely related lineage B.

Researchers couldn’t determine whether those viruses were spread by animals or people, but the lineage A sample came from a job where a worker sought medical care in mid-December 2019. Though that was weeks before COVID-19 had been recognized as a disease, a World Health Organization report later described the worker as a possible early patient.

Confirming the presence of both strains in the market allowed the team to compare their genomes and work backwards to determine when the two strains diverged and what their most recent common ancestor looked like. They came up with six candidates, some of them more plausible than others.

There was a 99% chance that one of the four most likely candidates was correct, and those four had something important in common: They were “equivalent or identical” to the most recent common ancestor of the pandemic as a whole, said study leader Alexander Crits-Christoph, an independent computational microbiologist.

That’s what would have been expected if the outbreak had started at the Huanan market, the study authors said. In that scenario, one or more animals infected with the virus arrived at the market in November or early December. The virus then spread among animals kept in close quarters, as well as among their human caretakers. Those conditions would have given the virus the multiple opportunities it needed to establish itself in people and begin spreading among its new hosts in a densely populated city.

Moreover, it is becoming increasingly difficult to fit all this evidence into a coherent story showing the coronavirus entering China via imported frozen food (as the Chinese government has claimed) or escaping from a virology lab with lax biosafety protocols (as some in the U.S. intelligence community have proposed), Dwyer said.

“We have not added anything to support the lab leak or frozen food theory,” he said. “It just continues to reinforce the animal and market hypothesis.”

Given that the pandemic began in a city with a virology lab where scientists study coronaviruses, it makes sense to wonder if that's more than a coincidence and question whether incriminating evidence is being covered up, DéBarre said.

“A lot of us were very open to this idea,” he said. “But then the data accumulated and it all points in the same direction: it all points to the market.”

“In science, you rarely have definitive answers,” he added. “You say, ‘With all the data we have, this seems to be the most likely interpretation.’”