The beginning of the end of World War II occurred 80 years ago Thursday, when approximately 160,000 allied troops made landfall in Normandy on Day D. The initial battle against some 50,000 armed Germans resulted in thousands of American, British and Canadian casualties, many of them seriously wounded.

Who would take care of them?

On June 6, 1944, the United States medical establishment had spent years preparing to treat these initial patients…and the legions of wounded warriors who would surely follow.

The medical school curriculum was accelerated. Internships and residency training were compressed. Hundreds of thousands of women were attracted to enroll in nursing schools without paying tuition.

conscientious objectors – and others – were trained to serve as combat medics, becoming the first link in a newly developed “evacuation chain” designed to get patients off the front lines and into hospitals with unprecedented efficiency. Doctors took advantage of tools such as penicillin, blood transfusions and planes equipped as flying ambulances that had not existed during the First World War.

“The nature of war was very, very different in 1944,” he said. Dr. Leo A. Gordon, an affiliated faculty member at Cedars-Sinai History of Medicine Program. “So the nature of the medicine was very, very different.”

Gordon spoke to The Times about an often-overlooked aspect of World War II.

How did you become interested in the medical aspects of World War II?

In my surgical training, I spent a lot of time in a [Veterans Affairs] hospital in boston. That was probably the beginning of what has really become a career-long interest of his in World War II in general and the medical aspects of how the United States prepared for the invasion.

As the veterans aged and the memory of June 6, 1944 diminished in impact, it simply spurred me to maintain that particular interest.

How did the United States prepare to handle the medical aspects of the war?

After the Attack on Pearl Harbor On December 7, 1941, the medical establishment was clear that we were going to need more doctors, more nurses, and more front-line combat medics.

He US Surgeon General established a division to accelerate the process of medical education. All 247 medical schools that existed at the time had accelerated graduation programs that were reduced by one year. [of instruction] up to nine months. Furthermore, the Association. of American medical schools reduced the internship year to nine months and all residencies were shortened to a maximum of two years, regardless of the specialty.

When you finished your training, there was the 50-50 program: 50% would be recruited and the other 50% would be returned to the community.

Since most of the injuries were going to be traumatic, you had a very active role on the part of the American College of Surgeons. They organized a national tour and showed doctors how to treat the injuries they would face: fractures, burns and resuscitations.

How did they know what kind of war wounds to prepare for?

They prepared to face trauma similar to what they had seen in their practices, but on a larger scale. There were also other advances that would aid their ability to care for wounded soldiers.

What kind of developments?

Number one was the availability of penicillin. Infection after wounds was a terrible problem in World War I and early World War II until penicillin became widely available in 1943.

The problem was that there were 200,000 men between the ages of 45 and 18 (many of whom were 16 and lied about their age to join the army) heading to Europe to liberate the women of Europe. So venereal disease became a widespread and debilitating problem for the Army, Navy, and Air Force. The penicillin dilemma was: do you take it to the battlefield or do you take it to the brothel?

There was great public relations poster effort throughout the country and on army bases throughout Europe to prevent venereal diseases because penicillin would have to be administered to wounded soldiers.

Were there any other changes to the way injuries were treated?

In World War I, a guy gets shot and you put him on a stretcher, and it's a long drive to the nearest hospital.

For World War II, the military developed the evacuation chain. It all started with a combat medic. That fueled a system that moved from a field hospital to a larger hospital to a general hospital and ultimately, if necessary, to evacuation to England. He saved many lives.

Were combat medics new to World War II?

The job existed before, but it was formalized. It was a very interesting nine month tour of duty in military service, tactical training and of course the medical aspect of assessing injuries, administering morphine, splinting and stopping bleeding. They had plasma transfusions available to withstand the shock.

Many of them were conscientious objectors. They were in basic training next to people who are going to carry a rifle and kill people. There was friction between the two until the moment someone got hurt and started yelling, “Doctor!”

What about the nurses?

Frances Payne Bolton She was a congresswoman from Ohio. She basically said, “The doctors are going to do this and that. What about the nurses? Then she passed by Bolton Act 1943who created the US Cadet Nurse Corps. It was essentially a GI Bill for nurses. This was a focused, fast-paced, and free program.

Before Pearl Harbor, there were only about 19,000 Army nurses. At the end of the war, if you combine the European theater with the Pacific theater, there were hundreds of thousands of nurses.

