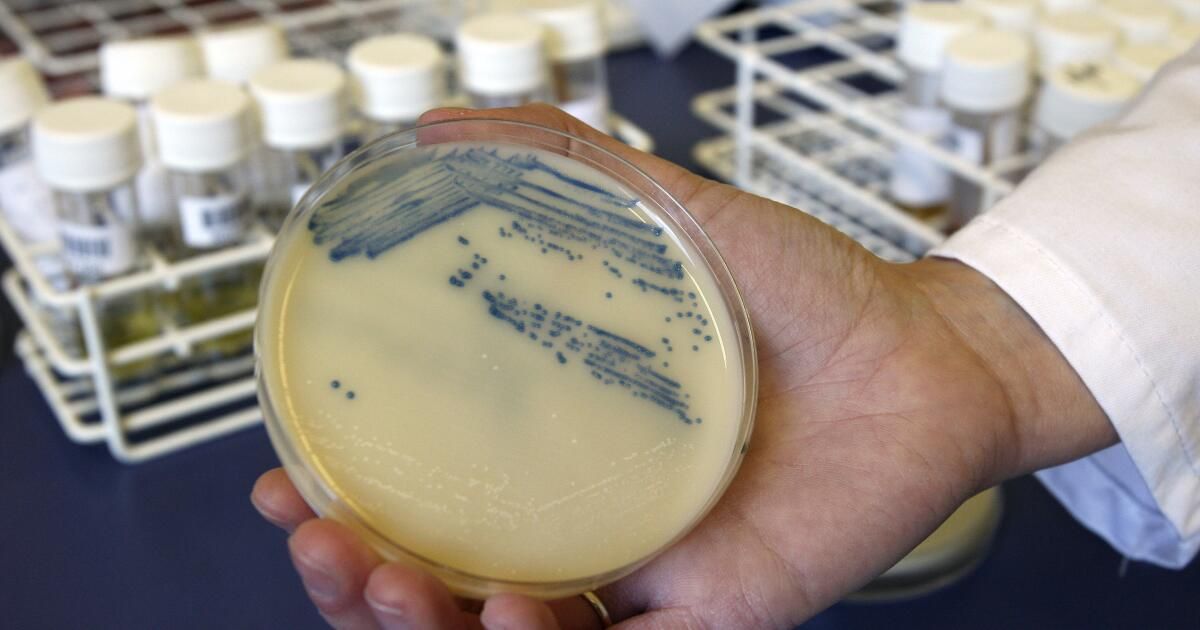

Since the dawn of the antibiotic era, opportunistic pathogens have evolved defenses faster than humans can develop drugs to combat them.

At the same time, humans have unwittingly given microbes an advantage by overusing antibiotics, allowing pathogens that survive exposure to pass on their resistant traits.

Now, A new report concludes that that unless officials take steps to develop new drugs, “superbug” infections could kill nearly 2 million people a year by 2050, a 67.5% increase from the 1.14 million lives lost this way in 2021.

According to a WHO study, 8.22 million more will die from causes related to these infections by 2050. Global research project on antimicrobial resistance published this week in the medical journal Lancet.

GRAM is a joint project of the University of Oxford and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington School of Medicine. The report is the most comprehensive assessment yet of the risk of antimicrobial resistance, or AMR, which the World Health Organization has long identified as one of the most Top 10 Threats to global public health.

It was released ahead of a United Nations General Assembly meeting later this month on drug-resistant pathogens.

“The figures in the Lancet paper represent a staggering and unacceptable level of human suffering,” said Henry Skinner, chief executive of the AMR Action Fund, a public-private partnership that invests in the development of new antibiotics, who was not involved in the study. “If governments continue to fail to meet their moral obligations to protect and care for their populations, as this paper demonstrates, they will condemn millions of people to unnecessary deaths.”

According to the report, about two-thirds of deaths from antimicrobial resistance in 2050 will occur among people aged 70 years or older. Older people are already at higher risk of contracting drug-resistant infections, which are often acquired in hospitals and care facilities.

Between 1990 and 2021, the report noted, ADR deaths increased by more than 80% among people aged 70 years and older.

The mortality rate from resistant pathogens is projected to be highest at all ages in South Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean.

The development of new antibiotics has been painfully slow, especially when compared with drugs with better financial incentives for producers. Vital as they are, antibiotics are not meant to be taken long-term like drugs for chronic diseases. The most potent ones should be used as sparingly as possible to give bacteria fewer opportunities to develop resistance.

In June, The World Health Organization warned There are currently very few new antibiotics in development worldwide, and those that exist are far from achieving the innovation needed to eliminate the most dangerous microbes.

Of the 32 antibiotics being developed against microbes on the WHO list List of priority bacterial pathogens for 2024According to the organization, only 12 of them adopted non-traditional methods, which is vital to prevent the rise of drug resistance. And of those 12, only four were active against the pathogens that the WHO identified as the most critical threat to public health.

The scenario painted in the GRAM report is grim, its authors noted, but not inevitable. Improvements in vaccine distribution and access to clean water and sanitation have helped halve deaths linked to antimicrobial resistance among children under five between 1990 and 2021, even as superbugs proliferated.

With improved infection control measures and accelerated drug development, the report says, up to 92 million lives could be saved between 2025 and 2050.

“The data shows that if we take action to achieve better management practices, improved access in low- and middle-income countries, and new investments to strengthen the antibiotic supply chain, we can save tens of millions of lives,” said James Anderson, president of the AMR Industry Alliance.