Raucous cheers broke out and far-right leaders flashed before the camera lenses. The vote was held: the ultranationalist Alternative for Germany (for many here, a ghostly echo of the Nazi past) was now anointed the country's second-largest political party.

Across Europe, far-right political groups made strong gains in European Parliament elections in four days of voting that ended Sunday. As predicted, centrist parties obtained the highest share of votes overall in the 27 countries of the European Union, but in several countries – especially France and Belgium – the strong nationalist-populist demonstration unleashed political earthquakes.

French President Emmanuel Macron, whose party was defeated 2-1 by the far-right National Rally party, has called early national parliamentary elections that will take place just weeks before the Paris Olympics. In Belgium, the prime minister resigned in tears after the electoral victory of a right-wing party.

And in Germany, there was growing anguish over the growing advances of the far right, which were most pronounced in the former East but were felt across a country that was reunified nearly 35 years ago after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Although France and Germany are the largest and most influential members of the bloc, analysts warned that their results do not necessarily reflect political sentiment at the continental level, as each individual EU member state has its own priorities and concerns.

And because the European Parliament has limited powers, the exercise every five years of choosing its composition can amount to a kind of protest vote, the results of which may or may not be replicated in races for countries' own parliaments and national leaderships.

Still, the balance of power in the 720-seat European Parliament shifted clearly to the right. And at least in France, the results triggered what amounted to a “national crisis,” said French political analyst Celia Belin.

“At the very least, we can say that this is tremendously disturbing and totally surprising, with absolutely unknown consequences,” Belin of the European Council on Foreign Relations said during a post-mortem webinar organized by the think tank on Monday.

Macron's political tactic of calling early elections is risky, analysts said. Although early parliamentary elections will not determine the presidency (that vote will not be held until 2027), he could be paralyzed and humiliated if the National Rally, led by his nemesis Marine Le Pen, achieves a performance comparable to that in Sunday's election. vote.

Le Pen expressed confidence that the National Rally would do just that. In the European vote, his party was represented by his protégé Jordan Bardella, 28, but she will be his face in the national parliamentary voting rounds later this month and early July.

“We are prepared to exercise power if the French give us their confidence in these elections,” Le Pen told jubilant supporters in Paris. “We are ready to transform the country, defend the interests of the French and stop mass migration.”

Migration, the economy, climate change and the wars in Ukraine and Gaza all influenced the voting results, although the European Parliament's influence on these issues is mainly indirect. It approves the EU budget as well as its executive leadership, and its positions help shape legislative agendas in the bloc's national parliaments.

Europe's far-right parties generally have in common a hard line on migration, a conservative social agenda, a reluctance to fund ambitious projects to fight climate change and a desire to erode the EU's powers from within. But they differ on some issues, including the war in Ukraine and the degree of friendship toward Russian President Vladimir Putin.

