Christopher Boyce and Andrew Daulton Lee were friends with childhood, altars raised in Catholic banks and prosperous suburbs of the green stick peninsula.

In the mid -1970s, Boyce was angry at the Vietnam and Watergate War. He was liberal, a Stoner and a hawk lover. Lee, a doctor's adoptive son, was a cocaine and heroine pusher who was spiral in addiction.

The way they became spies for the Soviet Union is an emblematic history of southern California of the seventies, where the enormous aerospace industry of the Cold War of the state collided with its anti-establishment youth currents.

Everyone agrees that it should never have been possible.

In the summer of 1974, Boyce, a brilliant but discontent university university, got a job as an employee in the TRW defense and space systems complex in Redondo Beach. He won incoming through the old and old network: his father, who directed security for a aircraft contractor and once was an FBI agent, had called for a favor.

In this series, Christopher Goffard reviews old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, the consistent to the dark, immersing himself in files and the memories of those who were there.

Boyce won $ 140 per week at the defense plant and maintained a bar attending the second job. TRW researchers had made only a superficial history verification. They jumped to their companions, who could have revealed their links with the culture of drugs and with Lee, which already had multiple drug busts and a serious cocaine habit, the white dust that would inspire his nickname.

In “The Falcon and The Snowman”, Robert Lindsey's story about the case, the author describes Boyce who starts the day bursting amphetamines and decreasing after a turn swelling an articulation in TRW parking. Falconry was his greatest passion. “Flying a hawk exactly in the same way that men had done centuries before Christ transplant Chris in his time,” Lindsey wrote.

Boyce impressed his bosses and was soon clear to enter the steel strength called the “black vault”, a classified sanctuary where he was exposed to sensitive CIA communications related to the United States spy satellite network. The satellites listened to Russian missiles and defense facilities. Among the objectives was to frustrate a surprise nuclear attack.

When reading the CIA Communiques, Boyce did not like what he saw. Among his other sins, he decided, the United States government was deceiving its Australian allies by hiding the satellite intelligence that had promised to share and end up in the country's elections.

“I simply disagree with all the direction of Western society,” Boyce told The Times many years later. He attributed his opportunity for “synchronicity” espionage, explaining: “How many children can a summer job work in an encrypted communications vault?”

Soon he made the “biggest and foolish decision” of his life. He told his friend Lee that they could sell government secrets to the Soviets. Lee spoke at the Soviet embassy in Mexico City, where the Russians fed him with caviar and bought documents classified with toast, “to peace.”

Lee KGB managers devised protocols. When I wanted to gather, I recorded an X to the street lamps at intersections designated around Mexico City.

For more than a year, thousands of classified documents flowed from the TRW complex to the Soviets, and sometimes Boyce contradict them in pots in pots. In return, he and Lee received an estimate of $ 70,000.

At parties, Lee showed his miniature Minox camera and boasted that he was involved in Spycraft. In January 1977, desperate for money to finance a heroin agreement, reduced the instructions of the KGB and seemed without prior notice outside the Soviet embassy. The Mexican police thought it seemed suspicious and arrested him.

