Mexico has elected its first female president: a U.S.-educated climate scientist and former mayor whose landslide victory Sunday reflects both the continued dominance of the country's ruling party and the great strides made by women in politics here.

That Mexico has a female leader before the United States and most other countries in the world is no coincidence.

For years, Mexico has required political parties to ensure that female candidates represent at least 50% of all competitors in federal, state and municipal elections.

It has transformed politics: more than half of the members of Congress and almost a third of the governors are women, and women head the Supreme Court and the ministries of the Interior, Education, Economy, Public Security and Foreign Affairs.

Political scientists say female leaders have helped push some of Mexico's most progressive policies, including a federal law giving domestic workers the right to social security and the decriminalization of abortion in several states before the Supreme Court ruled last year that it should be allowed nationwide.

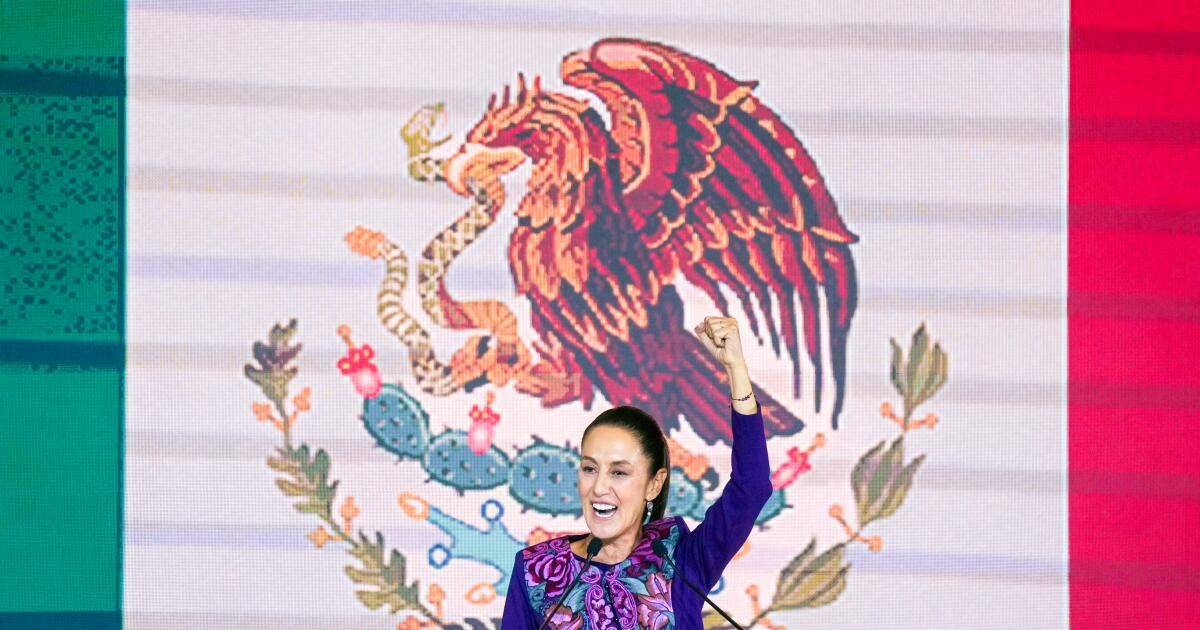

Supporters of President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum celebrate early Monday in the Zócalo, Mexico City's main square.

(Marco Ugarte / Associated Press)

The election of Claudia Sheinbaum breaks the last glass ceiling in politics in a country where women were prohibited from voting until 1954 and where a culture of sexism and high rates of violence against women still prevail.

“In 200 years of the Mexican republic, I have become the first female president,” Sheinbaum, 61, told supporters in her acceptance speech Sunday night, describing her victory as a victory for all women. .

“I didn't arrive alone,” she said. “We all arrived.”

He is scheduled to be sworn in on Oct. 1, taking command of a prosperous but polarized nation plagued by widespread gang violence.

Sheinbaum has vowed to continue the path laid out by outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a populist widely known as AMLO who helped reduce poverty by doubling the minimum wage and expanding the country's welfare system, while granting extraordinary new powers to citizens. military and failed to stop the cartels. violence.

She backs some of his most divisive proposals, including a series of constitutional changes that critics worry will erode democratic checks and balances.

Her extraordinary margin of victory (she got more than twice as many votes as her main competitor) was largely seen as a vote of confidence for López Obrador and the party he founded, Morena.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador greets his supporters in 2019 with the then mayor of Mexico City, Claudia Sheinbaum.

