When Kamala Harris took office to replace the faltering Joe Biden on the Democratic ticket, there was great fear within her party.

The only basis many had for judging Harris was her performance as vice president, which was shaky before hitting her stride a few years after taking office, and the failed campaign she waged for president in 2020, which fizzled out long before any votes were cast.

Harris quickly allayed those concerns, at least among fellow Democrats. Her charismatic campaign style has shone at rallies that have drawn packed crowds. She headlined a top-notch political convention in August and easily out-voted Donald Trump earlier this month in their only — and arguably only — debate.

Still, the hangover from her failed 2020 campaign lingers, given Harris’s leftward shift and the positions she took on issues like health care and immigration, which Trump and other Republicans have eagerly used to portray “Comrade Kamala” as the ideological stepdaughter of Karl Marx and Chairman Mao.

Polls show that one of Harris’ biggest weaknesses in this early presidential campaign is the perception that she is “too liberal,” as nearly half of respondents in a recent ABC/Ipsos poll said.

What is striking is that Harris has never been the radical leftist that her 2020 campaign positioning would suggest, or that some might attribute to her background in the progressive climate of San Francisco, where Harris began her political career by winning election as district attorney.

“She’s center-left,” said Dan Morain, a former Times staff writer and author of the biography “Kamala’s Way: An American Life.”

“That's what it was like in San Francisco. That's what it was like when he ran for office. [state] “The attorney general… is a prosecutor,” Morain said, and while prosecutors are not necessarily conservative, “they are generally more conservative than your average Democrat.”

It was political expediency — or, as some close to Harris prefer, necessity — that led her to take her leftist position.

An aide to Harris, who has known the vice president for years, described the 2020 Democratic primary as a series of ideological litmus tests and a competition to see how many of the liberal elements of the large field of competing candidates could deliver. The aide agreed to speak candidly in exchange for anonymity, to preserve his relationship with the Democratic nominee.

“If you checked those boxes,” he said, “you might live to see another day.”

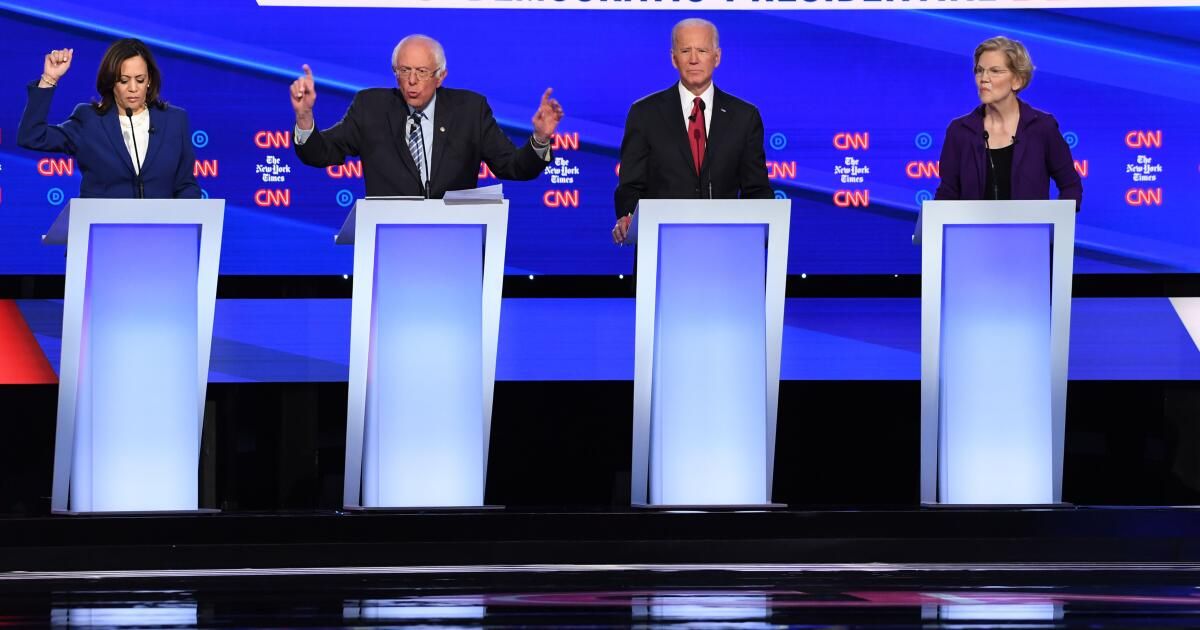

Another longtime member of Harris’s political circle, who was similarly cautious when discussing her 2020 campaign, said “there was a perception that the path to the nomination was only about running on the left” and managing to “out-Bernie” and “out-Warren” the race. (Those would be progressive totems Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren.)

Not only did that decision prove to be a strategic miscalculation, as pandemic-panic voters turned to the more centrist Biden, but for Harris it was a sham. She was trying to be something she wasn’t, said this other longtime observer. Worse, “she ended up adopting a bunch of positions that ultimately left her with nothing but ballast four years later.”

It's funny how this works.

As part of her makeover, Harris backed eliminating the country’s private health insurance system, supported a ban on fracking, called for drastic cuts to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency and said she was open to a “conversation” about allowing violent criminals to vote from their cells. CNN’s Andrew Kaczynski recently surfaced a 2019 ACLU questionnaire in which Harris supported taxpayer funding of gender transition surgeries for detained immigrants and federal prisoners.

Harris long ago abandoned her positions on health care, immigration, and fracking. She abandoned her stance on prison voting the next day. In response to Kaczynski’s inquiry, Harris’s campaign offered this response, a masterpiece of opacity: “The Vice President’s positions have been shaped by three years of effective governance as part of the Biden-Harris administration.”

As for Harris, she has acknowledged having changed some of her positions, but insists: “My values have not changed.”

But his political image certainly has. After eschewing the image of a dogged prosecutor in the 2020 race, when criminal justice reform was a hot-button issue for many Democrats, he is now making law and order a central element of his White House bid.

Obviously, there is a big difference between running in a primary, when a party’s most ideological voters have the clout, and campaigning in a general election, which requires appealing to a broader segment of Americans. Harris has benefited greatly from her overnight nomination as the Democratic nominee, which has spared her the need to genuflect so conspicuously to the political left.

But given her willingness to do just that the last time she ran for president — even if it meant going against her more centrist leanings — voters are not wrong to wonder where Harris stands and how firmly she will stick to the values she professes to hold dear.

In 2002, as a senator from New York, Hillary Clinton voted to give President George W. Bush the authority to invade Iraq. At the time, it seemed like a politically sensible move for someone who was considering a future presidential run and wanted to avoid the image of a pushover that had plagued Democrats since the Vietnam War.

As it turned out, Clinton's vote was a key reason she lost the Democratic nomination in 2008 to then-Senator Barack Obama, a staunch opponent of the Iraq War.

All these contortions of the candidates bring to mind a verse from Hamlet: Be true to thine own self.

It's a good recipe for life. And for politics too.