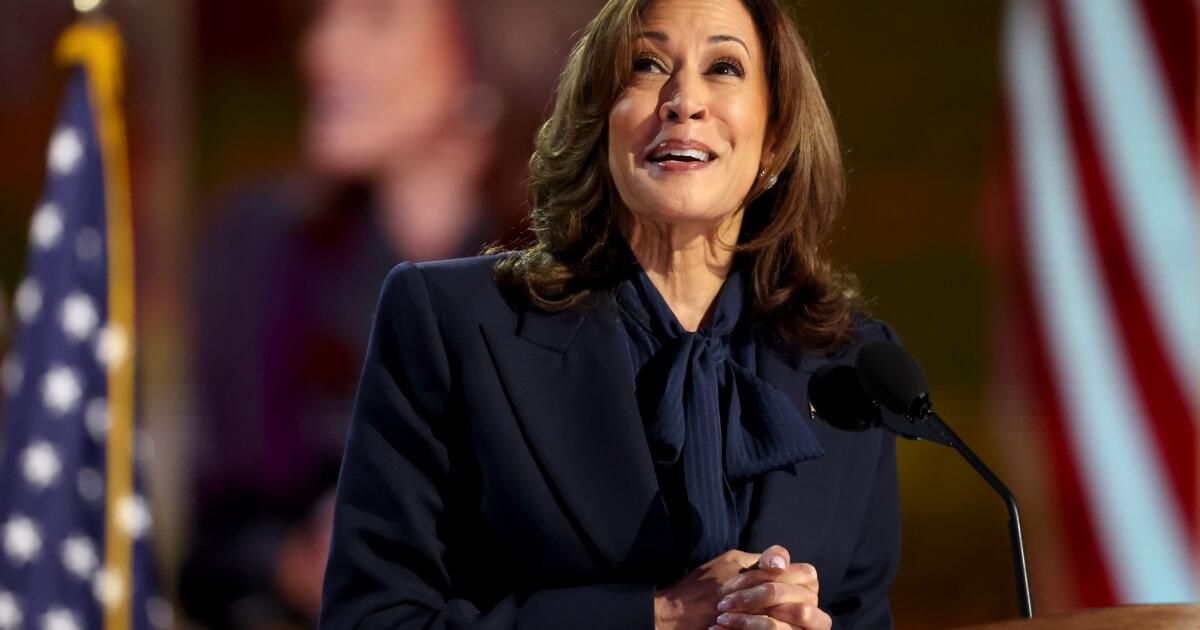

When Kamala Harris was formally installed as the Democratic presidential nominee, her home-state delegation had the best seats in the House, right up front.

Visions of the Golden State and a parade of its personalities filled the four-day convention program, and passes to the after-parties in California (featuring performances by John Legend, The Killers and Oakland's Tony! Toni! Toné) were among the hottest tickets in Chicago.

Suddenly, California is at the center of politics, in a way the nation's most important and populous state hasn't been since former Gov. Ronald Reagan was in the White House.

For the first time in history, a California Democrat leads the party's presidential ticket, thanks in large part to the machinations of another California Democrat who helped sideline the incumbent (and candidate-in-waiting).

“California is living through a momentous moment,” said Don Sipple, a political strategist who helped elect several California governors, thanks to “the woman who opened the door and the woman who walked through it.”

(Though, it should be noted, the woman who opens the doors, Nancy Pelosi, and Harris have never had a close relationship. The former House speaker spoke publicly of an “open process” to replace President Biden before endorsing his vice president as the best alternative after Biden dropped his reelection bid.)

With increased attention comes increased scrutiny, and with that added scrutiny comes a fight to define California — and, by extension, Harris — for the rest of America.

The result could very well determine who wins in November.

Is California an incubator of innovation and opportunity that continues to attract entrepreneurs and dreamers from around the world, as it has done for more than 150 years?

Or is it an overstretched and overextended collection of struggling communities that are failing to provide even the most basic things (safety, clean shelter and sustainable livelihoods) to a shamefully large portion of their population?

Yes and yes.

“There is a lot of evidence” to support both views, said Jack Pitney, a former Republican operative and professor of government at Claremont McKenna College, paraphrasing Walt Whitman.

“California is a big country. It contains multitudes,” Pitney said. “It’s possible for two things to be true at once.”

Red and blue America. Prosperous and decaying California. Two ways of seeing the same thing.

Bill Carrick, a longtime political adviser to the late Sen. Dianne Feinstein, scoffed at the idea that Harris' home state would hang like a millstone around the vice president's neck.

“Ultimately, a presidential campaign is about choosing someone who you think will make your life better,” said Carrick, who has worked extensively in national politics. It’s not, he said, about the candidate’s return address.

Of course, Carrick continued, “there are some ideological Republicans who are Trump devotees” and who enthusiastically embrace the narrative that California is hell, but “we’re not going to get them anyway.”

Most voters, or at least those who are open to supporting Harris, know very little about the vice president. That, Carrick said, gives her the opportunity to present herself (and her home state) on her own terms, “as opposed to the Republican Party’s cartoonish characterization.”

Maybe so.

But Trump and his fellow Republicans, with the help of Fox News and other like-minded media outlets, will argue that California is an example of what goes wrong when Democrats are in charge. They will hold up Harris, who has held statewide office for more than a dozen years, as the prime example of their destructive establishment.

That vastly overstates her power and influence, first as attorney general and then for a relatively brief period as one of California’s two U.S. senators. But that detail is sure to be lost in the fog of campaign warfare.

Harris is, however, an exemplar of his home state in one significant sense.

There is no doubt that it reflects the politics and makeup of modern California, just as the two presidents the state produced, Reagan and Richard M. Nixon, embodied the California of their time.

Both men came to power at a time when California was overwhelmingly white and Republican, with a marked conservative lean. When Harris arrived in Sacramento after being elected attorney general in 2010, the state was solidly Democratic, increasingly liberal and had more black and Latino residents than white ones. No less important, there were also many more opportunities for a woman in politics.

In this way, Harris and Reagan serve as perfect complements to the state they represented.

Given the changes over the past 30 years, it's surprising that California Democrats haven't managed to put one of their own in the White House, said Jim Newton, a state biographer and historian.

“We consider it an exceptionally blue place,” he said, “and it has produced many national Democratic leaders.”

They include the legendary and powerful Rep. Phillip Burton, Pelosi (who succeeded Burton’s widow as San Francisco’s representative in Congress) and Feinstein. But until Biden chose Harris as his running mate, no California Democrat had been even remotely close to the White House, though several tried.

Of course, Harris wouldn’t have had this chance at the presidency if not for a unique set of circumstances. If Biden hadn’t performed so terribly in that June debate, if Democrats hadn’t panicked afterward, if Pelosi and other party leaders hadn’t maneuvered to sideline the president, the vice president might very well have lost his job in January.

That could still happen, but you have to give Harris credit for getting where she is. After 20 years in politics, she is one step away from the White House and making geographic history.

In politics, as often in life, timing is everything.