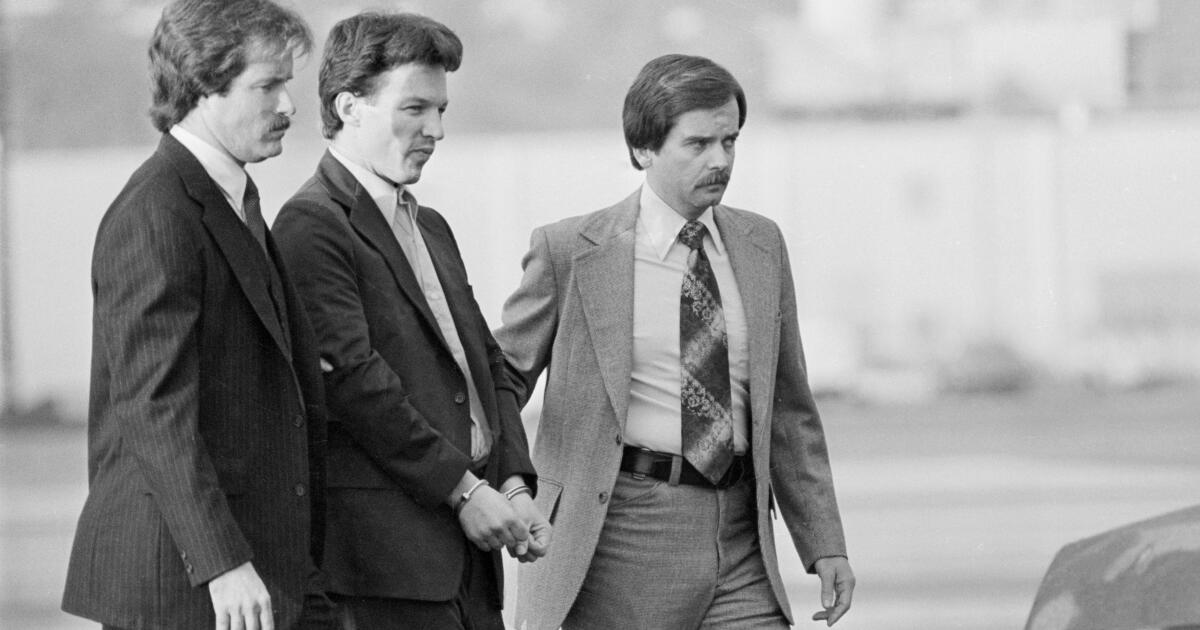

In the early hours of June 4, 1989, Chinese soldiers — under orders from the country's leader, Deng Xiaoping, to clear pro-democracy protesters from Beijing's Tiananmen Square — opened fire, killing hundreds of people.

Times reporter David Holley watched from a nearby hotel window, using a phone in a coffee shop to report what he saw to colleagues in the Beijing office, as gunfire rang out in the background.

Three decades later, in an article reflecting on what he saw and why it remains one of the most pivotal moments in modern Chinese history, he wrote: “This Beijing massacre finally strengthened Deng’s grip and froze his formula for China’s modernization: one-party dictatorship combined with market-oriented reforms… Over the past 30 years, China has grown stronger and more prosperous, but the formula remains unchanged.”

For the record:

17:35 hours August 23, 2024An earlier version of this article said Holley died at his home in Nagano at age 73. He died in a Tokyo hospital at age 74.