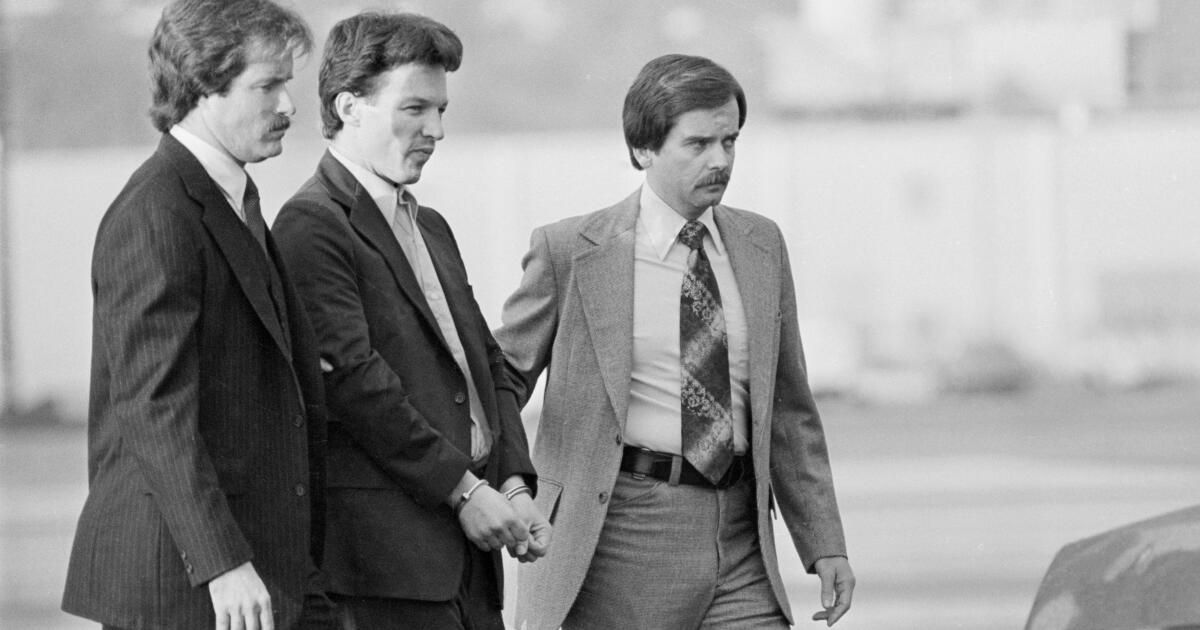

He held an envelope with filming that documented an American satellite project called Pyramider. Under interrogation, Lee revealed the name of his co-conspirator and childhood friend, who was also arrested. Boyce had just returned from a trip that caught the hawks in the mountains.

The espionage trials of the two men presented special challenges for the Office of the United States Prosecutor in Los Angeles. The Carter administration was ready to plug the case if that meant issuing too many secrets, but a strategy was devised: prosecutors would focus on Pyramider documents, which involved a system that never really came out on the ground.

Joel Levine, one of the US -attending prosecutors who prosecuted Boyce and Lee, said only a fraction of what they sold to the Soviets came out at the trial.

“They told me that these other projects should not be revealed. It is too expensive for our government, and a prosecution cannot be based on them in their entirety or partly,” Levine said in a recent interview. “You just have to stay away from that.”

For federal prosecutors in Los Angeles, hanging on the case was the memory of a recent humiliation: the collapse of the Pentagon Papers trial, as a result of the attempt of the Nixon administration to bribe the President Judge with a job. He had surprised prosecutors by surprise.

“We feared to ruin our reputation forever if it were something like that,” said Levine. “So we did it very, very clear from the beginning that if we smelled something like that, we would enter the courts and the case will dismiss us on our own.”

The defendants had very different reasons. Lee was for the money, said Richard Stilz, one of the prosecutors, in a recent interview. But “Boyce was totally ideology. He wanted to damage the United States government,” said Stilz. “I just hated this country, point.”

The defendants obtained separate evidence. A crack that had been growing between them deepened with their mutually hostile defenses. Lee defense: Boyce had led him to believe that he was working for the CIA, feeding the wrong information to the Russians. The jurors condemned Lee de Espionage, however, and a judge gave him a life term.

Boyce Defense: Lee had chanted him in the espionage threatening to expose a letter he had written, while drugged hashish, claiming the secret knowledge of the embezzlement of the CIA. The jurors also condemned Boyce, and a judge gave him 40 years.

In January 1980, in a federal prison in Lompoc, Boyce hid in a drainage pipe and ran to freedom over a fence. He was fleeing for 19 months. He stole Banks in the northwest of the Pacific until federal agents caught him out of a hamburger in the state of Washington.

He was convicted of bank robbery and obtained 28 years. In 1985, the same year a popular film adaptation of “The Falcon and the Snowman” was launched, Boyce testified in Capitol Hill about the despair that attended a spy life.

“There was no emotion,” he said. “There was only depression, and desperate slavery to an inhuman and inhuman foreign bureaucracy … no American who has gone to the KGB has not come to regret.”

He talked about the ease with which he had allowed access to the material classified in TRW. “Security was a joke,” he said, describing regular bacardi parties in the black vault. “We use the code destruction blender to make banana daiquiris and mai tais.”

Cait Mills was working as a legal assistant in San Diego when he read Lindsey's book and was fascinated by the case. He thought Lee had been unjustly defamed, and spent the next two decades fighting to win probation.

He received support letters from the prosecutors and the judgment judge that attests that Lee had advanced towards rehabilitation. He had taken classes in prison and became a dental technician. He won probation in 1998.

He directed his attention to the liberation of Boyce, with whom he fell in love. She wrote to the Russians and asked how much value there had been in TRW's stolen documents and received a fax claiming that it was useless. He left in 2002 and married. They later divorced but remain close. Both live in the center of Oregon.

Stilz maintains the damage to the United States was “huge.”

“In a case of murder, you have a victim and a person dies,” said Stilz. “In a case of espionage, the whole country is a victim. We were very advanced about Russians in spy satellite technology. They leveled the playing field. That is probably the most important point.”

It does not give credit to the statement of the Russian government that it did not obtain any value of the secret information. “Of course they would say that,” said Stilz. “What do you think they would say? 'Oh, yes, allowed us to catch up with the United States in terms of espionage.” They won't say that. “

Cait Mills Boyce said that Boyce and Lee, the best friends of childhood, no longer speak, and that the silence between them injured Boyce.

“He said: 'I love that man; I always loved him. He was my best friend.'

She said Boyce, now in her 70 years, lives a lonely life and immerses herself in the world of hectrería. “All his life, and does not joke, it's not hawk,” he said. “He will die with a hawk in the arm.”

Part of what pushed him into the world of espionage, he thinks, was the challenge. “I think his unusual intelligence led him along a capricious path that ended up being a disastrous path, not only for him but for all those involved,” he said.