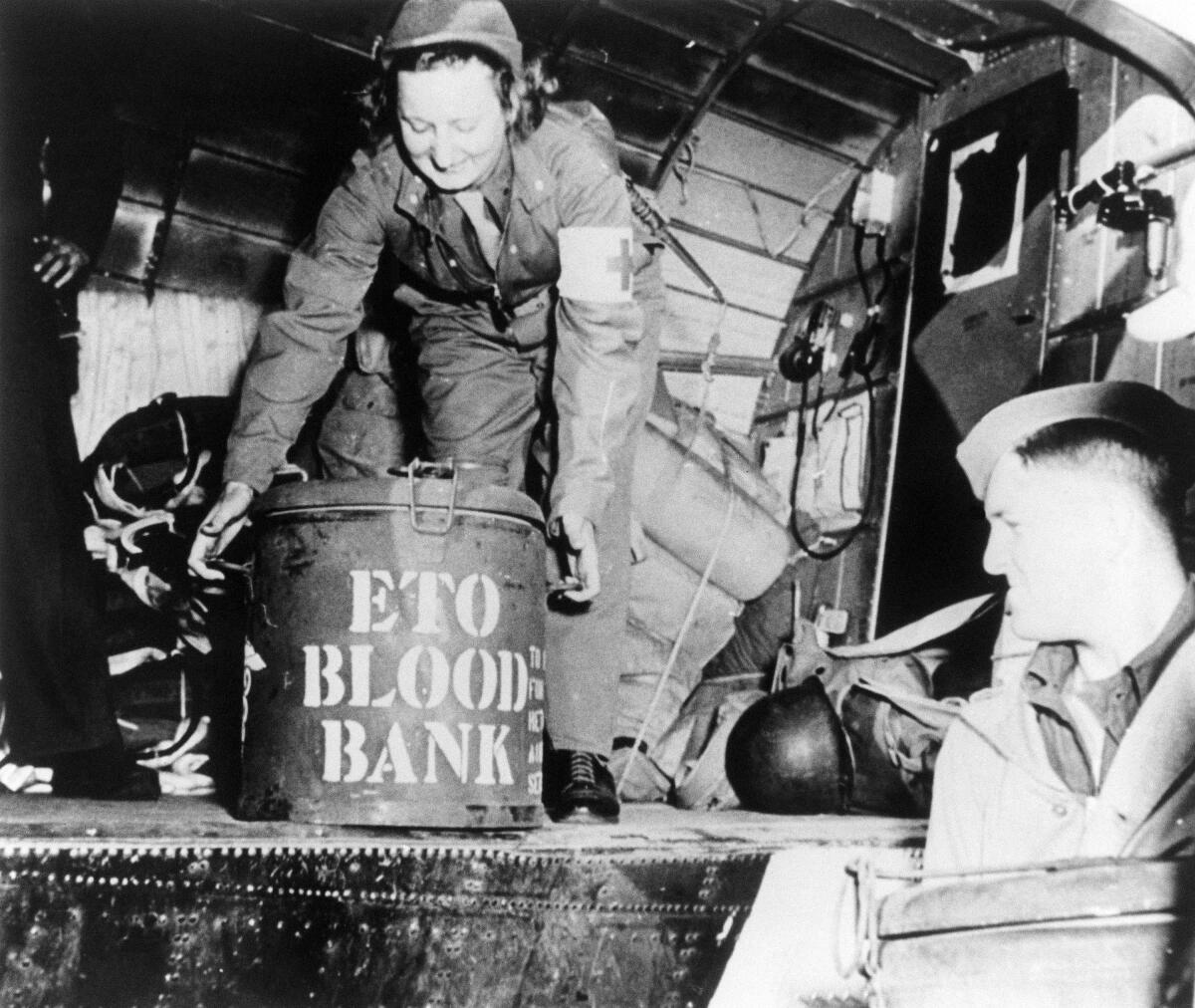

Lieutenant Stasia Pejko performs a last-minute check on blood bound for France on June 14, 1944.

(Associated Press)

What about other new roles?

This was the first time in the war that air evacuation was used extensively. This gave rise to the creation of the flight nurse, who had to take care of many things in addition to caring for a patient on the ground. They had to learn to survive accidents. They had to learn to deal with the effects of high altitude.

Did any of these innovations in health care return to the United States after the war?

The general theme in the history of military medicine is that once a war ended, there was very little interest in using that event for military progress, except in World War II.

The advances that emerged from World War II begin with penicillin. Number two was the treatment of thoracic, abdominal and vascular injuries.

Number three was the advances in the use of plasma and blood banks, particularly thanks to the work of Dr Charles Drew, which is a story in itself. Her contributions saved countless lives.

The fourth was the explosive growth of the Veterans Administration and VA hospitals. There were tens of thousands of people who served the country returning home, and the VA system would have to take care of them.

Number five was government involvement in Medical Investigation. Before World War II, it was unusual for the government to fund medical research.

And the sixth advance was the increase in knowledge about the neuropsychiatric effects of war. It started as battle fatigue and then evolved into shock. It later became post-traumatic stress disorder.

Has the American medical establishment achieved anything of this magnitude since World War II?

I'm no expert on military warfare, but now with drones, computers, and special operations, I can hardly imagine so many people heading to a beach in hand-to-hand combat.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.