Build the technology of the future. Protect the nation from attack. Buy a sports car.

These were some of the rewards of working in the semiconductor industry, 200 high school students learned at a recent day-long recruiting event for one of Taiwan's top engineering schools.

“Taiwan doesn't have many natural resources,” Morris Ker, chairman of the newly created microelectronics department at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, told the students. “You are Taiwan's high-quality 'brain mine'. You must not waste the intelligence that has been given to you.”

The island of 23 million people produces almost a fifth of the world's semiconductors, microchips that power almost everything: appliances, cars, smartphones and more. Additionally, Taiwan specializes in the smallest and most advanced processors, and they will account for 69% of global production in 2022, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association. and the Boston Consulting Group.

But the pandemic-induced chip shortage, along with rising geopolitical tensions in Asia, have highlighted the fragility of the current supply chain and its dependence on an island under the specter of a Chinese takeover.

In the United States, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China, the semiconductor industry is already short hundreds of thousands of workers. In 2022, financial and consulting services giant Deloitte estimated that semiconductor companies would need more than 1 million additional skilled workers by 2030.

Morris Ker, chair of the microelectronics department at NYCU, gives a presentation on why students should join the semiconductor industry.

(Stephanie Yang/Los Angeles Times)

Seeking to maintain Taiwan's status as the world's chip-making capital, the government and several corporations here helped the university, known as NYCU, create the microelectronics department last year to speed students' access to jobs in the industry. Now the department was recruiting its inaugural class.

Wu Min-han, 20, who was sitting in the front row with his mother, didn't need much convincing.

He first applied to college to major in mathematics, but dropped out after losing interest in the subject. He then read about the new microelectronics program and decided to apply. He is waiting to hear.

“This department could have a pretty positive impact on my future career prospects,” he said.

Others were devastated.

Lian Yu-yan, 18, said that while the new department looks impressive, she is also interested in majoring in mechanical engineering and photonics. She hopes to find a well-paying tech job after graduating college, but she wants to keep her options open.

Prospective students in a new microelectronics department at NYCU take an entrance exam.

(Xin-yun Wu / For The Times)

Her father, who accompanied her to the event, worked in the semiconductor industry and sees great potential for growth with the evolution of AI. However, that hasn't done much to persuade her daughter.

“You can't control Generation Z,” he said with a laugh and a shrug.

Many prospective students competing for the 65 spots in next semester's program cited salary and job stability among their top considerations. In Taiwan, there are few industries that can compete with semiconductors in terms of salary and prestige.

As the rise of electric vehicles, artificial intelligence and other advanced technologies demand more semiconductors, many nations are making chip self-sufficiency a top priority.

In the US, Europe and Asia, governments have announced more than $316 billion in tax incentives for the semiconductor industry since 2021, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association. and the Boston Consulting Group.

A May report from those organizations projected that private companies will spend an additional $2.3 trillion through 2032 to build more facilities that make semiconductors, also known as manufacturing plants or fabs.