(Fernando Llano/Associated Press)

But how Sheinbaum will navigate under his long shadow is already the central question of his presidency. López Obrador has vowed to retire from politics, but many wonder if he will find a way to stay in the race that has animated his entire adult life.

Sheinbaum, for her part, has dismissed the implication that she will be the former president's puppet, calling it sexist. “There is a hint of misogyny, of machismo there,” she said in an interview.

Veteran Mexican journalist Jorge Zepeda Patterson suggested that Sheinbaum is up against a lot.

“The generals, the union leaders, the party leaders, the directors of the business chambers… are not just men, they operate culturally with patriarchal codes,” he wrote in the Spanish newspaper El País.

Sheinbaum owes her political career to López Obrador, who was mayor of Mexico City when he plucked the then-university professor from academic obscurity and named her his Secretary of the Environment.

He then promoted successive electoral proposals that catapulted Sheinbaum to his former position as mayor of the capital and, now, to succeed him as president.

Sheinbaum's usual campaign speech regularly refers to his tutor in all things political as the “best president” of Mexico. She borrows the slogan from her promising to “put the poor first.”

“It's hard to believe” that López Obrador will stay completely out of politics, said Lila Abed, acting director of the Mexico Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington. “But he will probably allow [Sheinbaum] defend their own positions on certain issues.”

One is energy policy. López Obrador has invested billions of dollars in refinery projects and propping up the industrious state oil giant, Pemex.

When asked how his policies might differ, Sheinbaum inevitably refers broadly to his scientific background, which includes a doctorate in environmental engineering and four years of study at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California.

“I'm a scientist, I've always worked for renewable energy sources,” she said in an interview last year with the Los Angeles Times. “I am a woman. I believe in scientific development as part of national progress.”

His adherence to science was evident from the early days of the pandemic, when López Obrador defied social distancing recommendations and toured the country, touching meat with his admirers, hugging and kissing his followers, and urging his compatriots to keep eating. in restaurants.

Sheinbaum, who at the time was mayor of Mexico City, was one of several experts credited with working behind the scenes to persuade the president to change course and embrace mask-wearing and greater caution. .

“She urged people to wear masks, shut down the city and favored social distancing at a time when AMLO was saying the opposite,” Abed said.

Experts said Sheinbaum is also likely to take a more pronounced stance than her predecessor on gender issues, an area that activists routinely accused López Obrador of neglecting.

Her criticisms have often extended to Sheinbaum as well, although she spoke out against violence against women and the grim statistic that an average of 10 women are murdered every day.

In 2022, he promoted the arrest and prosecution of the alleged murderers in one of the most notorious cases in the country: the murder of Ariadna Fernanda López Ruiz, whose battered body was found lying on a road on the outskirts of the capital. Sheinbaum alleged a cover-up by a state prosecutor, who was later indicted in the case.

Early results suggested Sheinbaum won a larger share of the vote than any candidate in decades.

As of Monday afternoon, he was winning with 59% of the vote, compared to 28% for his closest rival, Xóchitl Gálvez Ruiz, a former senator on a ticket with a coalition of opposition parties largely united against López Obrador. .

With two women at the helm, it was clear for months that Mexico would elect a woman president.

A supporter of President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum awaits her arrival at the Zócalo, Mexico City's main square, in the early hours of Monday after the election.

(Matías Delacroix / Associated Press)

Many credited activists' work that led to gender quotas, an effort that dates back to the country's transition to democracy.

After more than seven decades of rule by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, politicians began rewriting laws in the 1990s to make elections fairer. Feminist activists saw an opportunity.

Lawmakers first set a mandatory 30% quota for female candidates in the 2003 election and then raised the threshold to 40% for the 2009 election.

For a time, parties tried to evade the requirements, running women in losing districts or making secret deals for female candidates to resign once elected and hand over their seats to men.

In response, female politicians across the ideological spectrum formed a coalition to push back, take parties to court and pressure election officials to strengthen quota rules.

According to an analysis by the Pew Research Center, less than a third of United Nations member states have ever had a female leader.

Jennifer Piscopo, a professor of gender and politics at the University of London who studies Mexico, said her research shows that having women in public office shapes not only policy but also culture.

“Even if all forms of gender equality are not resolved, I think it is important that now there are no girls in Mexico who think that a woman cannot be president,” she said.

Cecilia Sánchez Vidal of The Times' Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.