It has become a painful pattern for Germany's political mainstream: Once again, a far-right party that for many evokes the country's Nazi past is poised for an unprecedented electoral show of strength.

The populist-nationalist Alternative for Germany (AfD) party — which in little more than a decade has grown from an openly anti-immigrant fringe movement to a rising force in local and national politics — is expected to do well or even come first in two state elections on Sunday in the former East Germany. A third vote in another eastern state is scheduled for late September.

If the AfD wins the largest share of the vote in either election, as public opinion polls suggest, it would mark the first such state-level victory for a German far-right party since World War II.

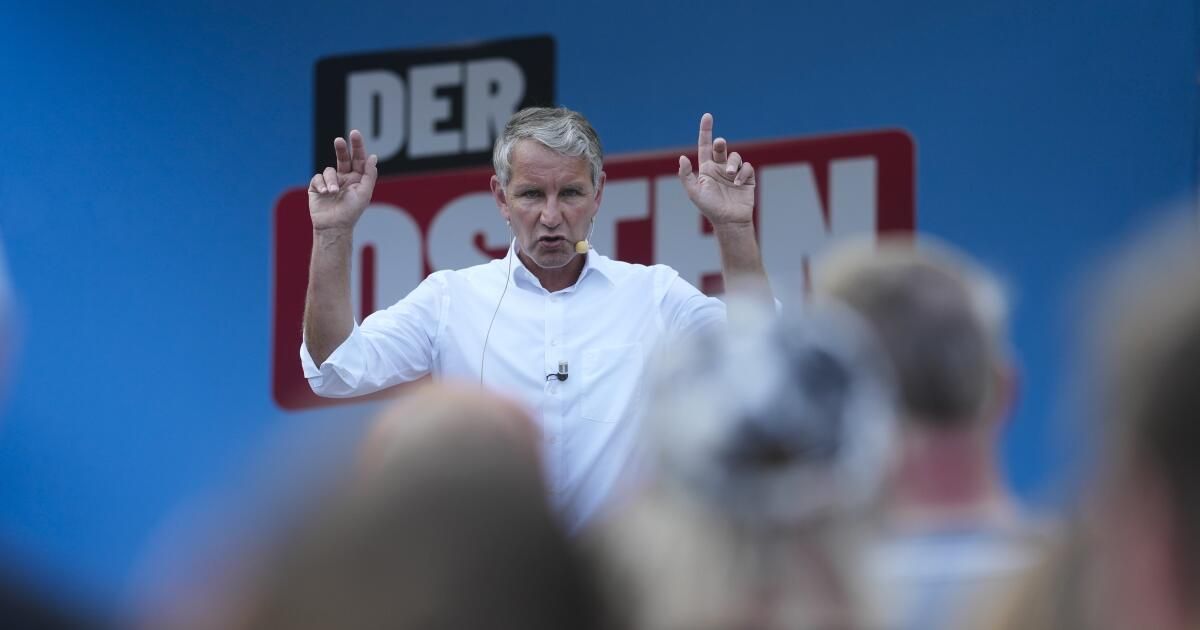

Bjoern Hoecke, leader of the far-right Alternative for Germany party in the state of Thuringia, poses for photos with a supporter during a rally in Apolda, eastern Germany, in August 2024.

(Jens Schleuter/AFP/Getty Images)

“It's definitely a dramatic change,” said Constantin Wurthmann, a professor of comparative politics at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, referring to the expected defeat of parties aligned with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz's ruling coalition.

Analysts say the AfD is likely to benefit from both the location and timing of the vote. The three states – Saxony and Thuringia, which vote on Sunday, and the rural state of Brandenburg surrounding Berlin, where the election will be held on September 22 – are in the heart of the country’s east, where the party enjoys its strongest support.

And just nine days before the first of those votes, tensions over immigration escalated dramatically due to a gruesome stabbing spree in which a Syrian man was charged.

Depending on the outcome, the trio of votes could be the second major blow to the AfD in Germany's political establishment this year. The party, which is under surveillance by the country's domestic intelligence agency for suspicions of extremism and anti-democratic tendencies, rose to second place in the country's European Parliament vote in June.

Although the vote was largely symbolic, as the European legislature wields relatively little power compared with the national parliaments of EU member states, it was seen as a wake-up call showing anger at centrist governments and traditional parties.

That anger crystallized in the Aug. 23 knife attack at a festival in the western city of Solingen that left three people dead and eight others injured. The 26-year-old suspect, who had entered the country as an asylum seeker, had been under a deportation order since last year.

And a claim by the extremist group Islamic State has raised fears of a possible new wave of terrorist attacks in Europe.

People lay flowers near the site of a deadly knife attack in Solingen, Germany, on August 23. Analysts say the attack is part of the far-right's anti-immigrant agenda; the suspect had entered the country as an asylum seeker.

(Henning Kaiser/Associated Press)

Analysts said the episode fit into the far-right agenda of portraying immigrants as dangerously violent and the government as complacent in the face of a potent threat, an echo of U.S. political discourse this presidential campaign season.

“I have the impression that the AfD will do better than expected after the Solingen attack,” said Sabine Volk, a political science researcher at the University of Passau.

Scholz's centre-left party supports the right to seek asylum, in contrast to the AfD, whose national leaders have called for a complete halt to all immigration, but the chancellor said after the Solingen attack that irregular migration must be more strictly controlled and deportations carried out more quickly when asylum applications are rejected.

Analysts predict that the immigration issue will continue to cause divisions.

“Established parties must address concerns about immigration or else the far right will… [parties] “We have a monopoly on them,” wrote Katja Hoyer, an author and academic from former communist East Germany, on the social platform X.

The upcoming elections highlight the persistent sense of political grievance and alienation in the east of the country, nearly 35 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. A recent survey by the German economic institute IW indicated that a fifth of easterners felt economically marginalised, even though financial statistics suggest their region has been closing the gap with the richer west.

This helps boost voter support for populist parties, whether far-right, such as the AfD, or far-left, such as the Reason and Justice party, known by its German acronym BSW, which is also expected to do very well in the upcoming state elections.

Even if it wins a majority in the next election, the AfD is unlikely to win a majority. It would need the support of one or more other parties to form a governing legislative coalition, but so far others have been reluctant to ally with it.

However, among party faithful, feelings of resentment persist (and grow).

“Many of the promises made to East Germans have not been kept,” says analyst Wurthmann. “And if you look at the influence of the Soviet era, some in the East have not fully accepted democratic values.”

German courts and law enforcement have cited precisely that — the undermining of democratic values, the use of hateful rhetoric — in formally designating the AfD as a suspected extremist organization.

Many Germans are shocked by the party's reintroduction, however indirectly, of banned expressions and symbols associated with the Nazi era.

In July, a German court found Bjoern Hoecke, the leader of the AfD in Thuringia, guilty of using a Nazi slogan. He uttered only part of the phrase in question — “Everything for Germany!” — but was found to have encouraged a crowd at a rally to complete it.

It was his second such offence and the penalty was a fine.