A Florida federal judge's dismissal Monday of a criminal case accusing former President Trump of illegally retaining classified documents after leaving office did not come out of the blue.

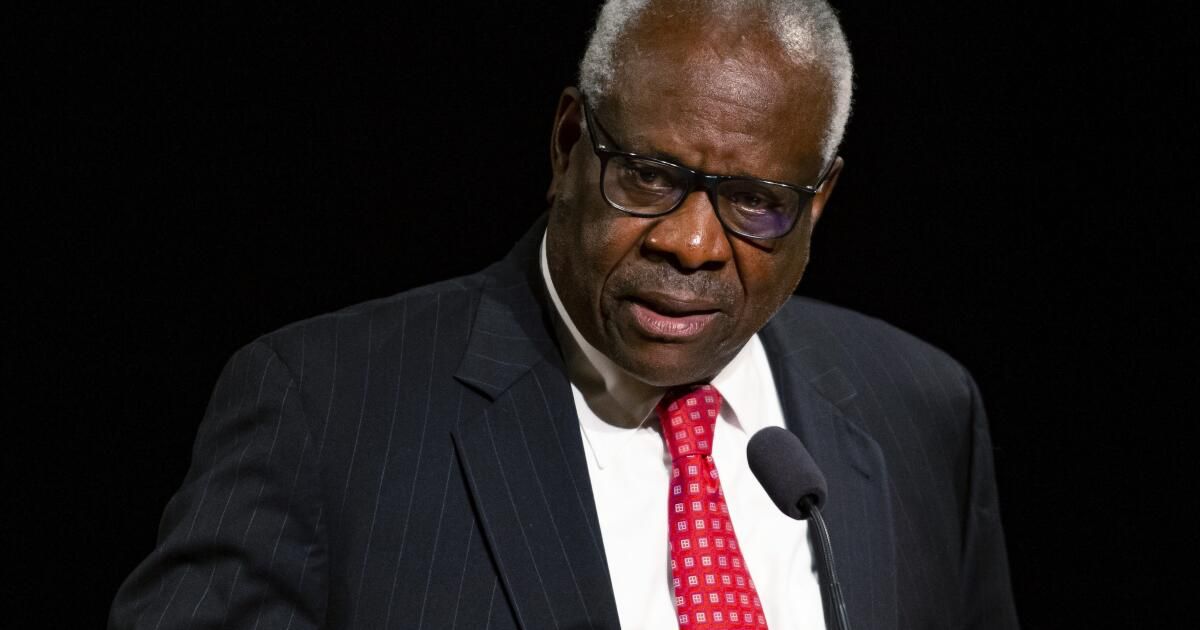

Two weeks ago, Justice Clarence Thomas called for a halt to federal proceedings against Trump on the grounds that the appointment of special prosecutor Jack Smith was unconstitutional.

“There are serious doubts as to whether the Attorney General has violated that structure. [of the Constitution] “By creating an office of special counsel that has not been established by law,” Thomas wrote earlier this month in a concurring opinion in the Trump v. United States case on presidential immunity. “Those questions must be answered before this process can proceed.”

Thomas spoke only for himself, but he gave voice to an argument that has gained traction on the right. The Supreme Court's conservative majority is skeptical of Smith's prosecution, so the justices could well agree that his appointment is unconstitutional if the matter reaches the Supreme Court.

And now it has prompted U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon in Florida to throw out a case accusing Trump of mishandling classified documents.

The Supreme Court dealt a major blow to the Justice Department’s prosecution of Trump when it ruled earlier this month that the former president — and all future and former presidents — have broad immunity from criminal charges for official acts performed while in office.

The separate challenge to the special counsel's appointment could unravel what remains of the prosecutions against Trump.

This is a problem that does not have a good solution in the Constitution.

The Justice Department, which is part of the executive branch, has the power to prosecute violations of criminal laws. But how does it proceed if the president may have violated criminal laws?

Fifty years ago, when the Watergate scandal broke, President Nixon's attorney general, Elliot Richardson, appointed Harvard Law professor Archibald Cox as special prosecutor. Cox led the Watergate investigation, which Nixon did not question, at least at first.

The Supreme Court cited that appointment with apparent approval in the 1974 Nixon tapes case, but Cannon noted in his ruling that it was not part of the formal ruling.

After Watergate, Congress passed a new law authorizing a panel of judges to appoint independent prosecutors to investigate allegations involving the president or his top aides and appointees. The Supreme Court upheld that authority in 1988, over a fierce dissent by the late Justice Antonin Scalia.

But that system was roundly condemned by Republicans and Democrats because it led to endless investigations involving presidents including Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton. Congress allowed the law to expire after Clinton left office.

When Trump became president, the Justice Department — much to Trump’s frustration — returned to an earlier era and decided to appoint special prosecutors to conduct sensitive investigations.

Robert Mueller, a highly respected former FBI director, was appointed to investigate alleged links between the Trump campaign and Russian interference in the 2016 election.

Two years after the Biden administration took office, Attorney General Merrick Garland appointed Jack Smith, a highly aggressive prosecutor, to investigate criminal allegations against Trump.

Garland said he chose a special prosecutor because that person could act independently of the Justice Department, which was controlled by a Democratic president running against Trump.

But that argument did not appease conservatives, who pointed out that Smith was not a congressionally confirmed federal prosecutor and did not hold a senior position in the Justice Department created by Congress.

Thomas highlighted those arguments.

“That the office of special counsel was ‘established by law’ is not an insignificant technicality,” he wrote. “If Congress has not reached consensus on the existence of a particular office, the executive lacks the power to unilaterally create and then fill that office.”

Trump's lawyers had cited Thomas' opinion as grounds for dismissing the special counsel's case in Florida.

In response, Smith described Thomas’ opinion as a “single-justice concurrence” that does not “bind this court” and ignores the history of judges allowing special prosecutors.

But in her opinion Monday, Judge Cannon described the special counsel as a private citizen who wielded the vast prosecutorial power of the U.S. government. Concurring with Thomas, she said it was neither a position created by Congress nor a position specifically authorized by law.

The special counsel can appeal her ruling to the conservative 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta.

Trump's lawyers are also likely to cite it when U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan in Washington reconsiders what remains of the special counsel's case accusing the former president of conspiring to subvert the 2020 election.