Covering an entire classroom wall in a Tunisian synagogue in Belleville, an immigrant shelter on the slopes northeast of Paris, are the names of 1,100 Jewish children who were arrested by French police, deported to Auschwitz and murdered by the Nazis during World War II.

The memorial to the fallen goes street by street, family by family. Among the 53 children abducted from houses a few blocks away on the rue de Belleville are Émile Rosenberg, 6, Éliane Apelojg, 5, Florence Endel, 4, and Michel Blumenkranc, 3.

“This synagogue was their home,” the monument says.

A memorial at the Rebbi Hai Taieb Lo Met synagogue in Paris names 1,100 Jewish children who were arrested by French police, deported to Auschwitz and murdered by the Nazis during World War II.

(Michael Finnegan / For The Times)

Despite this dark history, some Jews in Belleville are doing the previously unthinkable and voting in France's National Assembly elections for the far-right National Rally party, which is leading in polls for Sunday's runoff election.

One of the party's founders, Pierre Bousquet, was a French fighter in Hitler's Waffen-SS. Another, Jean-Marie Le Pen, who led the party from its birth in 1972 until 2011, dismissed the Nazi gas chambers as a “detail” of history.

Jewish support for the party is a sign of how shocked many Jews are by the record rise in anti-Semitic attacks in France since the Hamas-led assault on Israel on Oct. 7 that triggered Israel's invasion of Gaza. Last month, according to police, a 12-year-old Jewish girl was raped in a Paris suburb by three boys who tormented her with anti-Semitic insults.

It is also a measure of the extent to which the French left has angered Jewish voters with its fierce attacks on Israel and Zionism while trying to win support among French Muslims, a substantially larger group of voters.

Over lunch with friends at Chez René et Gabin, a Tunisian kosher restaurant just down the hill from the synagogue, Judith Benchetrit said she had voted for the National Rally in the first round and asked if anyone else had watched a harrowing television documentary about the Oct. 7 attack the night before.

It was her deep hatred of the far-left movement France Unbreakable and its leader, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, that led her to support the far right.

Mélenchon “campaigns for Palestine, so now he has all the Palestinians and all the Arabs of France behind him,” said Benchetrit, 32, who is unemployed.

Rue de Belleville, the street in Paris where French police arrested 53 Jewish children during World War II and deported them to Auschwitz, where they were murdered by the Nazis.

(Michael Finnegan / For The Times)

The National Rally has reinvented itself as an ally of Jews and Israel. If the party wins a majority in the Assembly, its leader, Jordan Bardella, could become prime minister, bringing France under the control of the far right for the first time since the fall of the Vichy regime, which collaborated with the German occupation between 1940 and 1944.

A more likely outcome, polls suggest, is that the party falls short of a majority but wins more seats than any other, destabilising France as various factions jostle for power.

Whatever the outcome, the snap election called by President Emmanuel Macron is certain to leave France with a parliament dominated by the far right and a far left that many Jews consider anti-Semitic.

Chalom Sayada, 60, a doctor who runs the synagogue's youth programs, said many congregants were overlooking the National Rally's lineage, but he was not buying the rebranding by party leaders.

“I don’t forget where they come from,” he said.

He described the elections as “a choice between plague and cholera.”

: :

The synagogue, Rebbi Hai Taieb Lo Met, embodies Belleville's rich history, a cycle of tragedy and renewal.

Founded in 1931 by banker Edmond de Rothschild, it was built for the thousands of Ashkenazi Jews who settled in Belleville after fleeing persecution in central and eastern Europe. Belleville is within walking distance of the Marais, the Jewish district in central Paris.

The Great Depression fostered widespread resentment against immigrants throughout France, leading to discrimination, arrests, and expulsions.

During the German occupation, the Vichy French collaborationist government banned Jews from many professions and ordered their property confiscated.

In July 1942, Belleville was one of the main targets of the Paris police in the Velodrome d'Hiver roundup. Across the city, nearly 13,000 Jews, including several thousand children, were arrested and deported to Auschwitz, where almost all were murdered.

The Hai Taieb synagogue, which had few survivors, was emptied. On another wall of the hall, the names of hundreds of adults from the congregation who were rounded up and killed in the Vel d'Hiv raid are engraved on 10 stone tablets.

But the synagogue came back to life in the 1950s, when thousands of Sephardic Jews from North Africa emigrated to Belleville as Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco gained independence from France.

Muslims from the North African Mediterranean coast also immigrated to Belleville. Their neighbours, who arrived more recently, are Chinese, Vietnamese, Cambodians, Laotians and Senegalese.

On Boulevard de Belleville, the Sabbah grocery store sells kosher and halal food, as well as guidance products. Pastry lovers will find makroudh with sesame seeds at Rose de Tunis and pains au chocolat at La Baguette des Pyrénées.

Tensions sometimes rise in the neighborhood, most recently between Muslims and Jews.

At the kosher restaurant, one-third of the customers were Arabs, according to Stéphane Bsiri, the manager. Arabs stopped coming after October 7.

“They say our money goes to Israel,” Bsiri said, exasperated. “Idiots.”