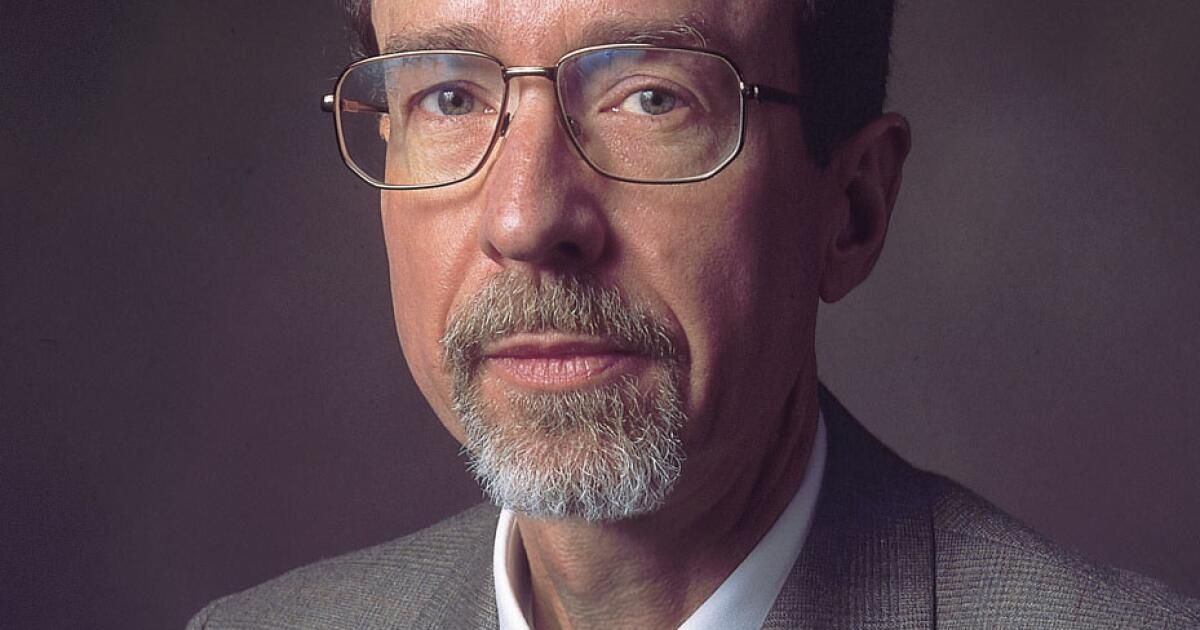

Holley worked for two decades as a foreign correspondent for The Times, covering pro-democracy street protests in nearly a dozen countries before turning to teaching. He died Aug. 4 in a Tokyo hospital at age 74. His cousin, Frederick Holley, said the cause was complications from a chronic illness.

Former colleagues remembered Holley for his friendly personality and dedication to his reporting.

“Everyone will say he was a kind-hearted person, generous and caring, honest and hard-working,” said Simon Li, a former Times editor who worked with Holley on the foreign affairs desk.

Li added that Holley’s fluency in Chinese and Japanese enhanced his work: “David’s ease in speaking the language was an asset that embellished his coverage. He added a dimension to reporting from those two countries that we may not have had before.”

Holley grew up in Rochester, New York, the youngest of three children. An Asian studies class during his senior year of high school sparked his interest in East Asian languages. After earning a bachelor’s degree in Chinese from Oberlin College, he traveled the world studying languages and working odd jobs, including at an ice cream parlor.

He met his wife, Fumiyo Asahi, while studying Spanish in Mexico. They married in Japan, where he taught English for a few years.

Holley earned a master's degree in communications from Stanford University with the goal of becoming a foreign correspondent. After graduating, she worked for The Times in Southern California for seven years before moving to Beijing in 1987.

“I wanted to go to all the places where the most people lived,” Holley told one of his former students, Jin Young Lim, in a 2021 podcast. “I was trying to consciously educate myself about places where there were a lot of people, with the idea that, over my lifetime, places with a lot of people were going to become very, very important geopolitically, internationally, to American foreign relations.”

After Beijing, Holley worked as a Times correspondent in Tokyo, Warsaw and Moscow before leaving the paper in 2007 to teach journalism, history and American politics at Waseda University and Keio University in Japan.

Lim, who graduated from Waseda University in 2018, said Holley has been the most influential person in his life.

After retiring three years ago, Holley took up farming in rural Nagano but maintained frequent communication via Zoom calls with his former students, his cousin Frederick said.

In the podcast, Holley said that as the U.S.-China relationship has become contentious, understanding the thinking of Chinese leaders and people is critical to American interests.

“For the United States to be able to get ahead in a competition with China, it’s extremely important to understand why China acts the way it does,” he said. “If American foreign policy can be based on the principle of, ‘Well, we’re going to work for what’s best for the United States, but we’re going to be smart about it, we’re going to understand our rivals,’ that’s a big step toward making conflicts less dangerous, and it’s also a big step toward stopping thinking of them as rivals and starting to think of them as us, too.”

Despite the world's enormous challenges, Holley said, he maintained a sense of optimism.

“Whatever the tensions between Washington, Beijing and Moscow, at least the leaders of these three great powers meet regularly at global summits where everyone is reasonably cordial with each other,” he said in a TEDx talk in 2014.