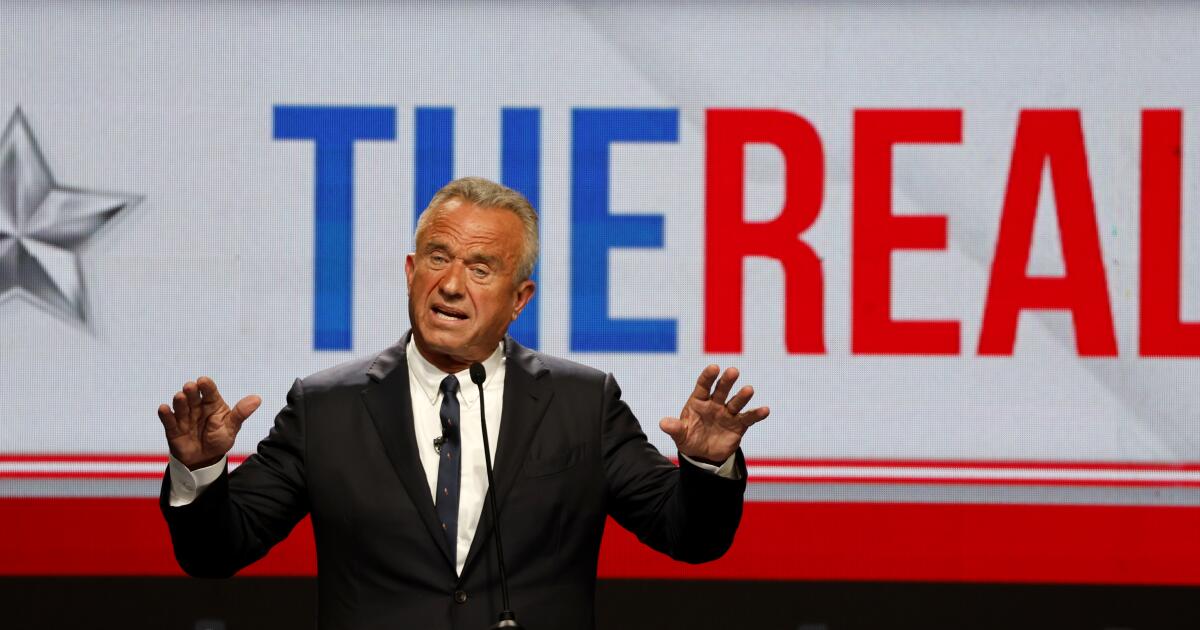

Some observers believe that a streak of anti-establishment sentiment exposed in the European vote could be a barometer for the US presidential election in November. Populist waves sometimes cross the Atlantic, as when Donald Trump's 2016 presidential election was preceded by Britain's shocking decision to leave the EU.

But others saw the vote as an assertion that, while voters may have wanted to express some symbolic discontent with the status quo, they were more comfortable leaving the real business of governing in the hands of more moderate forces.

“The center remains,” declared Ursula von der Leyen, 65, head of the bloc's executive European Commission, whose job will be at stake once the European Parliament consolidates into groups that reflect the political leanings of national parties. .

This is a process that will take a few weeks, with the new EU legislature holding its first session in mid-July.

Von der Leyen's centre-right European People's Party won the most seats, provisional results showed, followed by a centre-left group. But coalition politics could still prompt her to seek an alliance with Italy's far-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, whose party – which has neo-fascist roots – emerged as the big winner of the election, leaving her in a position to play the role of maker of political influences.

In Germany, Chancellor Olaf Sholz's center-left party suffered a tough but narrow defeat to the AfD, as Alternative for Germany is known. It suffered a much more substantial loss (by a margin of more than 2 to 1) at the hands of the main opposition, the center-right Union bloc.

Scholz's Social Democrats had their worst post-World War II result in a national vote, winning less than 14% to the AfD's turnout of around 16%, according to preliminary counts.

Still, the AfD result was alarming for many Germans, especially in light of the fact that the party was hit by several scandals before the vote that likely reduced its support, which otherwise could have been even higher.

The party, designated by German authorities as a suspected extremist group, has run into trouble with the country's strict laws on the use of Nazi symbols. Its leading candidate in the EU elections, Maximilian Krah, caused a stir by suggesting in a recent interview that some Germans who joined the Waffen SS, a Nazi paramilitary force, might have been justified in doing so.

That, combined with accusations that the AfD helped spread Russian influence, led to him being expelled from the far-right group in the European Parliament, although that move could be reversed.

But his strong showing in Sunday's vote was an unwelcome reminder to many Germans – just after European allies solemnly commemorated the 80th anniversary of D-Day, a turning point in the war against Hitler's Germany – that the AfD is now an increasingly dominant force in the country. the politics of the country.

“The most important thing the AfD has achieved is to normalize its views, views that were previously considered very extreme,” said Sabine Volk, an analyst at the University of Passau.

In recent years, Europe has become a global leader in the fight against climate change, but the vote appeared to represent an overall blow to the environmental movement.

In the EU parliament, the Greens were projected to lose almost a third of the seats they won five years ago. This echoed a retreat by the Greens in Germany, where they are part of Scholz's ruling coalition, going from winning more than a fifth of the German vote in the 2019 European elections to a projected 12% in Sunday's vote. .

Belin, the French analyst, called it a possible “green reaction” but warned that the full implications of the vote for environmental policy were not yet clear. Green parties have fared better in some parts of the continent, including Sweden and Denmark, and substantial parts of their agenda have been incorporated into the policies of larger parties.