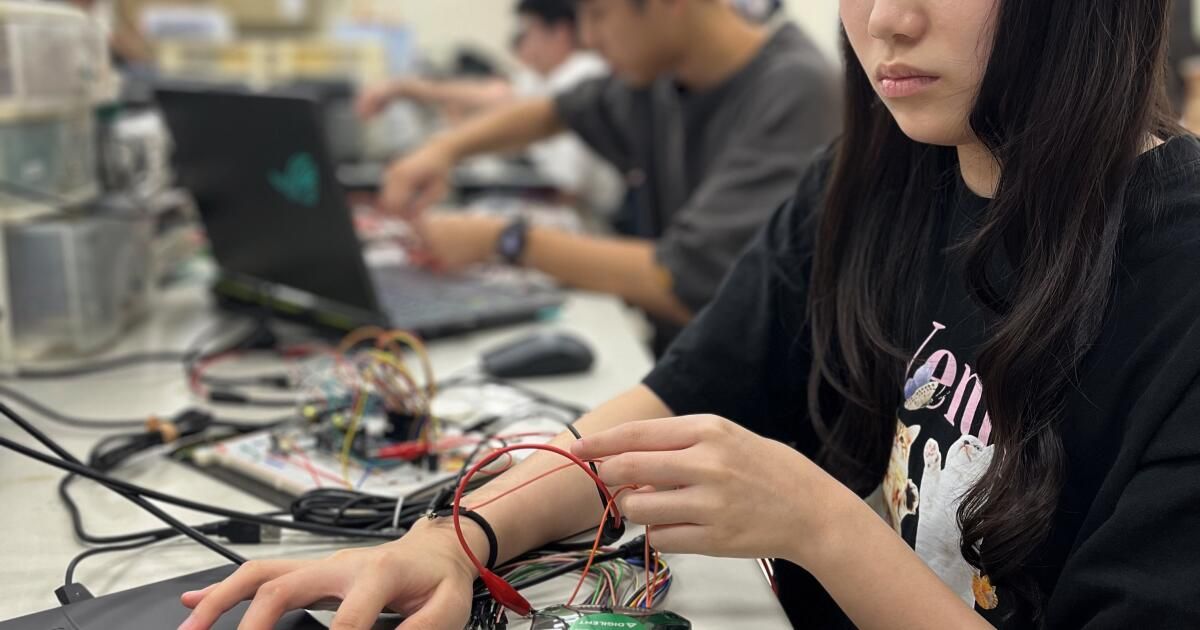

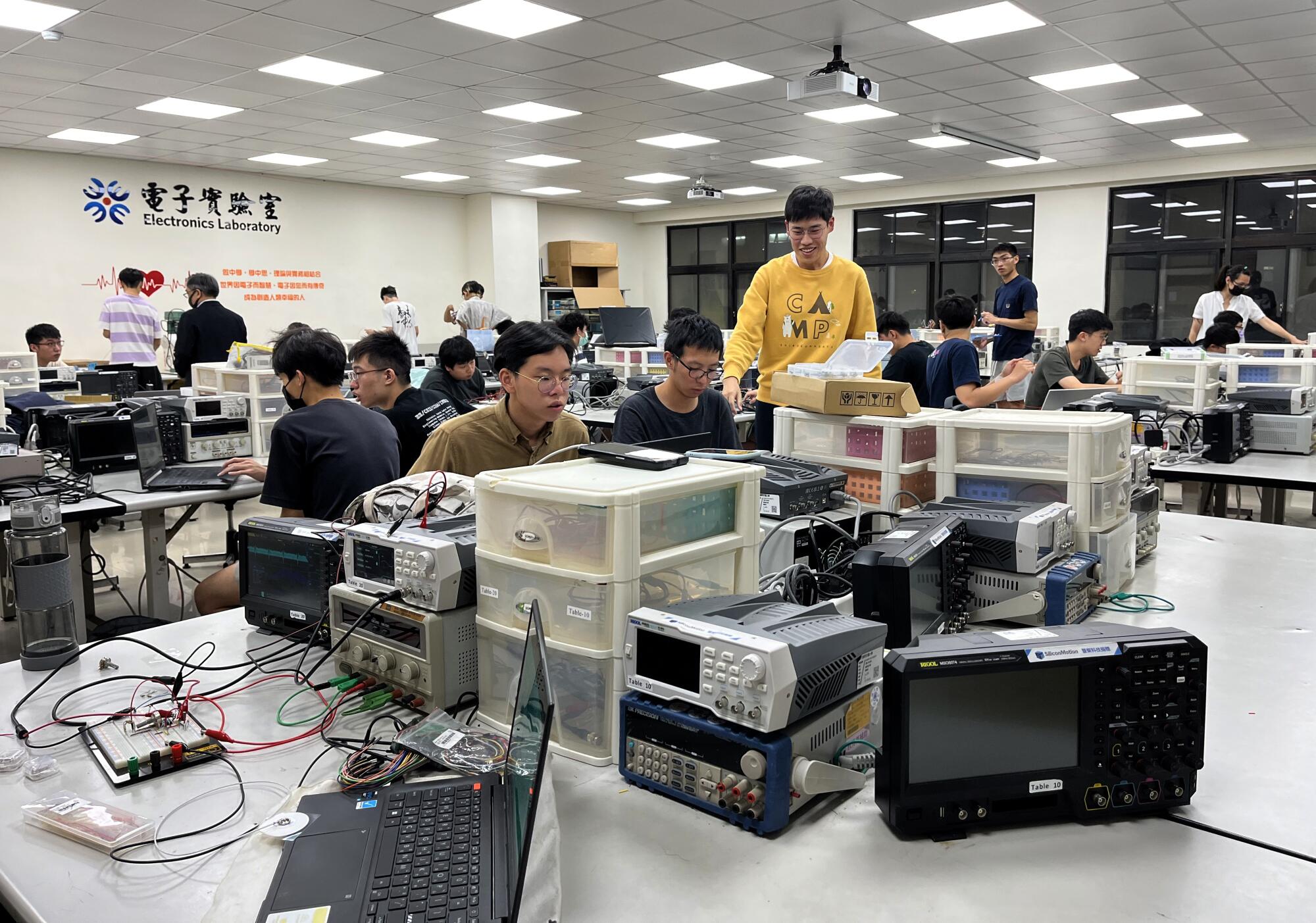

NYCU students work on building cardiac ECG monitors in the lab Thursday night.

(Stephanie Yang/Los Angeles Times)

Meanwhile, the expansion of chip manufacturing capabilities is exacerbating another shortage: that of people trained to make them.

As the global battle for talent intensifies and Taiwan loses manufacturing market share, the island has even more incentive to cultivate its next generation of workers.

Known as Taiwan's “silicon shield,” the semiconductor industry is considered so critical to the global economy that it could deter Beijing, which claims the island's democracy, from launching a military attack. Taiwanese often refer to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, the world's largest chipmaker and a major supplier to Apple, as the “sacred mountain that protects the nation.”

In his presentation, Ker gave another example of the industry's indispensability. When Taiwan's worst earthquake in a quarter-century hit in April, factory workers were evacuated but quickly returned, a sign, Ker said, of the manufacturing hub's resilience.

But for Su Xin-zheng, a second-year engineering student at NYCU, the response to the natural disaster was representative of the heavy lifting required to continue churning out so many of the world's chips.

Su Xin-zheng, a second-year student, works on his final project in the electronic engineering laboratory.

(Xin-yun Wu / For The Times)

“People are always available,” Su said, adding that he would prioritize free time over a hefty salary. “We saw everyone go back in to protect the machines.”

Industry veterans evoke brutal hours and sacrifices when describing how Taiwan built its semiconductor industry from the ground up. With dark humor they speak, metaphorically, of ruining their livers by working all night.

They fear that the younger generation will be less inclined to do such hard work.