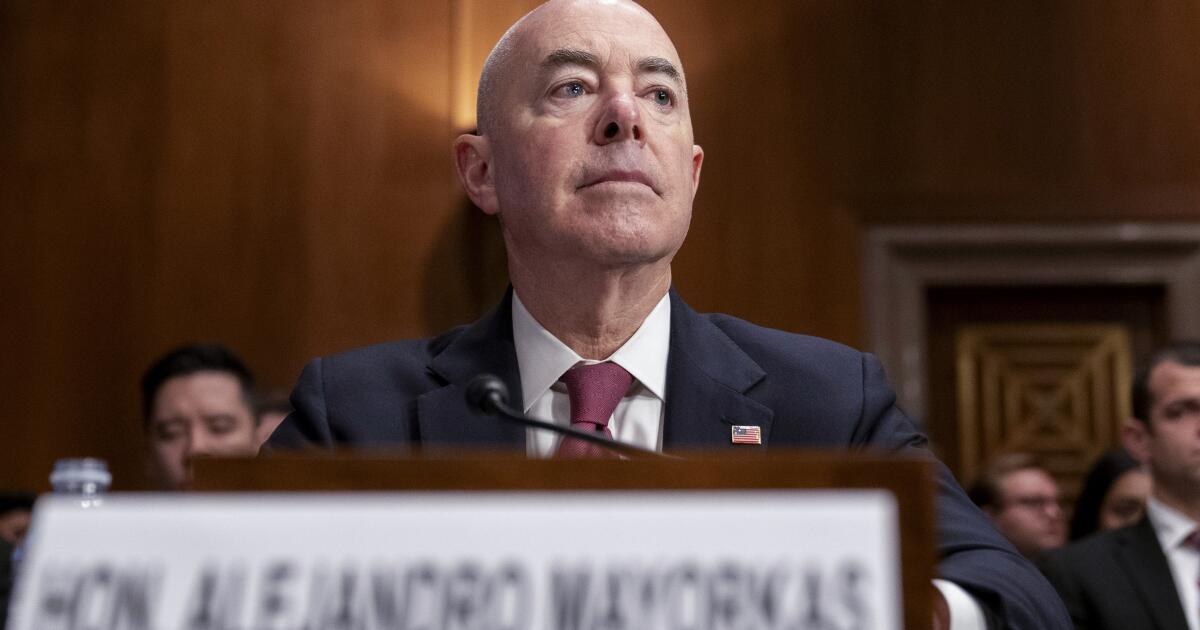

At the Chez Rene et Gabin restaurant in Paris, manager Stéphane Bsiri works the counter.

(Michael Finnegan / For The Times)

One of his clients, Sonia Lelloum, the daughter of Tunisian Jewish immigrants, said she had resisted the temptation to vote for the National Rally in previous elections because of its links to Nazism. This time, she said, she did so because she likes the party's crusade against immigration.

“I would like France to remain French,” says Lelloum, a private chef. “We are children of immigrants, but we have integrated into France, we have become French and we respect France.”

Down the street at Jojo, the kosher butcher shop his family has run for 64 years, Joseph Slama said he understands why the National Rally has attracted other Jewish voters, but he thinks its past is a disqualifier, especially when some young French people don't know what the Holocaust was.

His grandfather, who emigrated to Belleville from Tunisia in 1956, opened the butcher shop just outside the metro station, on a busy corner where young men now sell cartons of black market cigarettes for cash.

Joseph Slama works at the kosher butcher shop Jojo in the Belleville district of Paris.

(Michael Finnegan / For The Times)

Slama, who favors centrists, sees the left led by Mélenchon as a threat to France's roughly 400,000 Jews, the largest Jewish population outside the United States and Israel. What worries Slama, a father of three, most is the constant confusion between Israel, Zionism and Jews.

“It puts us in danger in France,” she said after wrapping bouquets of merguez for a customer. “I am even afraid for my children.”

: :

Anti-Semitic acts quadrupled in France last year, with a spike starting on Oct. 7, according to a report last month by the government's National Advisory Commission on Human Rights. The government has also reported a sharp rise in attacks against Muslims.

Alexandre Bande, a historian who has compiled a political history of anti-Semitism in France since 1967, said left-wing rhetoric on Gaza had clearly sparked fear among French Jews.

But he questioned the sincerity of the far right’s adoption of a friendly stance toward French Jews, most visibly with the appearance of Bardella and Marine Le Pen, leader of the National Rally and daughter of the party’s co-founder, at a march against anti-Semitism in Paris in November. Both Mélenchon and Macron did not attend the protest.

“There is no historical coherence,” Bande said, predicting that the far right will eventually “do what it has always done, which is attack the 'bad French,' and the 'bad French' could very well turn out to be Jews once again.”

While it makes sense for Jews to fear radical Islam, he said, “that doesn’t mean you should throw yourself into the arms of another wolf.”

For now, some Jews have removed the mezuzot from their doors and told their children not to wear kippahs in the street.

On Julien Lacroix Street in Belleville, no sign identifies Hai Taieb as a synagogue and a security code is required to enter the main door.

Thousands of people gather for a march against anti-Semitism in Paris on November 12.

(Sylvie Corbet/Associated Press)

“It is not marked on purpose,” said Sayada, the doctor, whose father Gaston began praying there in 1956 after emigrating from Tunisia and is now the synagogue’s president. “The Jew in France is discreet now. He has a duty to be discreet.”

That, he said, is why some synagogue parishioners support the National Demonstration.

“They want someone authoritarian to protect them,” he said.

One of the most striking illustrations of the new opening to the far right came last month, when the well-known Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld, 88, an icon to many Jews in France, told French television that if he were forced to choose between National Rally and the country's largest left-wing party, France Unbreakable, he would choose National Rally.

The synagogue's memorial in memory of the children thanks Klarsfeld for documenting their names among the 74,150 Jews deported from France.

Finnegan is a special correspondent.