In particular, the growing emphasis on work-life balance is eroding interest in the manufacturing plant jobs that Taiwan and TSMC are known for.

Over the past two years, demand for manufacturing labor has surpassed that for other parts of the chip-making process, such as designing circuit boards or packaging after manufacturing, according to the local hiring platform. 104 Job Bank. Engineering students enrolled at NYCU said those jobs seemed grueling, with lower salaries than research or design positions.

Ting Cheng-wei, 23, frequents anonymous online forums to learn more about salaries and job descriptions at different companies. That's why she knows that manufacturing jobs, which require full-body suits to protect against contamination and 12-hour shifts on two-day rotations, don't appeal to her.

Students attend a recruiting event for a program created to train the next generation of semiconductor workers.

(Xin-yun Wu / For The Times)

“Working in a factory seems to be a worker,” said Ting, a master's student and assistant professor at the university. “Why would I work in a factory when I can sit in an office with a higher salary?”

He speculated that the shortage of jobs at semiconductor plants could be solved simply by offering more money.

That would be enough for 19-year-old Wei Yu-han, who was ambivalent about semiconductors after his first year of studying mechanical engineering. After visiting a factory during a school trip, he thought the job seemed easy and well-paid.

“I probably brainwashed myself into liking it,” he said. “I can give up my freedom for money.”

At the end of the introductory seminar, all students present took a short entrance exam as part of their applications. Still, enrollment in the new department is restricted by another human resources constraint: Ker added that the school is also desperately looking to hire more semiconductor professors.

Special correspondent Xin-yun Wu in Taipei contributed to this report.